For Judy, my wife and best friend

Contents

I always said that I would not write another book. The danger of using the written word is that it can so easily be misinterpreted, which sometimes means that an idea put down on paper with the best intentions can be a trap for the unwary. You cannot train a dog by reading a book; nor can you modify a dogs behaviour by merely reading words on a page. When you, dear reader, cast your eyes over the words that I write you cannot feel the emotions that lay behind my words or see the images in my mind. So you must not view this book as a manual on how to raise, train or modify your dogs behaviour. You should view it as a philosophy of thoughts and emotions that may better help you understand your dog, as a way of bridging the sometimes immense and widening gap between man and dog.

In an age of technology, where it is possible to communicate almost instantly with someone on the other side of the world, we humans seem not only to find it more difficult to communicate with one another on an emotional level but we are also losing the ability to communicate with our canine friends. The world we live in bears little resemblance to the world our forebears lived and worked in, and gone are the days when dogs lived a life with freedom to exercise most of their natural behaviours. The role of the working dog has changed little but now there are fewer jobs to go around and many of the breeds born to do a job now find themselves in the almost impossible position of having to adapt to a life in permanent retirement. Even the humble family pet is rapidly becoming a thing of the past as our busy lives leave precious little time for family life. We are able to get things done now with the push of a button on a computer but we are losing our ability to understand the animals that we share our lives with, even at the most basic level.

Today we have more trained behaviourists than ever before, more professional dog trainers and more pharmaceutical companies have realised there are profits to be made by giving dogs mind-altering drugs. Yet dog behaviour in general is now rapidly getting worse just ask anyone who works in a rescue centre. Culturally, we are losing our rights to exercise our dogs off-lead in public leisure areas. We are also slowly but surely segregating dogs from children and it is sad that many children in the not too distant future will only ever see dogs in a segregated dog park. Do we really want our children, the next generation of dog owners, to grow up only being able to see a nicely trained dog within the confines of a dog-training facility or in an obedience ring? The days of dogs enjoying a day out with their families are numbered as more and more legislation is brought in by more and more countries to restrict ownership (banning breeds) and reduce the opportunities for good physical and emotional exercise in public areas.

Why is this happening? Because we are failing to understand, communicate with and train our family pets. Guide dogs are allowed access to public areas because they are well-trained and have to pass tests of outstanding social behaviour, not because they are necessarily any healthier or cleaner than our family companion. I have eaten in restaurants in Belgium and France where it is not uncommon to see a family enjoying a meal with their pet beside them at the table. This sight is very rare indeed in countries like Great Britain and the USA. There are also huge cultural differences in not only the attitude of dog owners but also in the behaviour of their dogs. Basically, if you look at any culture in the world, the behaviour of pet dogs is mirrored in the behaviour of its children. Why? Because they have the same role models for the way they behave.

Ask any breeder and they will tell you they can tell how a puppy will grow up based on the parents that want to buy it and the way their children behave when they come to view the puppy.

Take England as an example. England is a very small country, so if there is a change in the behaviour of a population then it will be more noticeable. In England, we have a tradition of companion dog ownership. When I was growing up in London, all my school friends had a dog. Where did these companion dogs come from? Generally, the puppies were bred in someones home and advertised in the local area.

Thus even before a puppy arrived in its new home, it would have built up a model of the world at the breeders that was not too dissimilar to what its life would be like when it went to its new family. Then we had the first change in culture. Prompted by animal charities and, I might add, professional breeders, the government decided to bring in the Breeding of Dogs Act 1973. This required breeders to obtain a licence from their local authority. Because the law was hastily drafted, it contained almost word for word the licence requirements for a boarding kennel! This started to signal the death knell for the pet dog breeder and, to the delight of puppy farms, large-scale dog breeding started to take place where emphasis was placed on breeds and marketing. Dog-breeding became, and has remained, big business.

But there is a way of changing attitudes in any culture by presenting good role models for behaviour. It starts with every dog trainer, behaviourist, groomer, breeder, dog sport enthusiast and companion dog owner understanding their responsibilities towards their community by learning how to communicate with and train their dogs. It requires everyone involved with dogs to understand that if breeders get it wrong, we all pay the penalty.

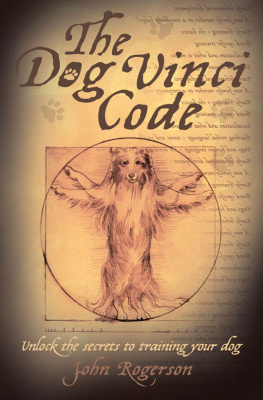

The Dog Vinci Code aims to get everyone back on track, the way it used to be: breeders producing nicer pet dogs, trainers learning the practical training skills by working with dogs rather than sitting in a classroom listening to a lecture on dog-training, and owners able to communicate with their dogs by understanding the almost forgotten code.

The art of raising and training a family pet is rapidly being turned into a science where the student is required to learn a new and complex vocabulary. Many of the people involved in this new science seem to understand more about statistical analysis than the emotions involved in raising a well-behaved pet dog. The emotional relationship that leads to a once-abandoned dog eventually becoming the ears of a deaf person cannot be defined by any scientific formulae. The mechanism by which a dog would willingly place its own life at risk in order to protect the life of its handler defies scientific analysis.

Next page