All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Introduction

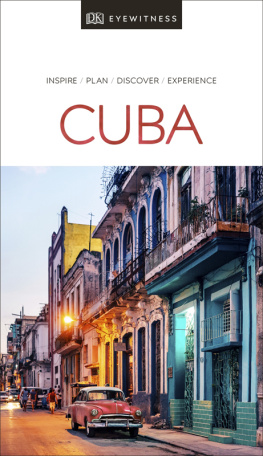

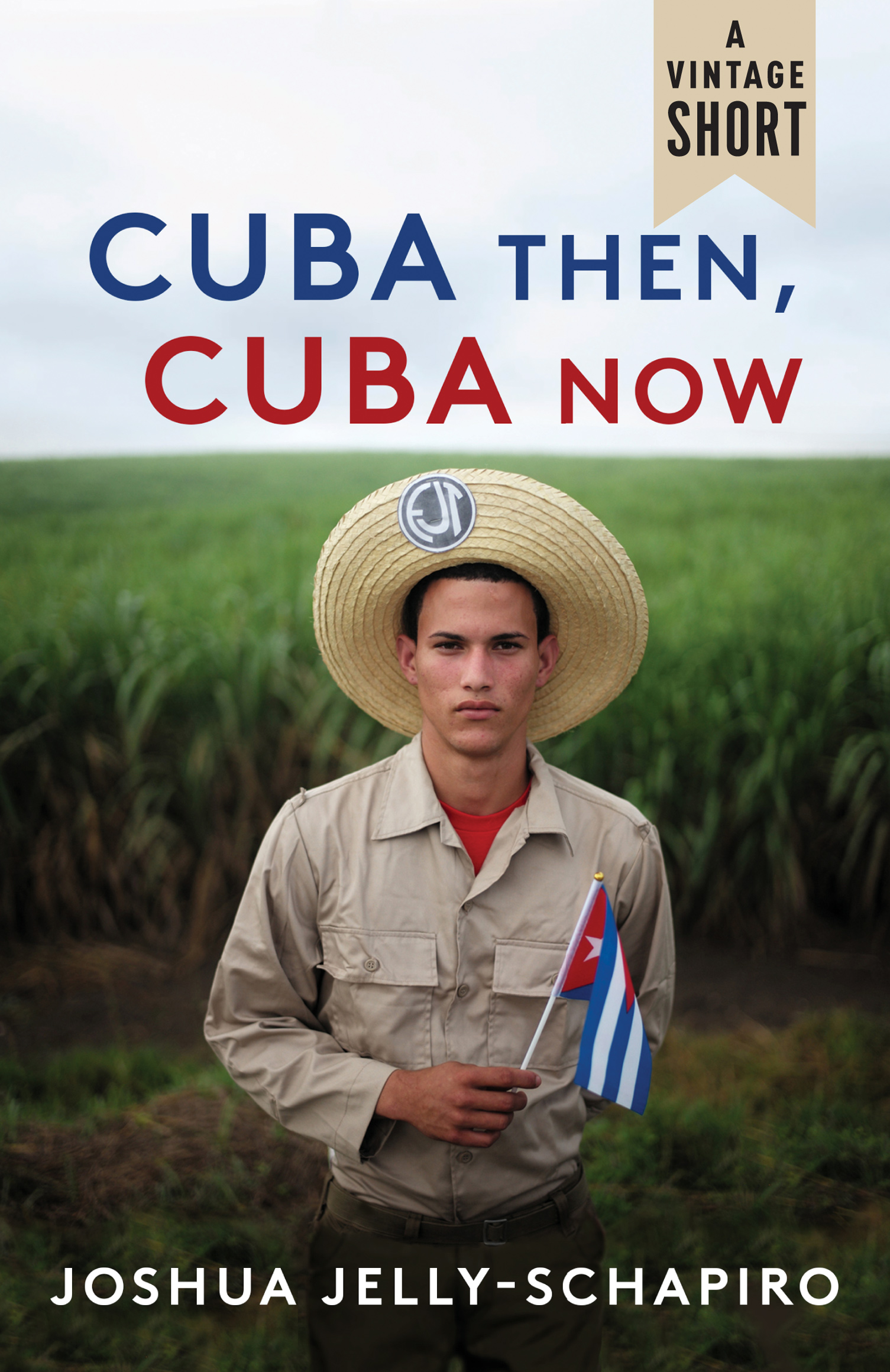

For a man long said to be the only Cuban who didnt dance, Fidel Castro always had a stellar sense of timing. Before he died in 2016 at age ninety, Cubas leader for half a century was also a bogeyman for six U.S. presidents, a hateful villain to Cubans in Miami whose island he stole in 1959, and an outsized hero across what was once called the third world. As a politician who was also his countrys foremost celebrity, the bearded icon known to his countrymen as Fidel grabbed every spotlight he couldwhether by turning up, in his revolutions early years, just in time to be photographed helping his troops repel invaders at the Bay of Pigs or by appearing on a ferryboat in Havanas harbor, decades later and after that revolution had soured, to remonstrate with fleeing countrymen trying to hijack the vessel to Florida. But as the survivor of hundreds of attempts on his life, he had a keen sensehis fondness for hours-long speeches notwithstandingfor when to seize or exit a stage. Which is perhaps why the timing of his death, which he managed to effect on his own terms and as an old man in bed, shouldnt have been surprising. His younger brother, Rul Castro, Fidels successor in power, announced the physical disappearance of Cubas eternal comandante on November 25, 2016mere days after the nearby nation that served as Fidels bte noire elected Donald Trump president.

This coincidence didnt go unnoticed on the Internet. One meme that went viral after Fidels death recalled that he had promised, long ago, that hed only let himself expire when elimperiothe United Statesfell apart. If the ascent there of a vain buffoon who won the White House by tweeting lies from his phone signified to Fidel that this day had come, he wasnt alone. Either way, that momentous month in the northern hemisphere saw the demise of one figure who symbolized an era and the rise of another who may do the same. The nearness of events felt dramatic indeed, in two countries long joined by what a leading scholar of U.S.Cuba relations termed ties of singular intimacy. And especially so, given some dramatic recent changes in their bilateral ties.

Those changes would have been quite unimaginable during the Cold War, to Fidel and everyone else. They saw Rul Castro respond to historic entreaties from Barack Obama in ways Fidel never could haveand take significant steps, after his and Obamas joint announcement of dtente in late 2014, toward burying the mighty hatchet that had for sixty years defined U.S.Cuba relations.

Among the resultant shifts was a lifting of limits on Americans ability to visit Cuba. By late 2016, these changes had already allowed a million peoplecurious tourists enticed here by Buena Vista Social Club and also Cuban Americans thrilled to be able to visit kin as they wishedto board new direct flights to do so. They also allowed me, days after Fidels death and as a devotee of Cuba who for twenty years had grown used to traveling here as a journalist and researcher only via Canada or Mexico, to have a novel experience: I called up JetBlue and booked a simple forty-minute flight from Fort Lauderdale to the provincial town of Holgun, in Cubas rural east, to catch the end of a funeral cortege that saw Fidels cremated remains driven the islands length in a little green jeep. The solemn procession ended in the city where Fidel first made his name, Santiago, and where hes now interred in a grave marked by a twenty-ton granite boulder hauled there from the nearby Sierra Maestra and affixed with a bronze plaque inscribed with a single word: FIDEL.

That funeral, and a fateful election in the United States, is what November 2016 will be recalled for by historians. My closer relations and I will also recall that month for the publication of my book, Island People. That book, many years in the making, comprised a portrait of the Caribbean that approached the regions islandsfrom Cuba to Puerto Rico, Jamaica to Trinidad, Barbados to Martiniquenot in the way theyre often imagined these days: as exotic spots to vacation. Island People, rather, understood the nations of the Greater and Lesser Antilles as places that belong at the center of any story we tell ourselves about the making of our modern world.

These fertile islands, long before their shores became famed for sun and sand, were the rocks into which Columbus bumped on his hunt for Asia and where globalization began. Theyre where the Triangle Trade was then centered, for three centuries, by colonial powers who brought six million enslaved Africans to the Caribbean to grow sugar for European tables. In that trades most lucrative and brutal plantation colony, the French sugar island of Saint Domingue, a half million slaves rose up to kill their masters and ask the West, in 1791, if human rights applied to black people, too. The triumph of Haitis Black Jacobins birthed modern politics. The Haitian Revolution, contended its great chronicler C. L. R. James, also shaped the emergence of a new Caribbean civilization. That civilization spanned the French and English and Spanish islands alike, and its membersC. L. R. James included: he was born in the English crown colony of Trinidad in 1901were destined to have a unique role in world history over the span of time implied by the title of Jamess seminal essay, From Toussaint LOuverture to Fidel Castro. His arguments, in that piece, shaped my approach for a region whose plurality of islandsincluding Trinidadwon self-rule in the years after World War II.

The Caribbeans uniquely modern societies were built by people who moved vast distances, centuries ago, to toil at industry; who lived in societies shaped by global trade and cultural mixing from the start; who were forced, long before the subject nations of Africa and Asia became part of Europes empires, to learn Europes languages and make them new. Among the hundred-odd erstwhile colonies, worldwide, reborn as nations in the postwar era, the peoples of the Caribbean were the most highly experienced in the ways of Western civilization, wrote C. L. R. James in 1963, and most receptive to its requirements in the twentieth century. They were the best placed among all the worlds once-colonized people, in other words, to shape culture everywhere in our era.