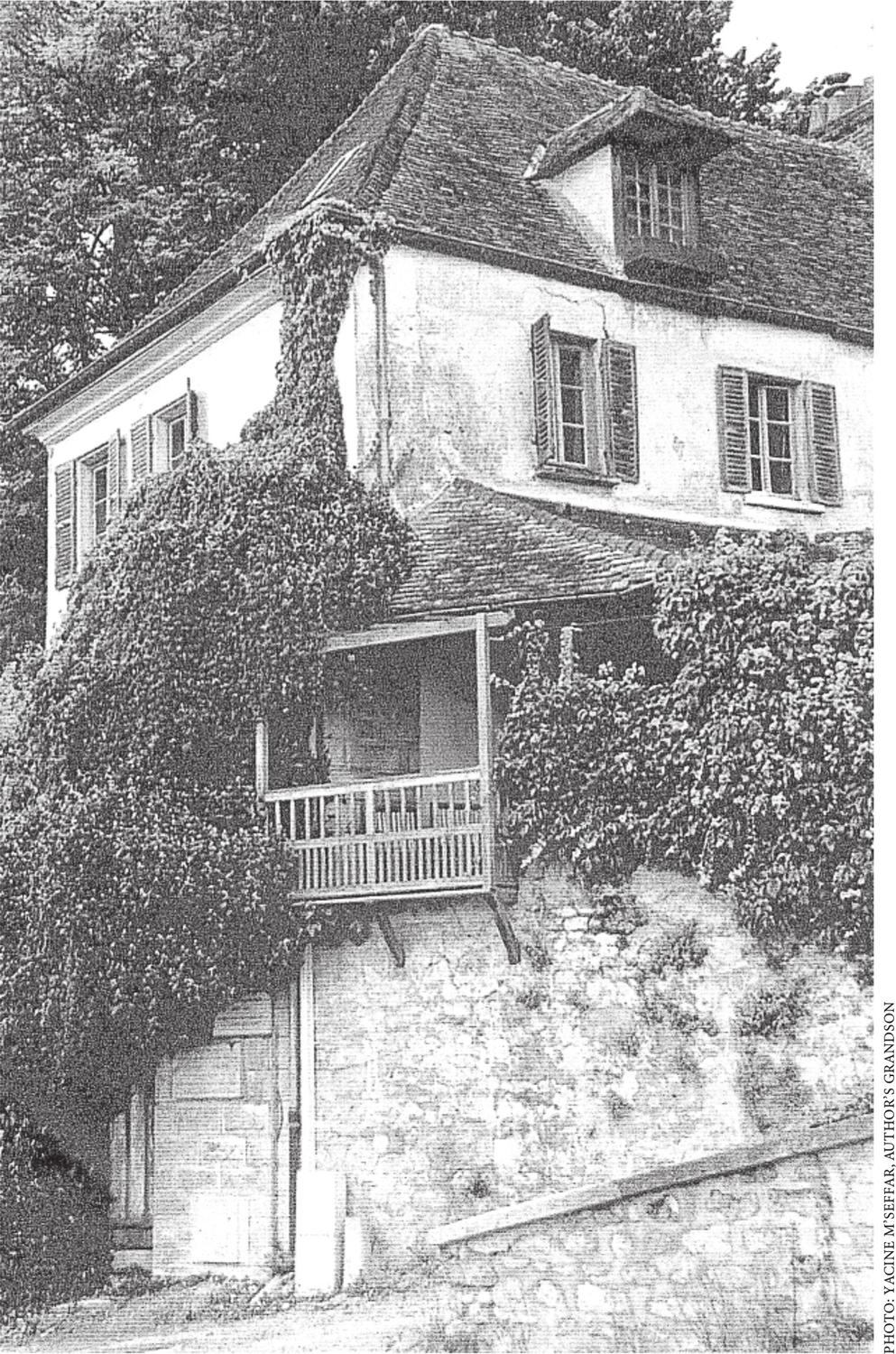

T he feel of the air that moves through the house, stirring the curtains, is the feel of June. The doors are open, and whichever way I look the garden is a continuation, a green room beyond. There is neither in nor out: not for me or for the bees that take short cuts from window to window. Even the birds sometimes make no distinction, and a nightjar blinked throughout a summer morning from the top of a bookcase beside an image of the aged St Anne. The flowers in bowls, cool as those in the garden beds, stir like the curtains. Dry lavender and curled rose-petals smell as they once did out of doors. A vine, breaking against the house with the slap of a wave, throws its tendrils upwards, and gouts of green foam lie on the windowsills. Even the light is garden light. Reflected off the tiled floor, it makes patterns like lace, like rippling water, on the ceilings. The light is above you.

Looking out through the windows, I find more rooms: terraces and plots of green, walled with box hedges. To each terrace-room an inhabitant: on this, a taciturn apricot tree that speaks, giving fruit, once in five years; on that, a smooth-stemmed catalpa, like a reserved person in a green panama. Farther off, keeping their distance, are poplars, and they also stir like the curtains, the flowers in the bowls and the light on the ceiling. They rise haphazard; this from behind a wall of stone, that from behind a wall of lavender. The house is ringed with green spires. Their trembling confuses. Sometimes you hardly know from which window you are looking.

Beyond the green spires the first landscape waits. It seems a landscape in two parts: on one side, meadows and the river with its islands; on the other the abrupt hill, the cte as the natives called it, sinewy and dry. The house itself is a tidemark; the river-meadows lap to the garden wall and no farther. We are the frontier between the water-land and the chalk-land, and there is little natural movement across the border. If a stray bird, skimming the roofs, drops from the spare hillside into the green of the river-country, it drops into another world, like a stone into a pool.

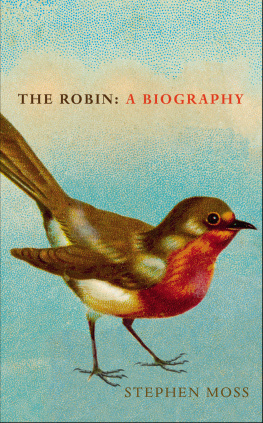

The hillside with its combes stretches for many miles, overhanging river and meadows. I knew it first as an extension of the garden, entered through a gate beyond the orchard, where wasps crawled among the fallen fruit. The slopes were rough with scrub, and in the dips and sheltered places grew copses of wild cherry, red-berried ash, and birch. Anemones and orchids flourished on the chalk soil, and through thickets I stalked birds that to my imagination were more brightly coloured than flowers. Near the crest of the hill, where you could hear larks singing over the cornland above, the slope was broken by chalk bluffs and escarpments. Mysterious caves lay at their base, whose entrances were shadowed by trees and overhung by creepers. Owls and the black redstart nested there.

The hillside was wild. Adders basked in the sun and badgers outside their setts made mounds like miniature earthworks; in a sheltered combe I once startled a hind. It was on autumn mornings that the hillside felt most remote. A river mist, risen in the night like a tide, obscured the valley below and crept to the bases of the chalk bluffs. These were transformed into gleaming sea-cliffs, whence I looked over a tumbling white ocean. The fossil shells embedded in the chalk escarpments became sea shells, as it seems they once were, and the crows and hawks, sailing on the air-currents that eddied round the bluffs, became gulls and petrels, stooping as sea birds do into the troughs of the waves but rising with mist dripping from their wings. As the sun rose, the mist receded, leaving the hillside wringing wet. Rocks and shelving beaches emerged from an ebb tide. The trees glistened as though washed, and drops pattered from the leaves.

The hillside never lost this mysteriousness of autumn mornings. It was always other than might appear to a stranger scanning it from the valley below. Even its history was not immediately apparent. Though abandoned, it had been until a century earlier planted with vines and shored with dry walls whose lapsed remnants were here and there visible. It had known a regimented life. Husbandmen had dug, pruned and sprayed, moving month after month waist-deep among maturing grapes. Along zigzag paths children had carried up the midday meal, and down the same paths peasants at evening had returned. Nothing survived of this lost activity.

Apart from myself, only a blind man was familiar with every copse and cave and with the passage of days and seasons on the hillside. Old Battouflet had taken to the cte many years earlier and lent it his protection. With his mongrel bitch and his stick, he was there in all weathers and seemed part of it, an ambulating tree. Settling in a sheltered place, where a path took a turn below the ghost of a wall or to leeward of a clump of wild cherries, he would seem by the hour to scan the tide of air that washed over the valley. From such silent scrutiny he would break without warning into scabrous songs, his hoarse voice echoing along the slopes. Hearing his chants on summer afternoons when only the crickets competed, I made wide detours to avoid him yet, when I thought myself undetected, he would hail me from the far side of a copse, as though effortlessly aware of my movements. He seemed to have uncanny knowledge of the cte and missed nothing that passed there. In time, as its only inhabitants, we became close friends in spite of the fifty years between us.

Though he was always out of doors, Battouflets skin, seen usually through a grey stubble (he was shaved by a neighbour once a week), looked unhealthily white. Its pallor owed something to the high-domed, wide-brimmed straw hat that he wore summer and winter. It kept the light from his eyes. The latter had a detached look, contrasting with the sudden violence of his language and movements. In more than their blindness they were remote from the twitching grimaces that twisted his features. The eyes both fascinated and embarrassed me. Sometimes as I surreptitiously examined them they turned on me like burnt-out moons and I had the sensation of being intensely perceived.

The time came when I sought Battouflet daily on the cte. We greeted each other as partners, the sole proprietors of a large demesne, and I commonly began by giving him the latest news of our property. I spoke with conscientious detail; he listened and asked questions. The ravens, I said, were nesting as usual on the face of the big bluff and I judged the hen bird was sitting; a new badger sett was under construction below the hanging copse where I had seen a stoat the week before. The cave that we called the Owl Cave was unsafe; water and the ensuing frost had got into the massive lobe of chalk that overhung the entrance; it might come down at any time. When Battouflet talked it was little of his days blind happenings. The hillside of which he spoke was something between the one I knew and the hillside he had once seen. He reverted to a vast oak which grew in his imagination. Rooted in a chalk escarpment, it leant into space, throwing shade on a copse far below. I searched for the tree; when I found its wreck, fallen years, perhaps decades, earlier, I dared not tell him. He also believed there were still bustard on the upland and that they sometimes strayed down the cte. He described them how they would run and then turn with an affronted stare and spread their tails. Each year he marvelled I had not seen them. You wait, he said, autumns the time; theyre less wary then.