Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to the following:

I. Armas, David Bellis, Rochelle Bloch, Estela Bravo, Cadena de Turismo Islazul, Enrico Cirules, Cubana Airlines, Vivian R. Carillio, Cristina, Aristides V. Chap, F. Ramirez Garca, Claire McDonald, Martin di Giovanni, Robert van der Hilst, Michael and Pebbles (especially for the title), Laurel Grant, Angel Luis F. Guerra, Jane King, Ana Rosa Lara, the late Claudia Lightfoot, the Maleta family, Mara Elena, E. Marquez, M. Morales, R. Monzote, Joseph Mutti, Giolvis D. Osoria, Jim Pett, R. Ramirez, F. Reyes, Raquel Rubi, David Stanley, Y. Triana, Nersa. C. Veloso, S. Wilkinson.

And to the many people who asked, for differing reasons, that their names not be included above, your help is not forgotten.

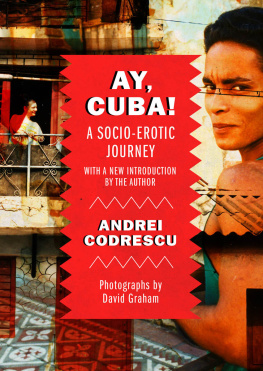

Preface

Though it is rarely possible these days to arrive at a new somewhere with no preconceptions at all, as a travel writer I avoid over-researching a destination. Before arriving in Cuba, I knew as much as most well-informed people about the country, about U.S. attitudes towards it and the problems the island had faced since the collapse of the Soviet Union over a decade earlier. The networking Id done in the UK prior to leaving for Cuba brought me into contact with men and women who were staunchly pro-Castro. Those meetings, coupled with my own liberal, left-leaning views, gave me an optimistic outlook about what I would find there. When I travelled through Cuba in the winter of 20001, the Revolution had been happening for more than 40 years and was, according to the government, still underway.

Rereading now what I wrote then, Im struck by how much the feelings of the people I met and spent time with affected my experience of the place and the way I wrote about it on my return home. Cubans are passionate people, and not only for music, dancing and rum, as international tourism promotion suggests. Cubans are passionate about many things: the rights and wrongs of a situation, the weather, freedom and food, to mention just a few. As I travelled from rainy Havana to rainy Baracoa, I began to realise that freedom and food were important to ordinary Cubans chiefly because they didnt have much of either. This didnt mean that the rum, the salsa and the wonderful musical extravagance of Cuba werent real, but, as I travelled and met people who showed me the interiors of their homes and lives, the Cuba of my imagination quickly vanished. Alongside sun, salsa and organic farming, I found a dark, melancholy sensibility, a Caribbean Gothic that was more complex, exotic and exciting than anything I had been led to suppose by British communists tales of youth movements and the Triumph of the Revolution. It is this unique Gothic quality, rather than mojitos and dirty dancing, that readers will find reflected in the pages that follow.

Nothing will ever change here. These were the exact words said to me by teachers, hairdressers, artists and taxi drivers from one end of Cuba to the other. Many of the people I met were too young to have known anything except Fidel Castro and his 1959 revolution. Having had only limited access to information about the vast and sweeping changes that took place in Central and Eastern Europe in the early 1990s, few Cubans could conceive that such change might also be possible in their own country. Today Cuba is at the very beginning of the end of its revolution. Fidel is no longer president, though he still leads the Communist Party and casts his tall shadow over the new president, his brother Ral. So, although very little has changed as yet on this island, whose largely unspoilt shores lie only 145 kilometres from the extremes of Floridas hedonism, everyone knows that half a century of revolution is almost over and that, one day in the not-too-distant future, things will change and life will never be the same again. For most Cubans this is a thrilling and appalling prospect.

Despite the gloom most people expressed to me about their lives, I left the country with a powerful sense of the complexity of what it means to be Cuban in the 21st century. Cuban writers, musicians and athletes are world class; the country sends its doctors to treat the poorest of the poor around the world, while the West cheerfully drains those same countries of their medical professionals. While passionate about inadequate salaries, the lack of basic foodstuffs, restrictions on travel, communication, information and education, which they felt should be up to date and truly free, the Cubans I met were intensely proud of their country, of the fact that they are not a U.S. satellite, despite everything that that country has thrown at them. They were proud of their revolution which has cost them so very much.

Will the country as the world has known it for half a century change forever when the Castro brothers join Jos Mart and Che Guevara in the great revolution in the sky? Whenever and however change finally happens, I hope, perhaps somewhat navely, that the Cuban people, who have endured so much for so long, will at last be allowed to decide their own future, free of pressure from within, or without, the shores of their beautiful island.

Zo Brn, London 2008

Arrival

Elsewhere is a negative mirror. The traveler recognizes the little that is his, discovering the much he has not had and will never have.

Italo Calvino,

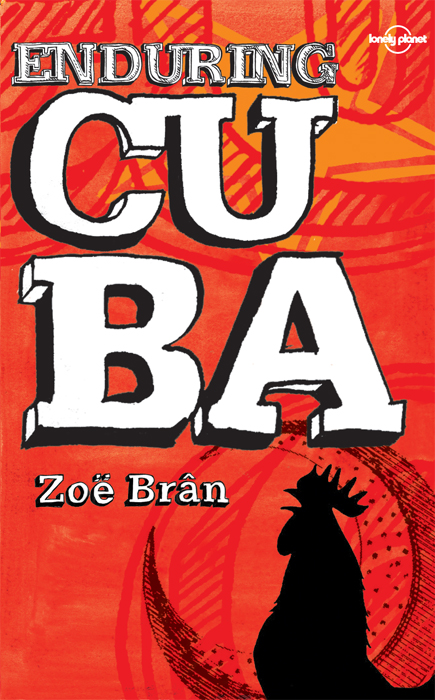

Enduring Cuba

Enduring Cuba