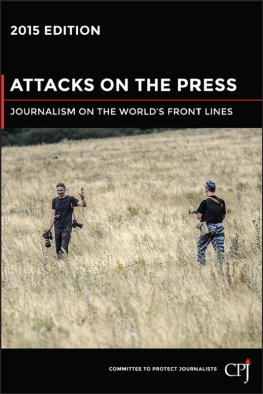

The Committee to Protect Journalists is an independent, nonprofit organization that promotes press freedom worldwide, defending the right of journalists to report the news without fear of reprisal. CPJ ensures the free flow of news and commentary by taking action wherever journalists are attacked, imprisoned, killed, kidnapped, threatened, censored or harassed.

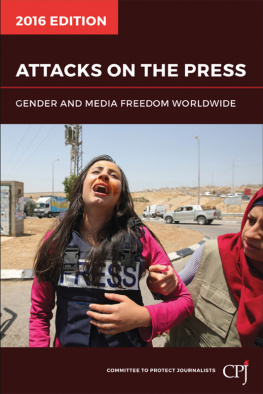

Attacks on the Press

2016 Edition

Gender and Media Freedom Worldwide

Committee to Protect Journalists

Editor: Alan Huffman

Editorial Director: Elana Beiser

Copy Editor: April Simpson

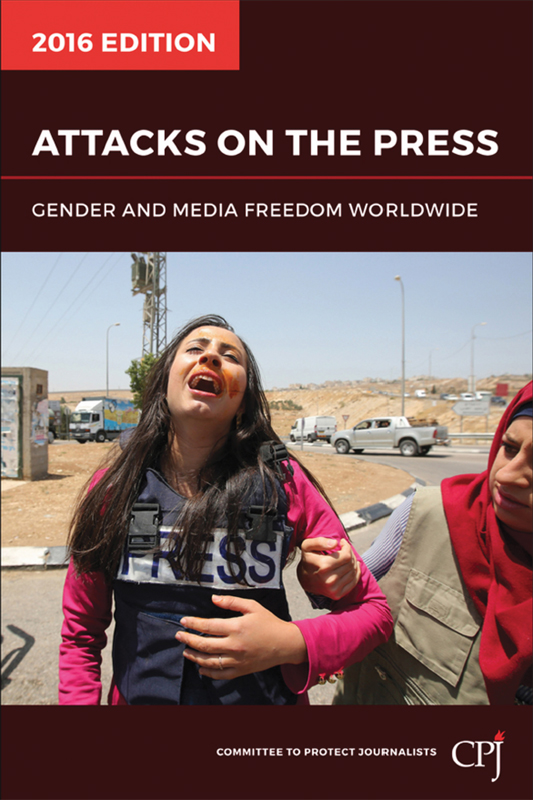

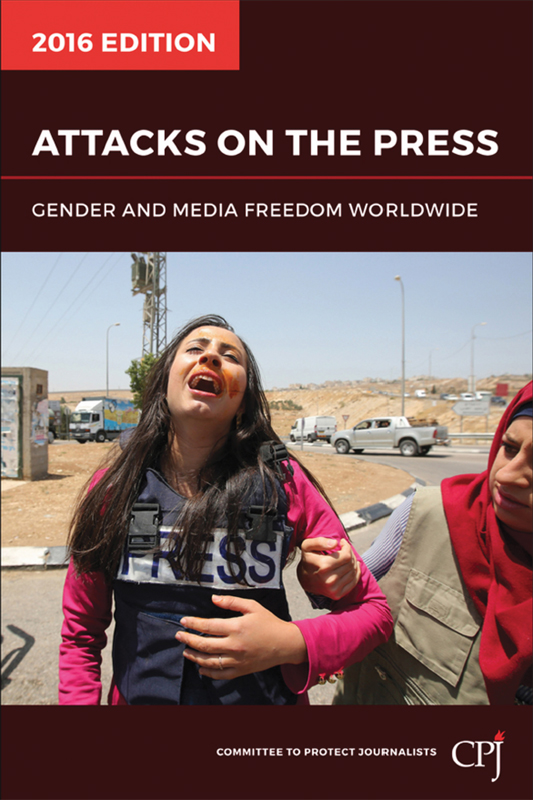

Cover photo: Jordan TV journalist Nepal Farsakh reacts after Israeli security forces spray her face with pepper gas on July 2, 2015, as she was covering a demonstration by Palestinians on a road leading to the Adam settlement, near the West Bank village of Jabba. (Abbas Momani, AFP/Courtesy of Getty Images)

Cover design: Committee to Protect Journalists

2016 Committee to Protect Journalists, New York. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

The first edition of Attacks on the Press was published by Bloomberg Press in 2013.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

ISBN 978-1-119-23090-8 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-119-23091-5 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-119-23094-6 (ePub)

Introduction Breaking the Silence

By Joel Simon

An Egyptian youth grabs a woman crossing the street with her friends in Cairo in 2012. Several female journalists were attacked in the citys Tahrir Square after the fall of Hosni Mubarak.

Source: AP/Ahmed Abdelatif, El Shorouk Newspaper

On February 11, 2011, as journalists were documenting the raucous celebration in Cairos Tahrir Square following the fall of Hosni Mubarak, the story took a sudden and unexpected turn. CBS 60 Minutes correspondent Lara Logan, who was reporting from the square, was violently separated from her crew and security detail by a mob of men. They tore her clothes from her body, beat her and brutalized her while repeatedly raping her with their hands. Logan was saved by a group of Egyptian women who berated her attackers until a group of Egyptian army officers arrived and took her to safety.

Details of the attack on Logan were sketchy, and in the immediate aftermath there was a good deal of confusion and some predictable but unfortunate criticism as well. Some raised questions about Logans judgment in reporting from Tahrir Square at a volatile moment. Others questioned the appropriateness of her dress.

But there was a more serious concern among leading female journalists with whom I was in touch at the time. They worried that the intensive coverage of Logans attack could affect them professionally. These journalists had throughout their careers overcome discrimination and resistance from editors and managers in taking on the most dangerous and difficult assignments. They worried that a focus on the risk of sexualized violence would reinforce resistance from editors. The concern was not entirely academic. In November 2011, after a sexualized attack on a French journalist, Caroline Sinz, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) issued a statement noting, This is at least the third time a woman reporter has been sexually assaulted since the start of the Egyptian revolution. Media should take this into account and for the time being stop sending female journalists to cover the situation in Egypt.

The response was immediate and fierce. Writing in the Guardian,

At CPJ, we faced criticism of our own. Many friends of the organization pointed out that we had not done enough to document sexualized violence and that we did not collect the kind of comprehensive data we have on killed and imprisoned journalists. Of course, it is more difficult to document sexualized violence because of its stigmatizing nature, but our then-senior editor, Lauren Wolfe, demonstrated that it could be done through persistence and determination.

During the three months following the attack on Logan, Wolfe interviewed dozens of reporters, who described their experience with sexualized violence, many speaking publicly for the first time. These incidents ranged from rape to groping and harassment during demonstrations. Victims told Wolfe that they had not spoken out for a variety of reasons, including societal norms, a belief that authorities would not pursue an investigation, and, most distressingly, a concern that they would face discrimination in their own newsrooms.

The CPJ report was dubbed The Silencing Crime,

On May 1, 2011, Logan was interviewed on 60 Minutes by her colleague Scott Pelley and described her experience in unflinching detail. When asked why she was speaking out, Logan said she wanted to break the silence, noting that women never complain about incidents of sexual violence because you dont want someone to say, Well, women shouldnt be out there. But I think there are a lot of women who experience these kinds of things as journalists and they dont want it to stop their job because they do it for the same reasons as methey are committed to what they do. They are not adrenaline junkies, you know, theyre not glory hounds, they do it because they believe in being journalists.

Next page