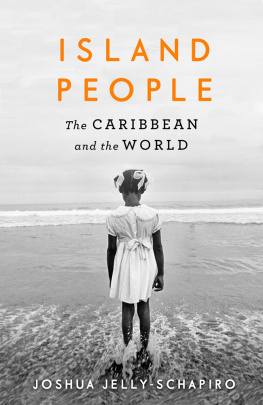

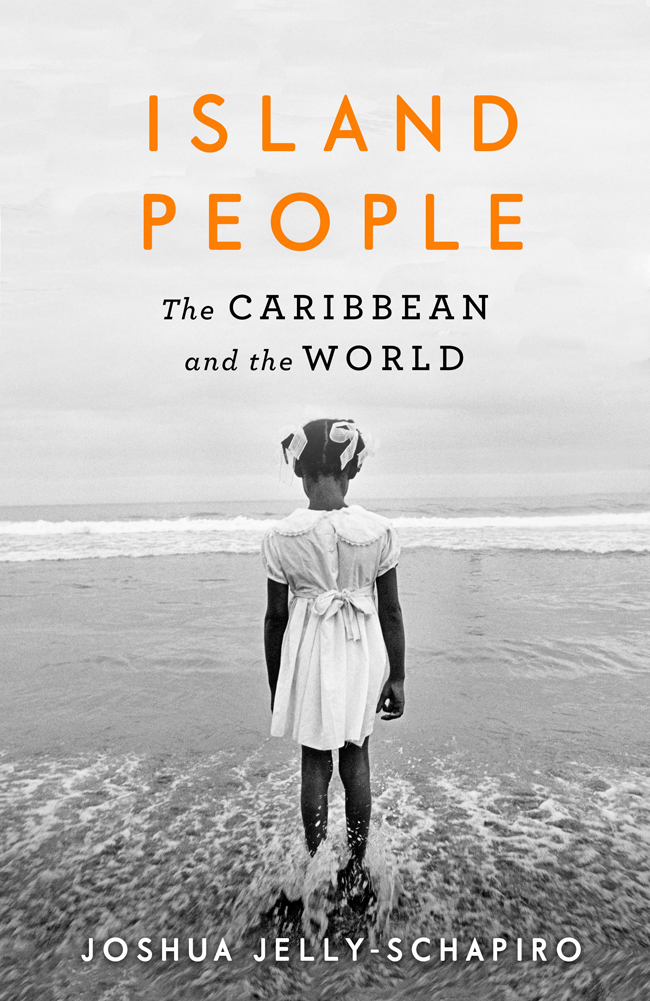

Joshua Jelly-Schapiro - Island People: The Caribbean and the World

Here you can read online Joshua Jelly-Schapiro - Island People: The Caribbean and the World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Knopf, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Island People: The Caribbean and the World

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Island People: The Caribbean and the World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Island People: The Caribbean and the World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Island People: The Caribbean and the World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Island People: The Caribbean and the World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Published in Great Britain in 2017 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

www.canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2017 by Canongate Books

Copyright Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, 2016

First published in the United States of America by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78211 558 8

EXPORT ISBN 978 1 78211 559 5

eISBN 978 1 78211 560 1

For my parents

and for island people everywhere

The indigenous Carib and Arawak Indians, living by their own lights long before the European adventure, gradually disappear in a blind, wild forest of blood. That mischievous gift, the sugar cane, is introduced, and a fantastic human migration moves to the New World of the Caribbean; deported crooks and criminals, defeated soldiers and Royalist gentlemen fleeing from Europe, slaves from the West Coast of Africa, East Indians, Chinese, Corsicans, and Portuguese. The list is always incomplete, but they all move and meet on an unfamiliar soil... in an unpredictable and infinite range of custom and endeavour, people in the most haphazard combinations, surrounded by memories of splendour and misery, the sad and dying kingdom of Sugar, a future full of promises. And always the sea!

George Lamming

Were all in the Caribbean, if you think about it.

Junot Daz

CONTENTS

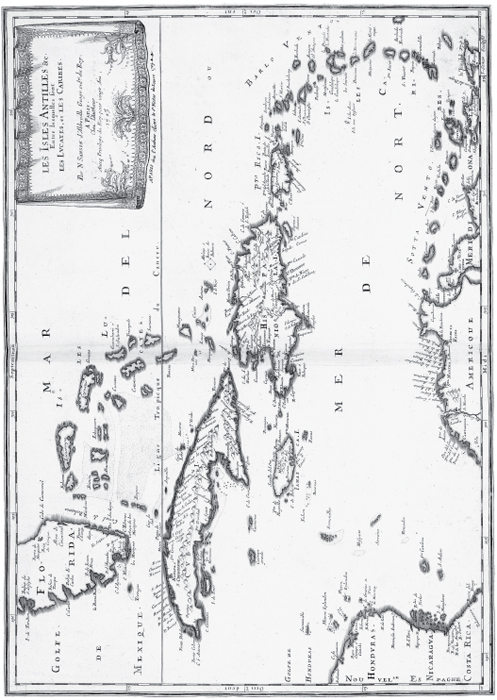

David Sanson and Guillaume Sanson, Les Isles Antilles (1703). COURTESY OF THE DAVID RUMSEY HISTORICAL MAP COLLECTION

INTRODUCTION

IN NOVEMBER 1963, Vintage paperbacks published a new edition of The Black Jacobins, C. L. R. Jamess celebrated history of the Haitian Revolution. The book had first appeared in London in 1938, where James had arrived by transatlantic steamer from his native West Indies a few years before to launch a literary career. A quarter century later, The Black Jacobinsthough already a touchstone for black intellectuals worldwidehad fallen out of favor and out of print. Its itinerant author had moved from England to the United States shortly before World War II, then had returned to Europe after being expelled from the U.S. as a subversive in 1953. Finally, in 1958, he returned to his home island in the southern Caribbean for the first time since hed left his life there as a colonial schoolteacher.

Born in British-owned Trinidad in 1901, C. L. R. James was the son of a schoolmaster and a cultured mother whose bookcase of Victorian novels and Elizabethan drama occupied him when cricket didnt. He grew into a radical whose passion for dramatic narrative always equaled his yen for discourse on historical materialism. ([Thackerays] Vanity Fair holds more for me than Capital, he said.) Drawn to the classics and hugely ambitious, James sought to place the history of the Caribbean within the larger telos of not only modernity and capitalism but also humanitys struggle for democracy, reaching back to the Greeks. Perhaps more distinctively, he sought always to understand the cultures of his own daycricket matches and calypso songs, Hollywood films and radio serialswithin that larger story.

James Baldwin wrote, I believe what one has to do as a black American is to take white history, or history as written by whites, and claim it allincluding Shakespeare.

Jamess return to the Caribbean was prompted by the promise of self-rule in Trinidad and the triumph of the Cuban revolution. And it was these same momentous developments that prompted his decision to publish a revised edition of his history of the epochal slave revolt, led by Toussaint LOuverture, through which West Indiansand not only Haitiansfirst became aware of themselves as a people.

James left the main text of The Black Jacobins unchanged, except for the addition of several lambent lines about Toussaints sad demise. More substantively, James included a postscript appendix in which he offered a new interpretation of the Haitian Revolutions significance. This new afterwords thrust was conveyed in its title: From Toussaint LOuverture to Fidel Castro. Rather than signifying a merely convenient or journalistic demarcation of historical time, Toussaint and Fidel were joined because each man had led revolutions that were peculiarly West Indian, the product of a peculiar origin and a peculiar history, no matter that they occurred 150 years apart and on different islands. The Caribbean was a region whose peculiar history, according to James, had not only produced a common culture on its islands but given them a special role to play on the world stage.

He sought, in his new afterword to The Black Jacobins, to explain why. The history of the West Indies is governed by two factors, the sugar plantation and Negro slavery, he began.

Wherever the sugar plantation and slavery existed, they imposed a pattern. It is an original pattern, not European, not African, not a part of the American main, not native in any conceivable sense of that word, but West Indian, sui generis, with no parallel anywhere else.

The plantation and racial slavery had been present elsewhere in the Americas. But the Caribbean, James argued, was unique. Firstly because of sheer numbers: from the early 1500s through to the end of the Triangle Trade, three centuries later, the regions islands received some six million African slaves to their shores (Englands North American colonies that became the United States, during that time, received scarcely 400,000). And secondly, the region stood out for the particular nature of the lives its slaves lived. Those slaves, as builders of island societies made for the express purpose of providing sugar for distant tables, had from the sixteenth century on lived a life that was in its essence a modern life.

For James, these facts were far from mere historical trivia; they were crucial to understanding the role that the Caribbeans people were fated to play in world historyand in the world-historical development that would define the postwar era: the dismantling of Europes colonial empires across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and the emergence of its old colonies people as full-fledged members of the world comity of nations. It was not by accident, James argued, that West Indians had formed the vanguard of black thinkers driven to end colonialism worldwideas evidenced, for example, by figures like Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, and by Frantz Fanon, the Martinique-born author of The Wretched of the Earth (to say nothing of James himself). And it was not by accident, either, that the islands wherein the worlds first truly modern revolution took place (in Haiti) had also just witnessed a triumph for socialism and guerrilla tactics, in Cuba, that freedoms lovers everywhere were touting at the time as the model for how the earths wretched should right historys wrongs.

Jamess arguments were driven by politics: an ardent leftist, he was also writing at a time when he, like many West Indian intellectuals, was still hoping the Caribbeans islands might confederate into a single regional nation. But what was at stake for him in arguing that the Caribbeans diverse territories shared a common history and culture was not merely that such an understanding was necessary for the Caribbeans self-realization. It was what that self-realization might entail The Caribbean and its diasporas were destined, in other words, to play a special role in the development of world culture at large in the twentieth century.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Island People: The Caribbean and the World»

Look at similar books to Island People: The Caribbean and the World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Island People: The Caribbean and the World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.