Brandeis University Press

2022 by Bruce Davis

All rights reserved

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Brandeis University Press, 415 South Street, Waltham MA 02453, or visit brandeisuniversitypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Davis, Bruce (Former Executive Director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences), 1943 author.

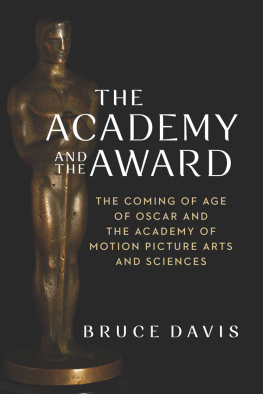

The Academy and the award : the coming of age of Oscar and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences / Bruce Davis.

Waltham, Massachusetts : Brandeis University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: The early history of the formation of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and its most famous awardthe Oscaras told by its former executive director who reveals many previously unknown storiesProvided by publisher.

LCCN 2022018487 | ISBN 9781684581191 (cloth) | ISBN 9781684581207 (ebook)

LCSH: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sci encesHistory. | Academy Awards (Motion pictures)History. | Motion picturesUnited StatesHistory.

LCC PN1993.5.U6 D285 2022 | DDC 791.43079dc23/eng/20220502

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022018487

Academy Award(s) and Oscars are registered trademarks and service marks of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The Award of Merit (Oscar) statuette is copyright 1941 by the Academy. The depiction of the Oscar statuette is also a registered trademark and service mark of the Academy.

Designed by Lisa Diercks / Endpaper Studio

Typeset in Rossanova and Mercury Text

Manufactured in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

ON THE FRONT JACKET: 1928 test casting of the Academy Award

For Jo, of course.

Following the fifth meeting of the Academys Board, on April 29, 1927, the directors (soon to be re-designated as governors) sat for a flashlight photo at their offices at 6912 Hollywood Boulevard.

BACK ROW, FROM LEFT: Cedric Gibbons (art director), J. A. Ball (cinematographer/color technologist), Carey Wilson (screenwriter), George Cohen and Edwin Loeb (legal counsel), Fred Beetson (MPPDA secretary), Frank Lloyd (director), Roy Pomeroy (effects technician), John M. Stahl (director/producer), Henry Rapf (producer).

FIRST ROW: L. B. Mayer (executive), Conrad Nagel (actor), Mary Pickford (actress), Academy President Douglas Fairbanks (actor), Secretary Frank Woods (screenwriter), Treasurer M. C. Levee (executive), Joseph M. Schenck (executive), and Vice President Fred Niblo (director).

INTRODUCTION

FOR ALL OF THE NEAR-FANATIC ATTENTION BROUGHT TO BEAR each spring on the Academy Awards, the organization that dispenses those awardsthe Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Scienceshas never been well understood. A lively interest has developed over the most recent decade in the organizations makeup in terms of age, gender, and racetheres no shortage of that kind of dataand of course the Awards decisions the Academy renders remain the subject of wide and warm debate.

But anyone looking for information about the history and objectives of the Academy, particularly in its crucial formative years, may have been surprised to find how hard that is to unearth. The organization itself has never produced a thorough account of its birth and its touch-and-go adolescence, and the few reports on those periods from outside have always had a glancing, cursory quality, as though no one had seen much value in taking a close look at how one of the best-known organizations in the world had grown to be that.

The emergence of the Academy in the late 1920s, and its struggle with the sequence of difficulties that prevented it from thrivingeven after its awards had become world famousis an intriguing story in itself. And the narrative gains weight from the fact that the men and women shaping the organizations early choices are among the motion pictures most significant figures to that point. The story of the Academys birth and maturation is a critical piece of Hollywoods history.

Part of the reason that the organizations early history isnt better known is that the Academy has preferred to keep many of its key written records unavailable to researchers. This is not to suggest aSkull and Boneslike obsession with secrecy, but just as the organization has always felt that it is enough to reveal the top vote-getters for an awardresisting all coaxing for the pulpy details of who finished second, or fifththe Academy has also tended to keep to itself the process of arriving at most other decisions. The eventual consensus is made public, but the records of the deliberation are consigned to its archives. Significant swaths of Hollywood history have never been known outside the boardroom.

Since the focus here is primarily on the first three decades of Academy history, it doesnt seem indiscreet at this point to release a few organizational cats from their bags. I retired from the Academy in 2011, after thirty years on its staff. I had been the organizations executive director for a shade more than twenty of those years, and I left persuaded that it was time that someone provided the Academy (and anyone else interested) with some of those lost details of its formative years.

I was aware, from my conversations over the decades with members, that almost no one in the organization claimed more than a blurry set of impressions about why the organization came into being and what sort of concerns had shaped it. This project taught me that I had no reason to feel superior. Large, embarrassing quantities of the information in this book were completely new to me whenwith the slightly wary, but much-appreciated blessing of the Academy officersI began wading into the formerly off-limits material. I had known enough to be skeptical of some of the received mythologythat Oscar had been conceived on a restaurant tablecloth, for example, or named after a shadowy unclebut there had been other fable-filled stories, such as the accounts of Bette Daviss allegedly cantankerous presidency, that I had never squinted at quite as carefully as I should have.

The collections that had been out of view were of two primary kinds: decades worth of Academy records that had been boxed and transferred to the Academys Margaret Herrick Library in the 1990s, and the full run of Academy Board minutes.

The largely unprocessed collection of Bankers boxes, I learned as the Herricks amiably efficient staff began arraying them around me, might hold almost anything. One of the first ones I tugged thelid off of revealed the signed, marked ballots from the first Academy Awards. (Price, Waterhouse, wouldnt become the stewards, and the final repository, of the voting materials until a few years later.) Another box yielded long-lost late-1920s photographs of the Academys Club Lounge headquarters at the just-opened Roosevelt Hotelshots that even the hotels archive didnt have. One sequence of boxes was heavy with transcripts of meetings of the committees that had met when the Academy served as a mediator of industry disagreements. Small groups of distinguished filmmakers would come together to referee grievances filed by actors against producers, cinematographers against directors, and nearly every other kind of film worker who might, in the course of a shoot, decide that he or she had been unfairly used by some other party. The disputes were often amusingly gossipy, but they invariably provided sharp-focused views of the day-to-day details of early-sound-era moviemaking.