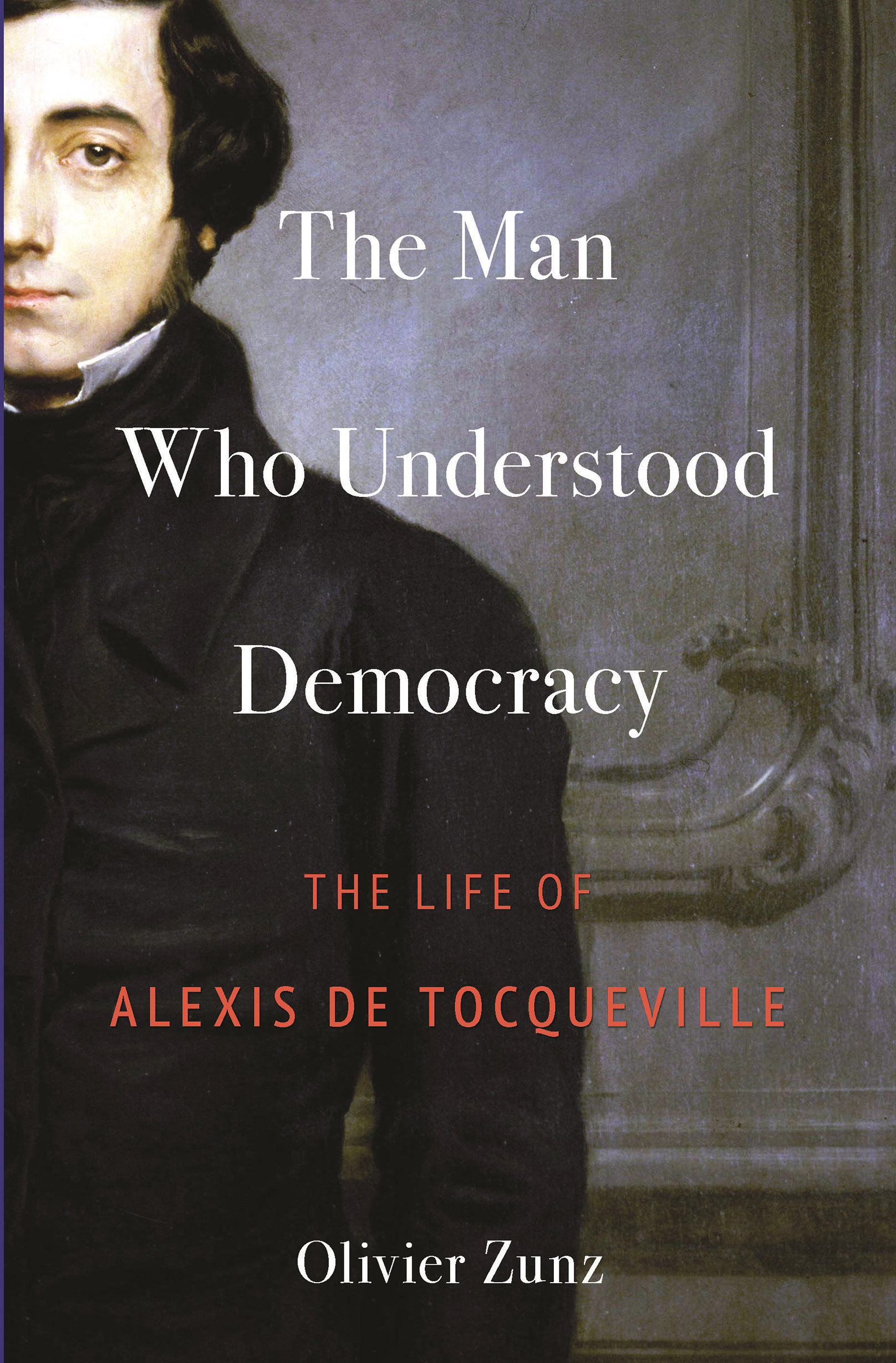

The Man Who Understood Democracy

The Man Who Understood Democracy

THE LIFE OF

ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE

Olivier Zunz

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zunz, Olivier, author.

Title: The man who understood democracy : the life of Alexis de Tocqueville / Olivier Zunz.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021041198 (print) | LCCN 2021041199 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691173979 (hardback) | ISBN 9780691235455 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tocqueville, Alexis de, 18051859Political and social views. | Aristocracy (Social class)France. | DemocracyPhilosophy. | Political scientistsFranceBiography. | Political scientistsUnited StatesBiography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Philosophers | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Ideologies / Democracy

Classification: LCC JC229.T8 Z86 2022 (print) | LCC JC229.T8 (ebook) | DDC 306.2092 [B]dc23/eng/20211128

LC record available at https: / /lccn.loc.gov/2021041198

LC ebook record available at https: / /lccn.loc.gov/2021041199

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Priya Nelson, Barbara Shi

Jacket Design: Pamela L. Schnitter

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: James Schneider, Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Joyce Li

Jacket image: Alexis Charles Henri Clrel, comte de Tocqueville (18051859). CPA Media Pte Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

To the memory of my friend Michel de Certeau (192586), who taught me that lhistoire nest jamais sre.

CONTENTS

Prologue

IS IT ANY WONDER that titles should fall in France? Is it not a greater wonder that they should be kept up anywhere? What are they? When we think or speak of a Judge or a General, we associate with it the ideas of office and character; we think of gravity in one and bravery in the other; but for a Duke or a Count, one cannot say whether these words mean strength or weakness, wisdom or folly, a child or a man, or the rider or the horse. So wrote Thomas Paine in 1791 during the French Revolution.

The measure of any form of government, Tocqueville believed, was liberty and equality. In an aristocracy, only privileged aristocrats could enjoy libertyat the expense of the liberty of others. In Tocquevilles democracy, by contrast, all citizens have the liberty to act within an agreed-upon legal framework. Tocqueville viewed equality as the engine of liberty, and although he recognized the need to repair social injustice, he saw equality not as a means of leveling but of uplifting. He believed that the pursuits of liberty and equality were intimately linked; he even imagined an extreme point at which liberty and equality touch and become one.

The transformation from aristocracy to democracy was not without its costs, either for Tocqueville or society at large. Tocquevilles own family was decimated during the Revolutionary Terror that engulfed France between 1793 and 1794. Tocquevilles parents, Herv de Tocqueville and Louise-Madeleine Le Peletier de Rosanbo, married in March 1793, only two months after Louis XVI had been beheaded. This alliance between a young army officer from Normandy, born to an ancient family of the military nobility (the nobility of the sword), and the daughter of a family that had risen through the highest echelons of royal administration (the so-called grande robe) might have fueled controversy only a few years earlier. But the wedding took place when the time for negotiating rivalries between different castes of French nobles was gone. Every noble in France was now suspected of conspiring against the Revolutiona crime whose penalty was death.

The brides father, the marquis de Rosanbo, was an important man before the Revolution. He was a principal magistrate of the highest appeals court of the time, prsident mortier of the parlement in Paris. The brides grandfather, Chrtien-Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, was even more important. As director of the book trade (la librairie) under Louis XV, Malesherbes had protected the philosophes, and as Louis XVIs minister he had promoted liberal reforms. He was one of two lawyers who defended the king at his revolutionary trial. Tocqueville admired his great-grandfather (whom he called his grandfather) for having pleaded the cause of liberty, a principle so dear to him, in the court of his no-less beloved royalty, and for having advocated for equality of rights despite being among those already privileged. But Malesherbess liberal views secured his family no protection.

The revolutionaries arrested all the adult members of the Malesherbes-Rosanbo-Tocqueville familyten in totalat the chteau of Malesherbes in the Loiret over the course of a few days in December 1793, transporting them to various jails in Paris to await summary trial and execution. Alexiss maternal grandfather, Rosanbo, was first to be guillotined, on April 20. Two days later, on April 22, his grandmother, Marguerite, went to the scaffold, followed by Aline-Thrse de Rosanbo, his aunt, and her husband, Jean-Baptiste de Chateaubriand (older brother of the great Romantic writer). Malesherbes was beheaded last on that day, after the executioners made him watch his daughter and grandchildrens heads fall from the guillotine in front of him.

The remaining family membersTocquevilles parents, Aunt Guillemette and her husband, Charles Le Peletier dAunay, and Uncle Louis Le Peletier de Rosanbowere in jail awaiting their turn when Robespierres own fall and execution on 10 Thermidor Year II of the French First Republic (July 27, 1794) put an end to the slaughter. They remained imprisoned for another three months before finally being freed in October.

Louise-Madeleine, already prone to depression in her youth, never recovered her sense of well-being. Tocquevilles parents spent ten months of the first eighteen months of their married life in jail. They mourned the execution of their closest family, and on release, they found themselves caring for the survivors. On the day Jean-Baptiste de Chateaubriand was taken from prison to the guillotine, Herv de Tocqueville promised him that, should he himself survive the Terror, he would adopt his brother-in-laws two young sons, Christian and Geoffroy, the only family members still in hiding at Malesherbes.

Eleven years later, in 1805, Louise-Madeleine gave birth to Alexis, her third biological child. She was disappointed that the baby was yet another boy, so keen had been her hopes for a daughter. Her husband attempted to console her with an optimistic prediction. Herv recalled in his Mmoires that on first sight of the baby, he thought, This child was born with so singularly expressive a figure that I told his mother he would become a man of distinction, adding with a laugh that he could one day become Emperor. The first half of his prophecy came to pass. The boy would enter the canon of great political philosophers. But far from becoming an emperor, he would dedicate his life to ending despotism.