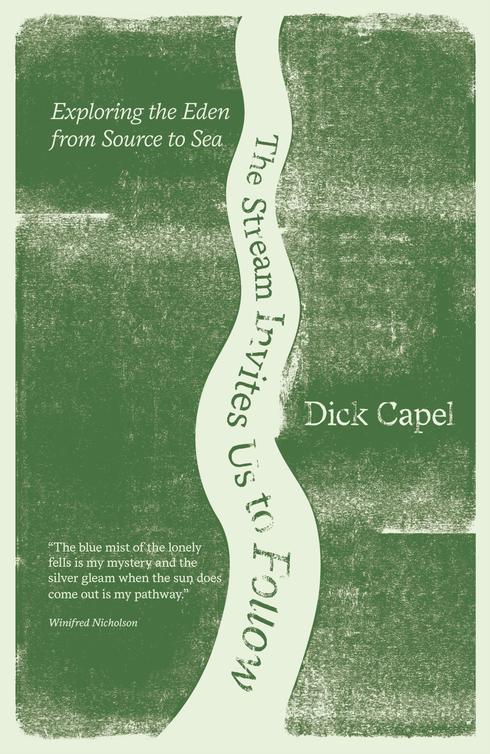

Eventually, all things merge into one and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the Worlds great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time.

Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

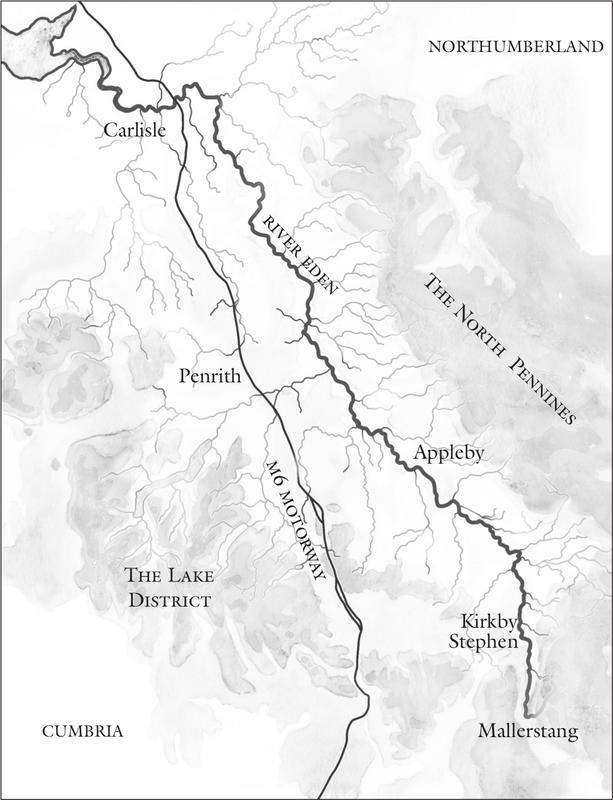

In the south-eastern corner of Cumbria, two springs of crystal-clear water called Red Gill and Slate Gutter ooze out of Black Fell Moss, a remote bog high up on the eastern side of the spectacular Mallerstang valley. Liberated from the saturated, clinging peat, they scamper over the brow of the hill and converge to form Hell Gill Beck, the boisterous adolescent stream that runs south-west down into the valley bottom and swings abruptly north to become the River Eden.

For many years, as the curlews returned to greet the arrival of spring with their plaintive, bubbling cry, I have visited the source of the River Eden; a personal annual pilgrimage after the long, cold paralysis of winter to celebrate both the awakening of the new year and the embryonic rise of the river. On one late-March visit, it didnt feel at all like spring up there; lines of thick snow lay across the moor, and grey sheets of ice glazed the pools of water skulking inside its dark peat hollows. The bleak fell was still chillingly comatose under a leaden sky, frozen in the tenacious grip of winters malevolent spell. There was no sound of the curlew that had earlier greeted my arrival in the valley below, and I listened in vain for skylarks or meadow pipits or the distant fluting of golden plovers. The morose moor was unrelentingly silent, and a screen of smoke rising on the horizon, where gamekeepers were burning the heather, partially concealed the stark outline of Ingleborough, lending emphasis to the melancholy of a lost wilderness.

I didnt stay long. My pilgrimage on that occasion was also the start of a journey along the entire length of the River Eden, which had to begin at the top of the hill known as Hugh Seat. There, at a height of 689 metres above the valley bottom, I could attain a real sense of the watershed where, as old documents describe it, Heaven water deals and Heaven water divides. With Mallerstang Edge to the east and Wild Boar Fell to the west, virtually identical heights of just over 700 metres, Mallerstang belongs, geologically, to the limestone country of the Yorkshire Dales. Dominated by horizontal layers of carboniferous limestone, capped with gritstone escarpments, it represents more than 350 million years of geological history. Derived from sediment deposited and compressed by shallow tropical seas and primeval rivers, lifted by tumultuous upheavals in the Earths crust, they were cut into shape by the interminable passage of Ice Age glaciers and the melting, manic water in their wake.

Surrounded by that vast ancient landscape, I always feel acutely aware of the fleeting and minuscule time span of human history; a mere two million years. A very small stone cairn on top of Hugh Seat, inscribed faintly with the initials AP and the date 1664, puts this neatly into perspective. The cairn is Ladys Pillar, erected at the request of an extraordinary seventeenth-century landowner called Lady Anne Clifford, the Countess of Pembroke, who owned vast tracts of old Westmorland stretching between Mallerstang and Penrith. It marks the source of the river and commemorates her notorious predecessor, the Norman knight Sir Hugh de Morville, who owned the same estates five hundred years earlier and was one of the four knights who murdered Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

My plan was to travel the route in stages, short sections at a time, sometimes walking, sometimes by car, over the course of the proceeding seasons. I descended from Hugh Seat feeling disappointed that there were no stirrings of spring at the source of the river. But I still had the warmer embrace of the green valley below to look forward to, with its promise of skydiving lapwing, their sharp pee-wit call complementing the curlews lugubrious refrain, and perhaps the sight of a few early spring flowers on sheltered grassy banks.

As I stumbled down the hill a pair of grouse hurtled out of the drab, brittle heather in front of me, whirring and gliding, a feathers breadth from the ground, on stubborn, stubby wings and seemingly mocking my retreat from the moor with their call to go bak, bak, bak, bak. At that moment one of the frozen pools erupted in a turmoil of spluttering, spouting silver bubbles, like a cauldron of boiling water. For a split second I thought Id encountered a geyser of hot spring water bursting through the peat from the subterranean depths below Black Fell Moss. Drawing closer, I realised it was frogs; a tumultuous tangle of copulating frogs rising to the surface in a frenzied orgy of vernal ecstasy. Perhaps the grouse were right and Id been too hastily dismissive of the desolate moor. In being so preoccupied with watching and listening for manifestations of spring in the air Id been ignoring the ground beneath my feet.

It was perfect. Water was going to be my regular companion as I travelled along the length of the river, and here was an entirely unexpected aquatic affirmation of renewal that lifted my spirits, filling me with an almost delirious surge of anticipation at the commencement of my journey. The now confident stream was gathering momentum, channelling its way along the bottom of the steep-sided gully it had gouged out over thousands of years. Its eroded banks are jagged with crumbling landslips and strewn with big broken slabs of stone that are testament to the waters more aggressive progress and continuing excavations after heavy rain. Scrambling down the slope into the gill, shut off from the wider landscape, I felt a profound sense of intimacy with the river. Then, as I walked along its cloistered banks, the sound of rushing water filled the air like a chorus of voices chanting a mesmeric mantra from, in Norman Macleans words, the basement of time.

I arrived in Cumbria in 1982 to work as an area warden for the Yorkshire Dales National Park in its north-west region and lived for the first twenty-five years in a sixteenth-century cottage at Fell End, on the other side of Wild Boar Fell. I lived there for eight years before I became properly acquainted with the River Eden, because my life, at that time, was being entirely shaped by the work I was doing in the upper catchment areas of both the River Ure in Wensleydale and the River Lune in Garsdale, Dentdale and the area around Sedbergh.

It wasnt until I moved jobs in 1991 and went to work for East Cumbria Countryside Project (ECCP) that I switched catchments and discovered the Eden Valley with its river and tributaries. It was a revelation in more ways than one. I had become disenchanted with my job in the National Park. At first it seemed like a dream come true; for years Id seen the national park concept as a green-print of an ecologically sustainable future for the countryside as a whole a partnership between local government and local residents, particularly the farming community, all working together to manage a productive rural economy in harmony with maintaining a beautiful landscape and a rich diversity of wildlife.

Or so I thought! Instead there was conflict and resentment at every turn. The farmers hated the National Park, and the National Park Authority maintained an aloof and condescending attitude to the farmers. Local residents, generally, grappled with inconsistent and intransigent planning restrictions. Visitor management was outmoded and still based on the American model of a national park, which, in my view, was entirely inappropriate and endlessly confusing to the public. In the UK they are not parks, nor are they nationally owned as they are in the USA. The vast majority of the farms are privately owned or tenanted by farmers who feel that they are themselves an integral part of the land they farm. They are inherently territorial, and I came to feel sympathetic to their point of view. A senior member of staff told me, in no uncertain terms, that I was becoming too friendly with the farmers, and yet I truly believed that the essence of my role was to win the trust of the farmers and recruit their support in a grand vision that would benefit everyone. As he saw it, however, I was consorting with the enemy.