The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For my mother, to whom we are all linked

who would wish for a life without hope of old age, who would wish for the idea of a story in place of the story itself? But the what was meant is worthwhile, tooa short yet interesting life carries not simply intimations but constructs of the whole; and a story must not merely be , but mean.

Cynthia Ozick, from the preface to Bloodshed and Three Novellas

1 Backdrop

In January 1984, at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, my husband, Joe, and I are looking at prints of Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, by Ansel Adams. A slender young man in a suit has brought us, as requested, three versions of this famous photograph. He dons a pair of white gloves before removing the 14.5-by-18.5-inch enlargements from their Plexiglas sheaths, opens the hinged glass viewing case in front of us, and places them carefully, lovingly, on a slanted white board inside. He stands there while we examine the pictures; when we are finished, he will repeat the process in reverse.

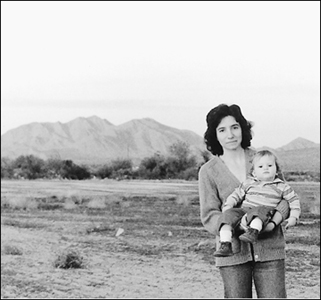

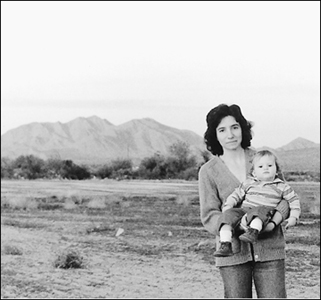

I dont know exactly where Hernandez, New Mexico, is, but it reminds me a bit of Sacaton, the Pima Indian village ninety miles northwest of here, where Joe is a government doctor and where we have lived since July of 1983. We have made the trip to Tucson today expressly to view the Ansel Adams photos, though we had not imagined that there were so many different prints of the same negative.

In Moonrise two-thirds of the space is usurped by a rich black sky; a gibbous moon floats like a hot air balloon in an otherworldlyand yet absolutely southwesternlandscape. A gauzy strip of low clouds or filtered light drifts along the horizon; distant mountains are lit by waning sun or rising moon. Only in the bottom third of the photo, among scrubby earth and sparsely scattered trees, does human settlement appear: a small collection of modest adobe houses and one large adobe church. Around the edge of the village, white crosses rise from the ground at many angles. At first glance they resemble clotheslines strung with sheets or socks, but upon examination it is obvious they mark graves.

The prints differ greatly in quality from the reproductions one usually sees, and they also differ slightly from each other: Here we see a more defined darkness, burned in by the photographer; there a variation in exposure, a grainier texture. But that does not change the essential meaning of the photograph, a meaning one never forgets in the Southwest: nature dominates. Human life is small, fragile, and finite. And yet, still, beautiful.

* * *

I didnt want to move to Arizona, but Joe had obligations. The government had paid his medical school expenses, and in return he promised to work for three years. An anthropology major at Columbia, he had his heart set on working with Native Americans. This job gave him his chance.

It was July when we left our apartment in Manhattan and drove cross-country to Sacaton, the center of the Gila River Indian Reservation. It was a tumbled, tangled, green-gray land, flat and arid, shadowed by barren purple hills. The scattered houses were wood-and-earth or stucco, painted in pastels. Here and there a flash of bright yellow flowers lit the landscape, or a bold saguaro stood. It was as hot as Jerusalem.

The town was not much more than this: a Chevron station, a post office, a Valley National Bank, a grocery, an auto parts store, tribal buildings, and a restaurant, the Sandwich House. We had no library and no park, no movie theater, and no supermarket. Unlike Joe, who worked at the twenty-threebed hospital, I had no task and no colleagues. I had no child. I was stranded.

We lived on the hospital compound in a government-issue, green-stucco ranch house with linoleum floors and a large square yard bordered by oleander, mountains out our back window. It wasnt paradise, but it was an oasis, where mulberry and pomegranate trees grew and where the ever-present glow of the emergency-room light seemed to protect us from the rough and alien life of the reservation.

My thoughts were of loneliness and heat, of grass the color and texture of straw; of the garden hose in my backyard, cracked and coiled like a hardened rattlesnake, of black widow spiders nesting in the garage, of the minitornadoes they called dust devils, and of water so hard it left a green coppery crust; you had to scrub it off the bathroom tiles and the plug in the sink.

The first week I dreamed I was running down the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens, close to where I was born, in a purple bathing suit my youngest sister, Mimi, had knitted for me. It was ill fitting, a size too big. I jogged; it was pouring. I had twenty-five miles to go. I couldnt find my way home, no matter how much I ran. Every street was a blind alley.

By day I sat at my desk in the little front room of the house, forcing myself to write something, at least a paragraph about my new life in this difficult, cryptic territory. I sought control through language, the handholds of grammar, trying to put names to flowers and streets, constructing sentences and paragraphs. I learned the words creosote and medevac; I learned about the local gangs, the Snakes and tbe Chollas, named after a sharp, bristly cactus that easily took root. This was a new world, and for a long time it was a withholding world whose underside was wildness and rage. The summer sky, so still and unflinchingly blue in the morning hours, slowly and insidiously disappeared by evening, giving way to black clouds of dust, to storms that screamed across the valley and sent the tumbleweed spinning and collecting debris, storms that tore the shingles off houses and knocked down telephone poles, sending us into darkness and scrambling for the tiny flame of a Coleman lantern. We lit it and sat, waiting for clarity.

* * *

In September the Gila and Salt Rivers flooded. People called it the hundred-year flood, the most rain in generations. We were in Denver at a medical conference when it began. I left Friday morning after a job interview, in drizzle, to meet Joe, who was already in Colorado. We spent a blithe weekend, unaware of the floodwaters sending Arizona into a state of disaster. By the time we returned on Sunday, the Salt River, which runs through Phoenix, was so high we couldnt drive home by way of the Hohokam Expressway, the route to the south, our usual path to the interstate. Instead we had to head north to Buckeye Road, and skirt the unbridged crossings of the Salt.

By the time evening came, flooding all over the state had worsened. Stories about Clifton, halfway under water, began to reach us. Downstream, the Gila was causing havoc. For the first time since wed been in Arizona, there was actually water in the river.

Monday morning I had an appointment in Tempe. Though more and more road closings had been announced, I-10 was still open. I set out at about 11 A.M. planning to eat lunch there, keep my date, and drive home. About ten minutes later, I crossed the Gila on the interstate. Several public-safety and police cars were parked on the bridge. I stopped and looked down. The water was rushing forcefully, touching the undersurface of the bridge. I hurried to the next exit, turned around, and drove home.