Acknowledgements

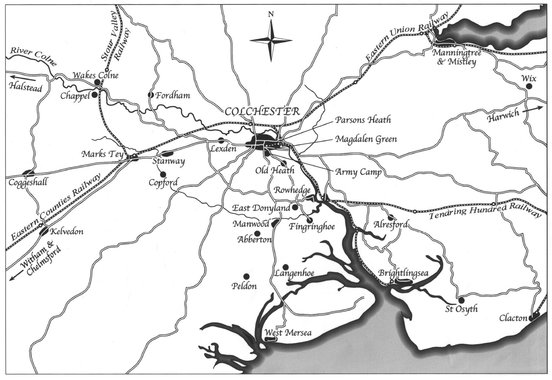

I am indebted to a number of people who have provided valuable information and assistance in support of the publication of this book. In particular, I should like to thank Jess Jephcott for information received concerning the various inns and taverns of the town, and for permission to include a number of archive photographs from his private collection. Also to Don Budds for permission to include most of the information contained in Chapter 5. To the Essex Police Museum for permission to include photographic material in their possession, and likewise to the Fordham Local History Society, the Fingringhoe Historical Recorders Group and Colchester Archaeological Trust. To Brian Light for help in producing the location map and to Christopher Doorne for his valued help in unearthing some of the foundation research material.

Finally, I should like to thank the following persons for their individual contributions: Daphne Allen, Marlene Boyle, Philip Crummy, Bryan Drane, Maureen Evans, Peter Evans, John Hedges, Horatio Hunnable, Jenny Kay, John Norman, Janet Read, Richard Shackle, Dave Tate, Reg Totterdell, Alf Wakeling, Sarah Ward and Sandra Yeomans.

If I have made any omissions, it is with regret, and in no way intentional.

CHAPTER 1

Hanged, Drawn and Quartered 1557

... another one of the bailiffs... dragged him back to the sled and

proceeded to hack off his head with a blunt cleaver...

T he process of hanging, drawing and quartering was the ultimate punishment in English law for men found guilty of High Treason women were instead burnt at the stake. This was surely one of the most brutal forms of execution ever invented and was used by Edward I (Longshanks) as a means of dispatching William Wallace of Scotland in 1305.

The full sentence required that the individual be drawn upon a hurdle (similar to a piece of wooden fencing) to the place of execution and then hanged by the neck in the normal way (ie without a drop) so as to ensure that the neck was not broken. Whilst still alive the prisoners body would then be taken down and his private parts cut off and his stomach slit open. His intestines and heart were then removed and burnt before his eyes (one, of course, would hope that by this time the poor individual was either already dead or had lapsed into a state of unconsciousness!). Next, his head would be cut off and his body divided into four quarters. Finally, the dismembered body parts would be parboiled to prevent them from rotting too quickly and then displayed in a prominent place (the head on a pole) as a warning to like-minded others.

Such was the punishment meted out to a Colchester preacher and tailor named George Eagles (nicknamed Trudgeover or Trudgeover-the-world) in 1557. George had been caught up in the anti-Protestant fervour which had been sweeping the country following the accession to the throne of the Catholic Queen Mary Tudor. This was indeed a terrible time for those of the Protestant faith as she set about trying to restore the country to Catholic Rome. First to be disposed were the Protestant bishops, including the likes of Latimer and Ridley who were both burnt at the stake, followed by the restoration of Popish rites and imagery in the churches, before finally embarking upon a fanatical crusade of religious persecution against anyone who refused to accept the teachings and doctrines of the Roman Church. During a three year period from 1555 1557 more than 300 Protestants nationwide were burnt at the stake including over seventy from Essex.

Colchester at this time was a medium-sized community with a population of about 5,000. Most of the inhabitants lived in cramped conditions within the confines of the old town wall, although the ancient borough extended well beyond these limits. The town was well known for its cloth-making industry and, almost equally so, for its religious tolerance particularly with regard to non-conformity. The townsfolk had readily accepted the principles of reform during the reign of Marys father, Henry, but now their allegiance was once again to be put to the test with her own accession, and demands for a reversal to Catholicism. The majority, of course, when faced with serious persecution, or even the threat of death, quickly recanted their new found beliefs and returned to their former Catholic ways, but some of the more steadfast supporters of the Reformation stood their ground and refused to be intimidated. From the authorities standpoint they were regarded as rebels and needed to be brought into line. By 1555 the problem locally had intensified and the town was being described as a harbourer of heretics and full of rebels.

George Eagles was one of that number, but unlike the majority of rebels to Catholicism, who were condemned as heretics, he alone was indicted for treason - simply because he had prayed that God would turn Queen Marys heart, or take her away. This had been construed as an attack on the Queen herself and wishing her personal harm. In reality, of course, he had simply been praying for her own reformation from what he considered to be an apostasy from true Christian worship.

As to what happened next, and in particular the events which led up to his capture and subsequent trial and execution, we must refer to the writings of John Foxe, one of the great Protestant propagandists of the period and the author of the well-known Book of Christian Martyrs . According to Foxe, George Eagles had begun his preaching work during the reign of Edward VI, and by the time of the Marian persecutions had become a seasoned preacher and a great encouragement to others. Little is known of his origins other than that he was a man of little formal learning and a tailor by profession. He was, however, obviously inspired with the gift of preaching and travelled widely seeking to spread his gospel message (hence his nickname Trudgeover-the-world) before finally seeking some form of refuge in and around the district of Colchester. Here he managed to keep one step ahead of the authorities, stealthily preaching by day and remaining hidden by night, often sleeping rough in the various woods and heaths which surrounded the town, breaking cover only in times of necessity.

At length, a determined effort was made by the authorities to apprehend him and bring him to justice. A reward of 20 (about 5,000 in todays money) was offered as an enticement for his capture dead or alive. And with so many spies now seeking him out he was finally spotted, purely by chance, whilst attending a fair on Magdalen Green. Although he managed to give his pursuers the slip, he was followed by a large mob who almost succeeded in catching him. However, in an attempt to throw them off the scent George had managed to conceal himself in a cornfield and had remained there quietly hidden until he was sure that his enemies had given up the chase. However, one crafty individual had decided to remain behind and, after climbing a tall tree, kept a silent watch over the area to see whether their quarry would reveal his hiding place. After some time had elapsed, and when the crowd had apparently dispersed, Eagles felt it was safe to emerge from his hiding place only to be spotted by this lone pursuer who quickly descended from the tree and apprehended him.

St Mary Magdalen church from an eighteenth century engraving. The church stood on the north side of Magdalen Green from where George Eagles was spotted whilst attending a fair. The building was demolished in 1852 and a new church erected in 1854 (since demolished). Authors collection