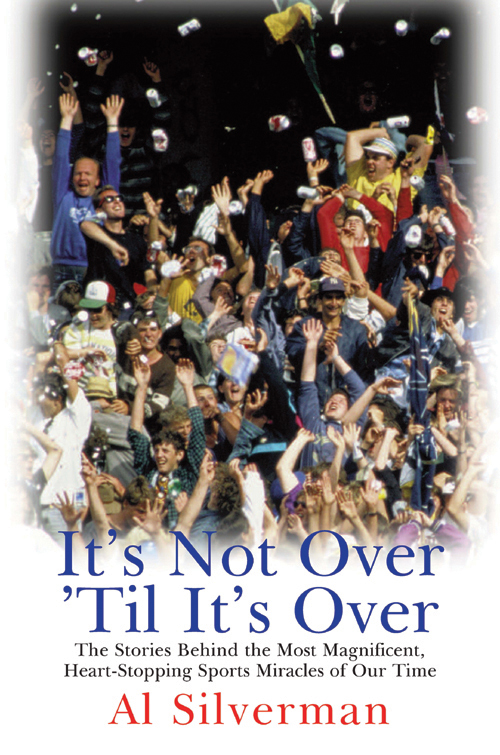

First published in the United States in 2002 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

Woodstock & New York

W OODSTOCK:

One Overlook Drive

Woodstock, NY 12498

www.overlookpress.com

[for individual orders, bulk and special sales, contact our Woodstock office]

N EW Y ORK:

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

Copyright 2002 by Al Silverman

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-431-2

For The Children of

The New Century, who

Will Help Make it Better

Ella and Zo

Jonathan, Erin, and Emma

And Louis

I always think of 1946 as one of the happiest times of my life. In June I was discharged from the Navy, where I had served 26 months as a medic. I was so pumped up by my freedom that I decided to hitchhike home from Texas, although Camp Wallace was a long way from where my family was living in Lynn, Massachusetts, just north of Boston. My first ride left me off in the border town of Texarkana, where I waited for several hours on a lonely road; I never did know whether I was thumbing a ride from Texas or Arkansas. Finally a car pulled up with two Marines who had also just been discharged. They said they were going to Boston. My new life was off to a good start.

Home in Lynn, I got another pleasant surprise. I wanted to go back to Boston University for my final three years, but I was worried that my parents wouldnt be able to find the money. Thats when I learned that the G.I. Bill of Rights would pay my tuition. I also found out that I was a member of the 52-20 cluball veterans would receive $20 a week for 52 weeks, for doing nothing. I did next to nothing that summer. I played baseball for my Jewish Community Center team, and I lolled on the beach at Swampscott, checking out which of the girls of summer had become desirable women. I also listened on the radio to the games of the Boston Red Sox as they marched regally to a pennant, only to be undone in the seventh game of the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, an early manifestation of the disease that would afflict them for the rest of the century. Then, in September, I did return to Boston University, to prepare myself for a career in journalism.

But the high point of that miracle year of 1946, for me, was the football game on Thanksgiving morning between my high school, Lynn English, and its traditional rival, Lynn Classical. The rivalry was mostly geographic. Lynn English was in East Lynn, where I lived; Classical was in West Lynn, the blue-collar section of the city. Now tons of fansEast Lynners on one side, West Lynners on the other side; no one was neutralwere filling Manning Bowl to its capacity of 20,000.

It was an ice-cold morning, with a fierce wind blowing. They had covered the field overnight with bales of hay to keep it from freezing. I dont remember ever feeling so much excitement in the air for a high school football game. Pom-pom girls from both English and Classical were strutting alongside the hay, which had been piled up on the sidelines. Drum and bugle corps from both English and Classical were on the field, blaring away in competition with each other. Everyone in the stadium seemed to be jumping up and down, maybe to keep warm, but also because of the electric charge in the air. During the season Lynn Classical had gone 10-0 and was considered one of the top high school teams in New England, largely because of its junior quarterback, Harry Agganis, who was known as the Golden Greek. My team had lost three close games that fall and was a three-touchdown underdog. That didnt mean a thing, this was English vs. Classical in the Thanksgiving Game. Anything could happen.

Sure enough. Harry Agganiss first punt, buffeted by the wind, careened out of bounds on the Classical 35. Charlie Ruddock, our tailback, who also called the plays for Lynn English, knew what he had to do. That morning, his father, Charlie Ruddock, Sr, who was a milkman (he used to drop bottles at our house in his horse-drawn wagon), a gambler and a fiery athlete in his time, told his son, Look, never mind the bullshit about giving the ball to someone else. I want you to score the first touchdown, so if you come in close, call your own playor dont come home. The father knew that the first person to score in the game would receive a bundle of giftsa pair of shoes, ten pounds of pastry from the New York Model Bakery, a new hat, dinner with his family at Lynns fanciest and only hotel, and a wristwatch. So what could his son do? He called for the ball and swept 29 yards down the sideline for the touchdown.

That was the start of a thrilling seesaw game. My team would march downfield and score. Their team would strike back almost immediately and score. With three minutes left, Lynn English led by 27-20. But with Agganiss passes clicking, Classical drove downfield scoring the final touchdown and making the extra pointa surprise pass from Agganis to his end, Vic Pujo, that tied the game and kept the team undefeated. Still, I left Manning Bowl elated. The tie was a moral victory for Lynn English.

Aside from the impact of the game itself, there are other reasons why that Thanksgiving morning 1946 remains locked into my mind. One is my obsession with Harry Agganis. It developed in the spring of 1948 when, in my first issue as editor of the Boston University News, I broke the story that Agganis, who was being courted by more than 100 colleges, would enroll at Boston University. That fall I met BU freshman Agganis, and he laughed at me for my scoop. I dont know how you knew I was coming here when I didnt know myself, he said. I followed his career closelyhis three All-America years at BU; his decision to play professional baseball instead of football, though he had been the No. 1 draft choice of the Cleveland Browns, and his quick ascent to the Boston Red Sox after less than a year in the minors. In the late spring of 1955 he was batting .313 when he went into the hospital with pneumonia. On June 26, 1955, he died of a pulmonary embolism, leaving a severe void in many peoples lives.

The other reason why that Thanksgiving day in Lynn continued to hold a special meaning for me was that the job I found in journalism, in 1951, turned out to involve sports. I went to work at Sport magazine as an apprentice editor, left in 1954 to become a freelance writer, and came back to Sport in 1960 as its editor.

Those were ideal years for a young man who had loved sports since he was a kid. Even after I left the magazine and went on to senior positions in book publishing, people kept telling me what a lucky guy I was to have been with Sport magazine. They were mainly middle-aged jocks who remembered pulling the four-color portraits of their favorite athletes out of the magazine and pinning them to their bedroom wall. I was lucky. I was able to edit the magazine and also write pieces about the leading athletes of the era. I also wrote biographies. One was of Mickey Mantle, Master Yankee. Another was of my all-time favorite athlete, the Hall of Fame pitcher, Warren Spahn. Then there was Joe DiMaggio. I still have the $500 cancelled check that I had made out to DiMaggio, who then granted me an hours interview. Though it depleted my earnings, I needed that interview to give credibility to the book I was writing on DiMaggios golden year of 1941. I also helped three stars to write their autobiographies: Paul Horning, the Green Bay Packers quarterback; Frank Robinson, the Hall of Fame slugger; and Gale Sayers, one of the greatest runners in National Football League history. The Sayers book,