CONTENTS

To Christine,

who made this book possible

FOREWORD

D AN Rattiner has lived in the Hamptons even longer than I have. Its forty-four years for me now, although on the ocean in Montauk, which many of us who live there do not consider to be a part of the Hamptons. Montauk, as Dan succinctly points out, is of an independent turn of mind, and while the McMansions are starting to turn up here and there, Montauk manages to retain much of what endeared it to Dan and me so long ago.

While Dans book evokes the changes that have threatened what those of us who have been here a long while love and treasure about the Hamptons, it is, in the main, a long love poem to the area and the extraordinary people who have occupied it and, more often than not, helped to preserve its character.

Dan is, front and center, a journalistand a damn good oneand this book, a journal of a place and its people, is wonderful reading. In its pages Ive learned a lot I didnt know and met a lot of people I wish I had.

If I write here that I cannot imagine a chronicle more inclusive and revealing, fascinating and objective, yet for the greater part affectionate, I am not piling it on too thick. This book is damn good work.

S OME addenda.

I wish I had known Dan while he was writing his piece on Nixons stays at Gurneys Inn in Montauk. My house, looking down on the beach, is not far from that spot and, one day, I was looking over my gradual cliff and I saw an extraordinary sight: There was a man in a suit and tie and shoes walking the beach among the sunbathers, shaking hands with those who were willing to have their hands shook. Five paces behind him were two other men, similarly dressed but with their right arms extended and covered with beach towels. It is so clear to me now: There was Nixon and there were his bodyguards with guns. The mind boggles: What if Id been gifted with insight into the future and what if Id been, by nature, a killer. Just think what I could have saved the country, from my perch on my cliff!

I have one quarrel with Dans pungent writing about the disaster that was Sag Harbor in the 1960s, and it concerns his appraisal of John Steinbeck who was, I must state here, a close friend of mine, though we disagreed politically very frequently.

In his quoting of Johns letter outlining his theoretical invention of more efficient killing weapons for the Vietnam War, Dan fails to understand the deep and awful humor that motivated the suggestions. John wouldnt have hurt a fly, and I read in his advice the subtext Well, I disapprove of this brutal and wrongheaded war, but, if you want to do it in a really effective brutal and wrongheaded way

Sorry, Dan; I cant let you have that one the way you saw it. Friendship can blind us, though, and while I doubt it, you may be right.

A minor quarrel, I guess, with a book I feel anyone who wants to fully understand the Hamptons must read.

EDWARD ALBEE

New York City, 2007

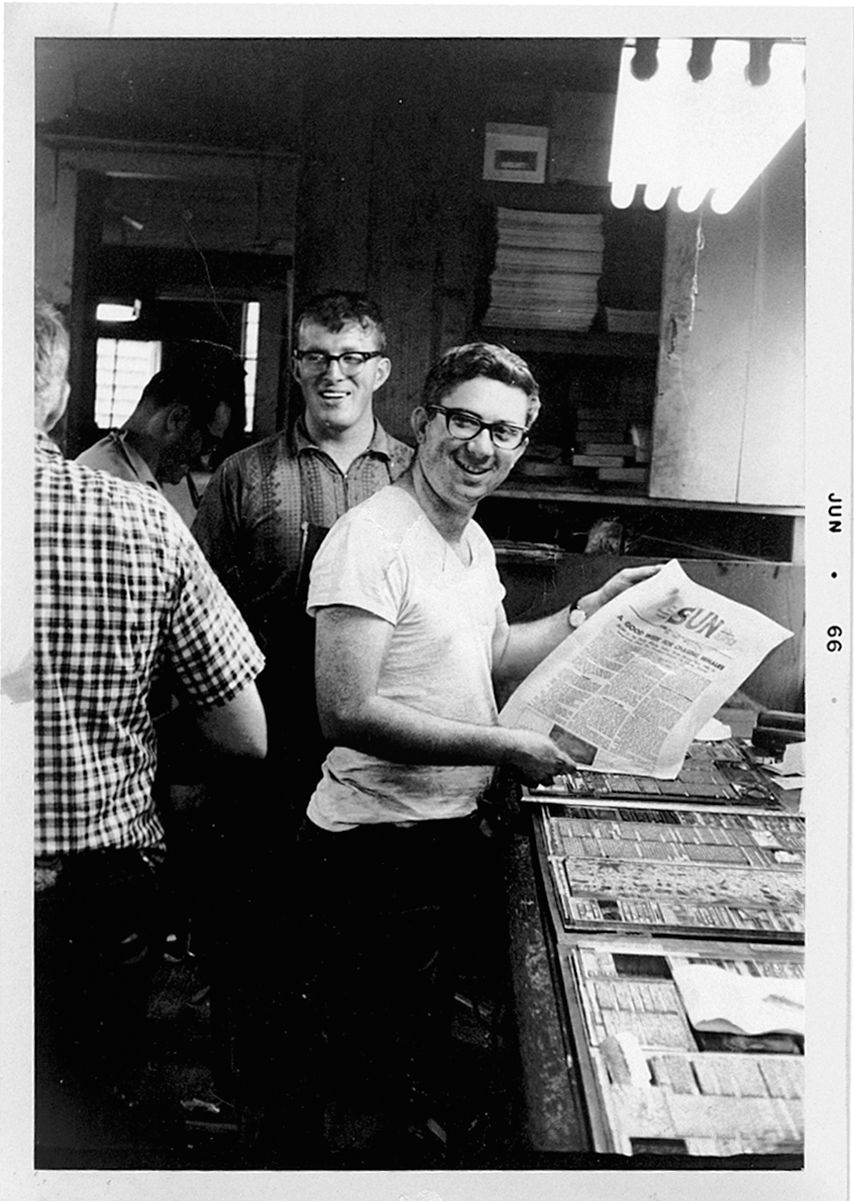

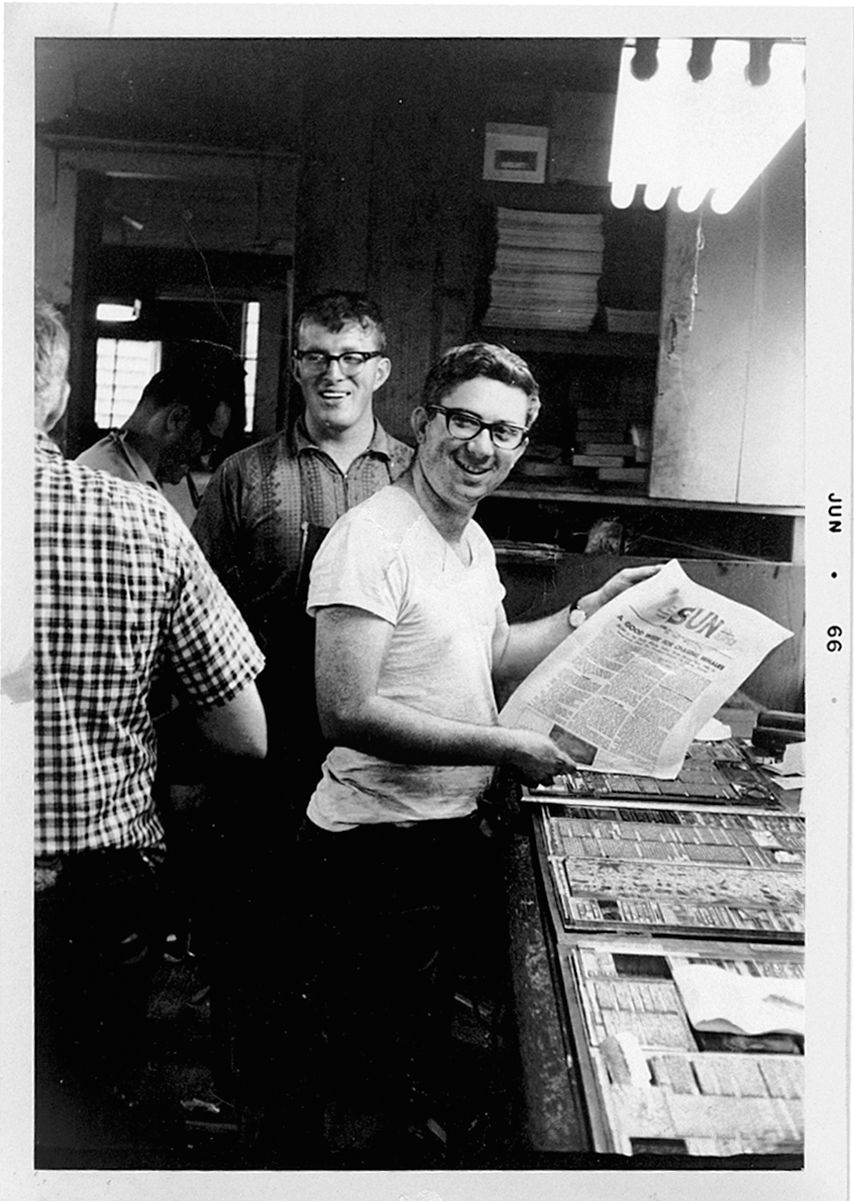

At the Print Shop

A T 4:00 A.M. on a warm summer night in 1960, filthy with sweat and black printers ink, I wandered out the front door of the Suffolk County News in Sayville, Long Island, in search of a place to lie down. There wasnt any. Overhead, the streetlights in front of the stores glowed. A hot wind rustled the leaves of the oak trees. All was quiet.

Where could I lie down? My car was right there, parked in front of the print shop, but I couldnt stretch out fully in that. Behind me, inside the building I had just come out of, were several dark front roomsan editorial office, a business office, an advertising office, a lobby and counterbut none had a couch or even a comfortable chair. Behind those rooms was the big open space that housed the print shop. Fluorescent lights lit the room at that hour. Men bustled around. No place to lie down there either. Id have to look elsewhere.

I liked Sayville. It is, and was then, a small town halfway between Manhattan and Montauk quite similar to the one where I had grown up in New Jersey. Record stores and dress shops, a Woolworths and a mens shop, even three ice cream parlors lined the main street. But at 4:00 A.M. they were all closed. Even the all-night diner was closed. There was just nobody around.

WITH BOB SR. AND BOB JR. AT THE PRINT SHOP. (Photograph by Jim Lytton; courtesy of Dans Papers)

I had seen a park in back of Main Street and so I wandered down an alley along the side of the little Suffolk County News building toward it. It was a city block in size, and there were rows and rows of oak trees, bordering a gravel path that meandered down one side of the park and up the other. It was also dimly lit, by just four streetlights at the corners. Perhaps I could find a spot off somewhere in the dark where a tree provided some shadows. Or maybe there was a park bench. I looked for one. But there wasnt one. And so I retreated to a dark patch under a tree, sat down on the ground, noticed I was sitting on acorns that were quite hard, brushed them away with my hand and then lay down on the grass, got myself comfortable, and began to drift off to sleep.

H ERE is how my little weekly newspaper in Montauk was prepared for printing in 1960: It was almost exactly as Gutenberg printed things some five hundred years earlier. There were iron frames, much like picture frames, that had interior dimensions exactly the size of the newspaper page. You laid these frames on a stone counter, and into them you loosely assembled thousands and thousands of little pieces of lead type, each one a backward letter of the alphabet, or a backward word or series of words. The largest pieces, the headlines, were made of individual blocks of wood, each bearing one raised letter, made of a piece of zinc glued on the top. When the frames got filled up with all these letters in just the order you wanted them, you locked them in place by inserting an iron key into a slot and twisting clockwise a quarter of a turn. The frames ratcheted inward as you turned the key. The letters were thus pressed tightly against one another.

Then you got a piece of steel about the size and shape of a cookie sheet and slid it between the counter and the frame. With this in place to keep the little letters from falling out if they were not in quite as tight as they should be, youd pick the whole thing up and walk it to the pressroom, where youd slide it onto a shelf inside a twelve-foot-long flatbed press. Then youd slide out the cookie sheet, lock the frame onto the press, bring over all the other frames in this manner, put ink into a trough, and press a button to turn the press on.

In the early days of printing, you wouldnt press a button. Youd turn a crank. And the gears and the levers and the rollers of the press would move. In a three-step operation, a rubber roller would slide over a trough with ink in it, get inked, and then roll across the frames, wetting the letters. After that, a piece of paper would slide down gently onto the frames, and the clean rollers would roll the paper hard against the frames, transferring the ink from the letters to the paper. When the operation was over, a lever would peel the paper off the frames and there would be all the words, all black and shiny. Youd set the paper down to dry briefly, a metal folder lever would fold it, and there it would be, one page of a newspaper.

Next page