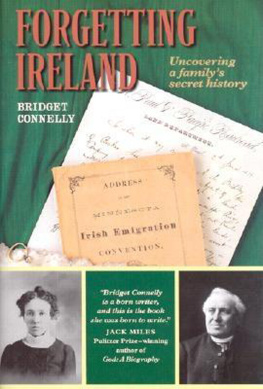

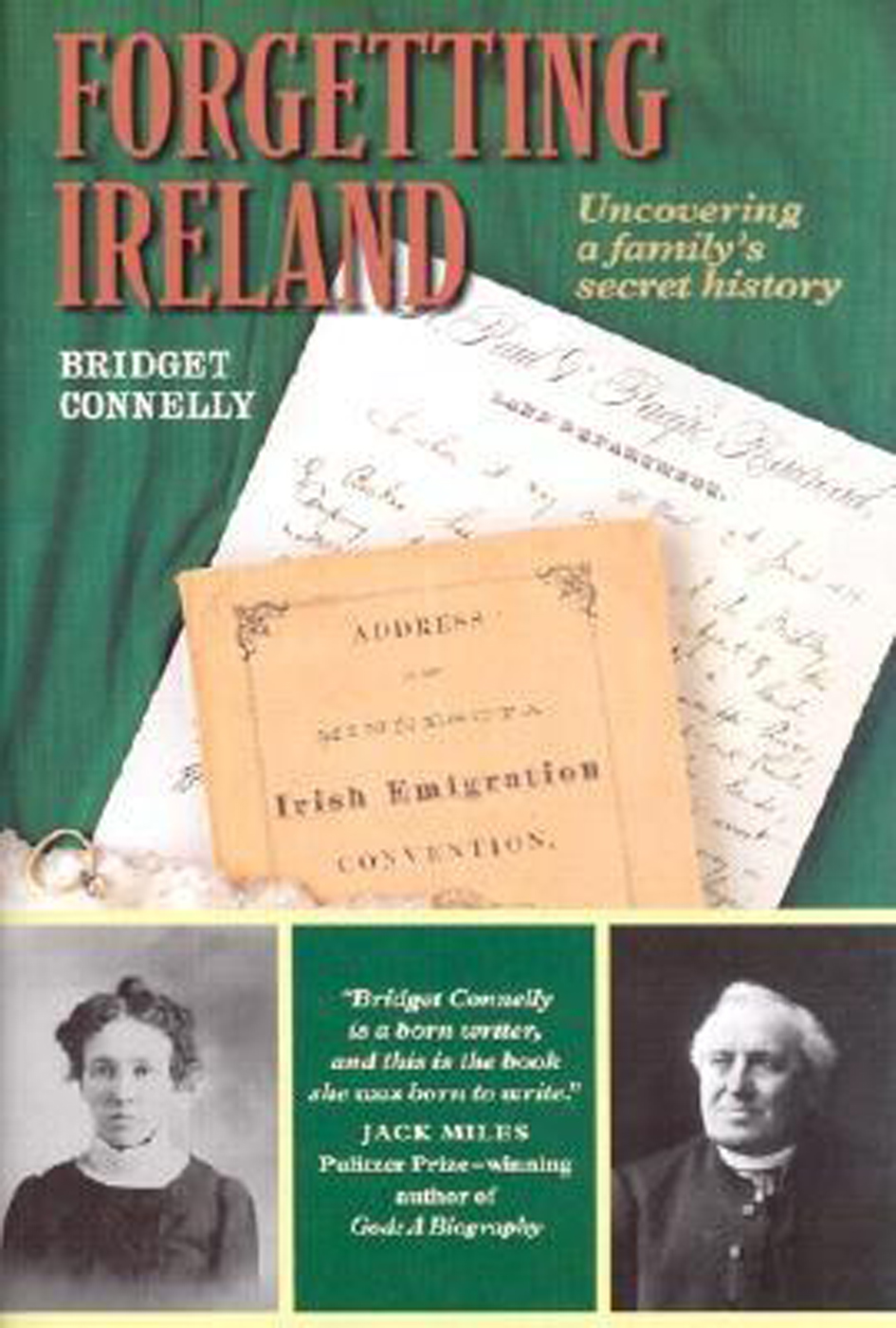

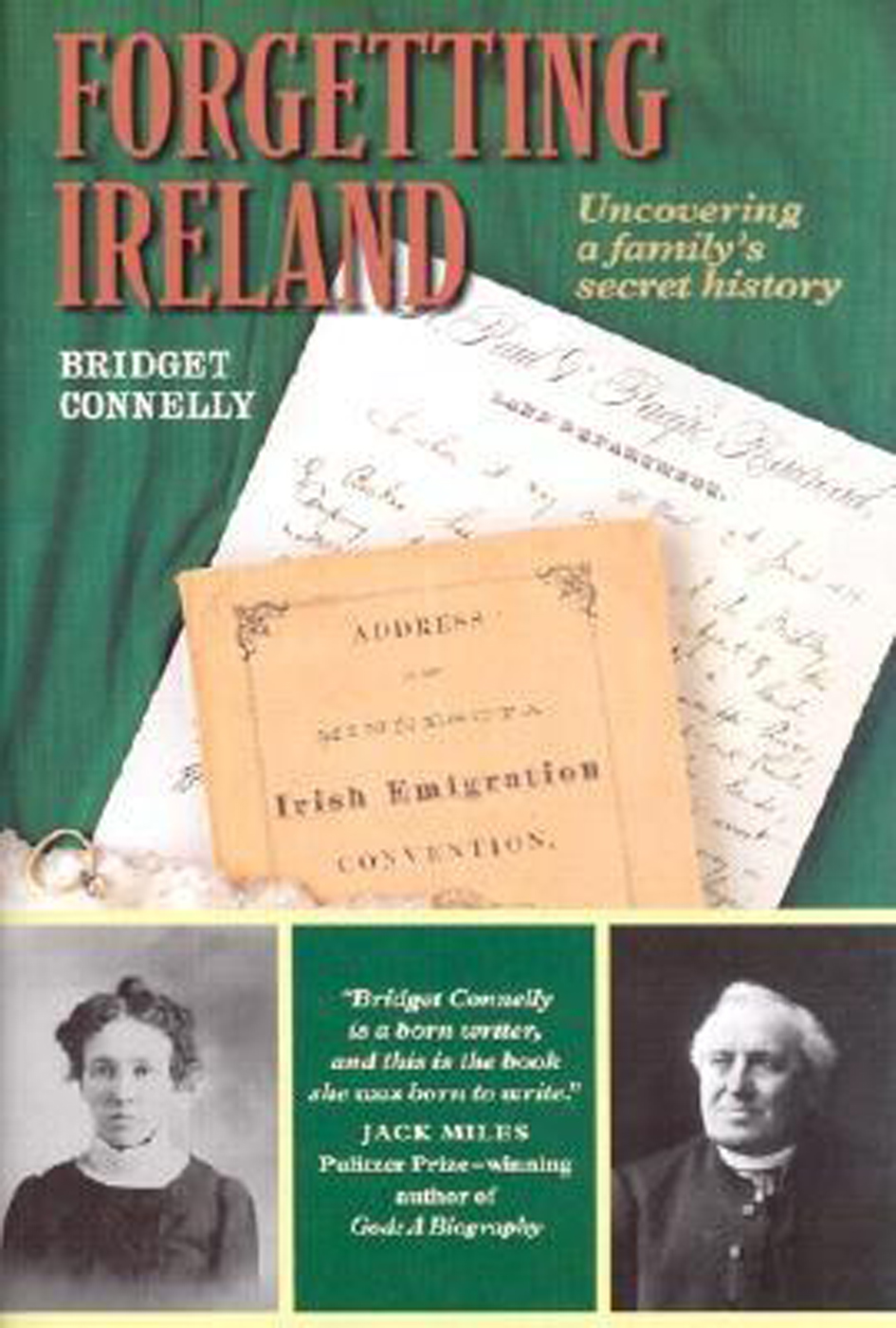

Forgetting Ireland

Bridget Connelly

FORGETTING IRELAND

Borealis Books is an imprint of the Minnesota Historical Society Press.

www.borealisbooks.org

2003 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For information, write to Borealis Books, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

International Standard Book Number

0-87351-449-1

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Connelly, Bridget.

Forgetting Ireland / Bridget Connelly.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87351-449-1

1. Irish AmericansMinnesotaHistory. 2. Irish AmericansMinnesotaBiography. 3. ImmigrantsMinnesotaHistory. 4. ImmigrantsMinnesotaBiography. 5. Flaherty family. 6. Irish AmericansMinnesotaGracevilleBiography. 7. Graceville (Minn.)Biography. 8. MinnesotaEmigration and immigrationHistory. 9. Connemara (Ireland)Emigration and immigrationHistory. I. Title.

F615.I6C66 2003

977.64320049162dc212002013548

For

KATE, CLARE, and ANNE

the great-granddaughters of the Thousand Dollar Bride

Contents

Forgetting Ireland

PROLOGUE

The Conamaras Are Coming!

This is the story, :

I T IS 1880 on the Connemara seacoast due west of GalwayIar Connacht, the poorest of Irelands provinces. Potato crops failed in 1878 and 1879. People are starving, again, as in 1846. The bottom has fallen out of the sea kelp market. Rents are unpaid, evictions rife, riots against landlords and their agents frequent.

The morning of June 11, the SS Austrian, bound from Glasgow to Boston, calls at the port of Galway. Three hundred thirty-eight people board. They are paupers, and most of them speak only Irish Gaelic. Chosen from the poorest and most pitiful charity cases along the distressed seacoast, they are bound for the far west of Minnesota, for Graceville.

Newspaper coverage on both sides of the Atlantic heralds their departure. Father Nugent of the Liverpool Relief Committee and editor of the Liverpool Catholic Times witnessed the extent of suffering along the Connemara coast on his fishing trip there in the fall of 1879. His pleas on behalf of the famine-stricken have enlisted the aid of Bishop John Ireland of Minnesota and the Catholic Colonization Bureau of St. Paul. The two clergymen have launched a charitable appeal to finance the relocation of up to fifty Connemara families to homesteads near the new Irish colony of Graceville, in Minnesota. The Irish of that state and New York have responded by donating thousands of dollars. The railroad has offered free passage from Boston to Minnesota. Father Nugent has made arrangements with local priests to select the emigrant families. The Liverpool Relief Committee and the New York Herald relief fund have contributed to the sea passage. The Allan Shipping Line has offered a special port of call in Galway to board the emigrants.

The ship sails with thirty-seven families. Irish Nationalists loudly decry this assisted emigration as an English plot to depopulate Ireland. Charles Stewart Parnell is president of the newly formed Irish National Land League, which condemns Father Nugent as an agent of landlords and the British government. It also denounces the misguided Minnesota enemies of Ireland. In June, as the Austrian sails, Parnell and another prominent Irish political leader, Michael Davitt, sign a resolution that officially and vehemently condemns the assisted emigration of the Connemara paupers.

After a pleasant crossing, the ship docks at the Cunard wharf in East Boston on the night of June 22, 1880. The next day curious crowds throng to the wharf to get a look at the much publicized Connemara colonists. The sinewy, lean people are sunburned from the sea journey. The children are poorly clad, barefooted and bareheaded, as they run up and down the dock. Old men and women sit on boxes and tattered bundles, their faces set in a pensive gloom. They are met by the secretary of the Catholic Colonization Bureau, Dillon OBrien. Over lunch that day, OBrien remarks to a friend, It does look bad, but Ill wager a new hat that before twenty years some of these same people will come to Boston dressed in broadcloth; that they put up at your best hotel and eat at the best table in the house.

At three oclock in the afternoon, the colonists board the train for St. Paul via Chicago. William J. Onahan, city collector of Chicago and Land League supporter, greets them in his city on behalf of the St. Patricks Society, which feeds them and provides clothing. The condition of the travelers pains Chicagoans. To Onahan, the pilgrims look emaciated and squalidly wretched; their features seem quaint, pinched from famine, the arms and legs of the children shriveled.

The train reaches St. Paul on Saturday, June 26. A crowd awaits the new colonists and the Celtic tongue rolls as musically in Minnesota as among the rocks of Connemara. Bishop Ireland himself meets the train to welcome the newcomers and superintends the dinner reception prepared by the ladies sodality and the Emigration Committee.

The bishop and the railroad have provided each family with 160 acres of virgin prairie lands, a cow, work implements, and crop seed. On closer inspection, a few families seem unsuitable for the rigors of Minnesota prairie farming. Two are kept in the city, another three are sent as laborers to an established bonanza farm. Bishop Ireland also settles thirty-five grown-up girls into jobs in homes as maids and forty-five boys into work as laborers. Their wages will help support their families near Graceville until next spring, when they will join them to put in the crop.

Thirty families board a special express train loaded with flour, household goods, and farming supplies. Railroad baron James J. Hill personally attends to the emigrants. They ride to the end of the line at Morris. At stops along the railway line, villagers greet the approach of the train with calls of The Conamaras are coming! The Conamaras are coming! Local settlers along the route feel invested in the future of this trainload of people. Many of them have contributed anywhere from ten cents to a munificent five dollars to the charity subscription drive that brought the famine-stricken Irish here.

Out the train window, the emigrants see green, flowering prairie that stretches endlessly flat into the encompass of a wide sky, with only a few cumulus clouds interrupting its limpid blueness. On this warm summer day, the newcomers cannot begin to imagine a prairie winter. The rainy bogs and rocky coastline they left behind in Connemara were cool the year round, seldom colder than forty-five degrees Fahrenheit, seldom warmer than seventy.

The train arrives at the end of the line in Morris, a frontier town of one thousand. Townspeople, dignitaries of the Masonic Lodge, and railroad agents all turn out to witness the most interesting event to occur since the railroad tracks arrived in 1871. Graceville parishioners and River Irish members of Morriss Assumption Catholic Church arrive with wagons to transport their new neighbors.

Next page