ALSO BY

JOSHUA JELLY-SCHAPIRO

Island People: The Caribbean and the World

Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas

(with Rebecca Solnit)

Copyright 2021 by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Jelly-Schapiro, Joshua, author.

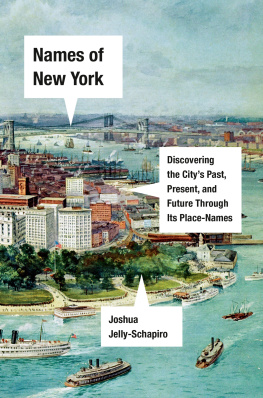

Title: Names of New York : discovering the citys past, present, and future through its place-names / Joshua Jelly-Schapiro.

Description: New York : Pantheon Books, 2021. Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020037287 (print). LCCN 2020037288 (ebook). ISBN 9781524748920 (hardcover). ISBN 9781524748937 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Names, GeographicalNew York (State)New York. New York (N.Y.)Historical geography. New York (N.Y.)History.

Classification: LCC F128.3 .J45 2021 (print) | LCC F128.3 (ebook) | DDC 974.7/1dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020037287

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020037288

Ebook ISBN9781524748937

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover image: A Birds Eye View of Lower Manhattan, 1911, by Richard Rummell. The New-York Historical Society, U.S.A./ Bridgeman Images

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

a_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

For Mirissa

CONTENTS

1.

THE POWER OF NAMES

Names matter. Just ask any parent agonizing over what to call a newborn. Or any kid burdened with a name they hate. Just think of the song made popular by Johnny Cash, about a boy who explains that life aint easy for a boy named Sue, and confronts the father who named him (My name is Sue. How do you do! Now you gonna die!). Whether you traverse your life as a Jane or an Ali or a Joaquin or an Eveor you decide, as a grown-up, that youd rather endure or enjoy it as someone elsewe all learn that names mark us. Totems of identity, systems of allusion, names can signal where were from, who our people are, who we attach ourselves to, which Bible character or dead relative or living movie star our namers loved best. Murmured by an intimate or yelled by a foe, a name can be an endearment or a curse. Declaimed by protesters in the street, a name becomes an assertion of dignity, of rights, and of the refusal to overlook or forget. Names are shorthand, theyre synecdoche. They are acknowledgments or shapers of history, containers for memory or for hope. And if names matter so much when attached to people, they matter even more when attached to places, as labels that last longer, in our minds and on our maps, than any single human life.

Name, though it seem but a superficial and outward matter, yet it carrieth much impression and enchantment. Thats how Francis Bacon described the matrix of associations we affix, consciously or not, to the public words by which we navigate our days. Place-names can bind people together, or keep them apart. They can encode history and signal mores. They can proclaim what a culture venerates at one moment in time, and serve as vessels for how it evolves and shifts later on. Gettysburg, Attica, Stonewall, Rome. Wall Street, Main Street, Alabama, Prague. Malibu, Beirut, Boca Ratonplace-names can summon worlds and evoke epochs in just a few syllables. They can recall long-ago events or become, as settings for more recent ones, metonyms for historical change. Place-names can become styles of dress (Bermuda shorts, Capri pants) and of dance (once we did the Charleston, now we do the Rockaway). They can hail rebellions or honor heroes or spring, like Sleepy Hollow and Zion, from books. Whether a names born of whimsy or faith, whether it was first written down by a cavalier in his log or a bureaucrat in a city hall, its impression and enchantment derives, too, from the truth that its meaning cant be fully divorced from its roots.

In place-names lie stories. Stories, in the first instance, about their coinerstales, say, about the long-ago Dutchmen who wandered an island of wetlands and hills that the people who lived there may or may not have called Mannahatta, but whose northern acreage those Dutchmen named for a marshy town in Holland called Haarlem. Then there are also stories about the complex or contradictory processes by which certain labels come to be recognized as official. Stories about how people, singly or in groups, attach certain attributes to place-names that grow iconic (iconic of, for example, as with twentieth-century Harlem, Black culture and pride). And stories, too, about all the ways that such words thus do much more than merely label location. About how these wordsin their rhythm and sound and how they look rendered into Roman letters or affixed on street signs and mapsshape our sense of place.

Toponymythe study of place-namesisnt a well-known field. Say the term toponymist even to a professional geographer, and youll conjure a hobbyist or word hoardera figure seen as a compiler of useful trivia. Some of us find our minds fed and our road trips improved by this kind of trivia, by learning, for example, that American place-makers fell in love with two sophisticated-sounding suffixes meaning town, one borrowed from German (-burg) and one from French (-ville), with which they ran wild in naming Hattiesburg and Pittsburgh and Vicksburg and Fredericksburg and Charlottesville and Hicksville and Danville (a village in Vermont near where I grew up, which one might incorrectly guess is named after a guy named Dan). We are intrigued to learn that during another bout of Francophilia, in the late 1800s, city planners who had wearied of the mundane word street began calling the broader ones by a termavenuewhich in France meant a tree-lined drive to a grand estate. Who, while walking down Manhattans Mulberry Street, does not find the trip made richer by pondering how its blocks, long before they became home to Italian immigrants and then to the restaurants that still make its name synonymous with the best cannoli, were home until the 1850s to an actual mulberry tree? As legend, if not history, has it, the Gangs of New Yorkera folk hero Mose Humphrey pulled the tree up by its roots and used it to bludgeon rival toughs from the Plug Uglies.

Toponymy, at its simplest, is all about such bits of knowledge and lore. But as George R. Stewart, the doyen of American place-name lovers, observed, the meaning of a name is bigger than the words composing it. And Marcel Proust agreed: In Swanns Way, he described how place-names magnetized my desires in his youth, not as an inaccessible ideal but as a real and enveloping substance. The names that obsessed him werent matched by the actual places; Parma was compact, smooth, redolent of Stendhalian sweetness and the reflected hue of violets, unlike the fusty and sprawling burgh in Northern Italy that he later visited. Proust was making a point similar to one that geographer Yi-Fu Tuan made in his book