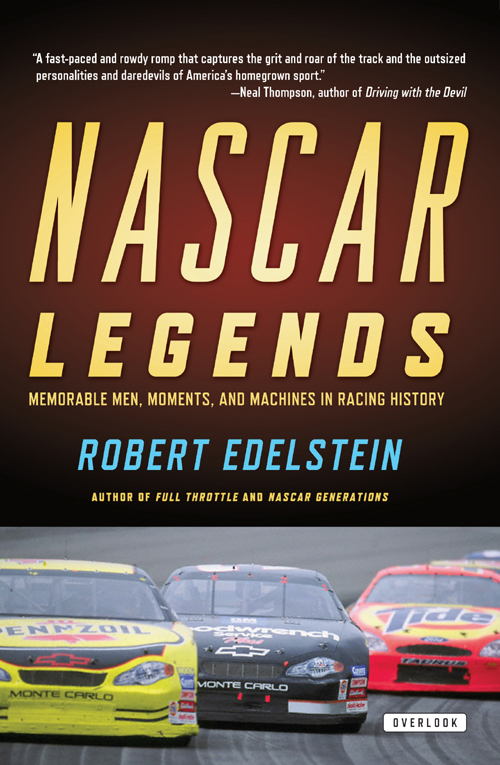

This edition first published in paperback in the United States in 2012 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact sales@overlookny.com

Copyright 2011 Robert Edelstein

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-087-1

For Loren, Dave, and my mom, and in memory of my dad

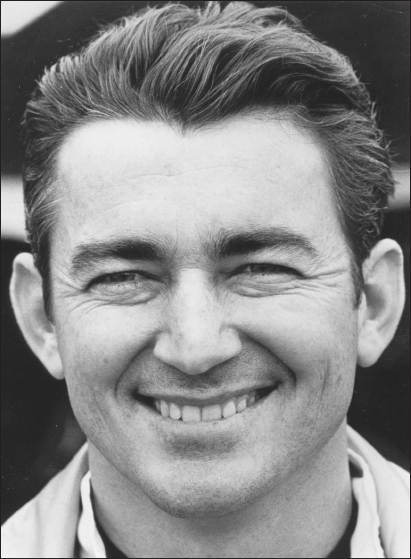

By 1969, Bobby Allison was already a popular NASCAR star on the rise.

November 1993

I have shied away from proclaiming that I am retired with the idea that maybe I will do a race somewhere, someday, rather than to be injured and put out of a career. Then I could take that checkered flag and step out of the car and say, okay, now I quit. Its a thought that makes me smile.

B OBBY A LLISON , Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, November 1993

T HEY HAD SET UP A MAKESHIFT STAGE, A WIDE PLATFORM ON RISERS , in a spacious hallway outside several ballrooms in the Waldorf-Astoria. It seemed an informal setting in such a space of old New York grandeur but it appeared to fit the occasion: a NASCAR press conference introducing the top drivers of the 1993 season. Two days later, the sports big post-season eventthe NASCAR Winston Cup championship banquetwould be held in the Waldorfs Grand Ballroom, honoring champ Dale Earnhardt. The tuxedos would be out for that one.

I was there to do my first-ever in-person interview with a stock car racer. I had done two other interviews with NASCAR drivers the previous year. The first one, with Richard Petty, had been conducted through the mail; with word that the King had hearing difficulties, his PR rep, Chuck Spicer, read me Pettys answers to questions Id sent to him. And then I did a brief phone interview with Richards son, Kyle. I found Richard Pettys answers especially intriguing. His father had knocked him out of the way in his first-ever race, and hed broken just about every bone in his body at one time or another. The quote I remember most was, I never should have driven with a broken neck.

At the Waldorf, I was going to be talking to Bobby Allison for a short 150-word item about his induction into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame. The incoming class would also include Henry Ford and Cale Yarboroughwith whom, Id later learn, Allison had fought at the end of NASCARs most famous race, the 1979 Daytona 500.

I felt completely outside my element as I stood in the hallway, watching the area fill with unfamiliar faces. It was odd to be standing around, listening in on conversations, as guys made in-jokes about other members of the press and traded anecdotes; it was all over my head.

Two guys in front of me began talking about Earnhardt, whod soon be ushered in to make some comments. The impression I got from these writers was that Earnhardt loved talking about Earnhardt, and the joys of a run of success that showed no signs of abating. Their gentle complaints were not so much about Earnhardts ego as they were about the fact that the guy had won yet again. What the hell do you write about a guy whos just won his sixth title, and his third in four years?

The Nashville Network publicist appeared suddenly; his familiar face immensely welcome. He ushered me to a corner near the back and quickly introduced me to Bobby Allison, a gray-haired man with a slightly doughy face, a shy and uncomfortable look in his eyes, and a prominent limp. He nodded and absently took my hand as I said hello. Recalling now, I might have guessed he was close to seventy. In fact, he was one day shy of his fifty-sixth birthday.

I knew his story in a sketchy way. He had lost his sons Davey and Clifford within that past year; Clifford in an on-track crash in 1992, and Davey in a helicopter accident four months before, in mid-July. Hed also had a terrible wreck five years earlier that had nearly killed him and left him physically impaired. I also knew that Bobby had won the 1983 NASCAR Winston Cup title, and a few Daytona 500s; beyond that, I hadnt researched too muchthe story was only going to be 150 words.

I was no NASCAR fan. Id vaguely heard of the new kid, Jeff Gordon. To me, motorsports was Indy Racing, with Andretti, Foyt, Gordon Johncock, and the Unsers screaming around the track in those sleek mantis-like cars.

I was thirty-three years old, a newlywed, a Jewish kid from New York; Id been talking to my wife about starting a family.

I had no idea my life was about to change, that NASCAR was soon going to become an interest, at times an obsession, and an endless fascination, and my form of fraternity with millions of strangers across the nation. Or that Id one day pride myself on knowing tiny facts about races that had been run years before I was born on gleaming dirt tracks. And that one day Id strongly consider naming my third child after Kyle Pettys oldest son.

But meeting Bobby Allison will change a person like that.

Someone came up onto that makeshift Waldorf stage and introduced Earnhardt, who climbed up the steps in boots and some kind of dark sponsors jacket, to polite applause and some smiling shouts. He grinned a lot under that mustache. He told a few jokes about the season, about winning again, and the spoils of victory, and everybody laughed their knowing laugh. I looked at Bobby once with a polite smile. He was looking down, not paying much attention.

Earnhardt called Rusty Wallace to the stage. Wallace had finished second in the points standings and it had apparently been close. They joked in that poking, friendly, competitive way; if memory serves, Rusty mentioned a race or two that spelled the difference. Again, everybody laughed knowingly.

And then Earnhardt got quiet and shushed the crowd; and he said something about how, It was a good year, but a hard year, too. We lost two good friends. So Id like to ask you all to bow your heads, and take a moment to remember Davey Allison and Alan Kulwicki.

We all bowed our heads; everyone closed their eyes and I closed mine. And I waited a good few seconds.

I know now as I knew then that it was wrong, but I felt compelled. I opened my eyes, and I turned to look at Bobby Allison.

His head was bowed slightly, his eyes were closed. And then his eyelids grew tight, and then relaxed, tight again, relaxed again. It was the look of a man trying to fend off darts of anguish. Terribly embarrassed, I quickly closed my eyes; and then I waited for Dale Earnhardt to tell me I could open them again.

* * *

I had said yes to this assignment because of Dave Glatter, my best friend when I was growing up. When we were about fourteen, we talked all the time about our crushes; I had this terrible thing for a dark-haired girl named Bobbi, and Dave liked a blonde girl named Allison. As a way to honor this secret, Dave, who was a talented artist as a kid, drew a perfect rendition of Bobby Allisons No. 12 Coca-Cola Chevy and hung it on the wall between his desk and his bed. There it remained, like some brilliant siren image, part of a lifes code that had become the great subtext language of best friends. I never forgot the clean, vibrant colors of that car. Plus, Bobby Allison shared my name, and had that cool nickname, just like one of my first heroes, Bobby Kennedy. It all seemed quite right.