Wicked

AKRON

Wicked

AKRON

TALES OF RUMRUNNERS, MOBSTERS

AND OTHER RUBBER CITY ROGUES

KYMBERLI HAGELBERG

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Kymberli Hagelberg

All rights reserved

First published 2010

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.062.5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hagelberg, Kymberli.

Wicked Akron : tales of rumrunners, mobsters, and other Rubber City rogues / Kymberli

Hagelberg.

p. cm.

print edition: ISBN 978-1-59629-915-3

1. Crime--Ohio--Akron--History--Anecdotes. 2. Violence--Ohio--Akron--History--Anecdotes. 3. Corruption--Ohio--Akson--History--Anecdotes. 4. Criminals--Ohio--Akron--Biography--Anecdotes. 5. Rogues and vagabonds--Ohio--Akron--Biography--Anecdotes. 6. Akron (Ohio)--History--Anecdotes. 7. Akron (Ohio)--Social conditions--Anecdotes. 8. Akron (Ohio)--Biography--Anecdotes. I. Title.

HV6795.A32H2 2010

364.1092277136--dc22

2010041013

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The events depicted in Wicked Akron were researched from existing public records and historical and news accounts. The book was completed with invaluable assistance from historical societies throughout Summit County, the AkronSummit County and Barberton public libraries, the staff and editors of the Akron Beacon Journal and sources throughout northeast Ohiowicked and otherwisewho generously shared their knowledge and memories. Love and thanks also to Raj, the best partner and researcher ever, and to Jinny Marting for her sharp eye, long friendship and freshman composition.

PART I

EARLY AKRON

Think of it as the Wild West.

Until 1803, the length of the Cuyahoga River between Akron and Cleveland was the western boundary of the United States. The city of Akron wouldnt exist for another generation, Summit County was nearly forty years in the future and Portage Path was part of an Indian reservation.

Settlers fought the land, insects, disease and isolation to live on the fringe of early nineteenth-century society in Portage Township, the rugged frontier of the Connecticut Western Reserve. Aspirin, antibiotics and matches were all a century away from wide use. Those first residents generally lived in one-room cabins built on hand-cleared, heavily forested land with deep swamps and streams left over from the Ice Age. Roads were where you or your predecessorstrappers and sometimes squatters on your landdug them. Keeping a fire stoked was a life-and-death endeavor. Settlers who failed the task found themselves traveling miles with a shovel in hand hoping to return home with hot coals provided by a generous neighbor.

In what is now East Akron, business took off in a village called Middlebury. By 1815, Middlebury was a commercial center of four hundred hardworking, hard-living men, women and children. Residents worked at the nail factory, gristmill or ironworks and could shop at about a dozen stores. Historian Karl Grismer described Middlebury as a lusty town and Middleburians as enthusiastic customers of three village taverns, which also served as stagecoach stops, hotels and houses of entertainment for men and beast of a rather primitive character.

Though it became one of northeast Ohios biggest industrial centers, by 1825 Middleburys fall was imminent. Like most cities in the Western Reserve, Middlebury lacked a reliable way to export its products to the rest of the country and so was short of the cash that working people needed to pay their debts and taxes.

An unlikely, some said fantastic, solution was found in the construction of the Ohio & Erie Canal. It was a risk on which Simon Perkins built the city of Akron that we know today, and where the tales of Wicked Akron begin.

KILLER FOG

PLAGUE ON THE OHIO CANAL

The Ohio & Erie Canal was the engineering marvel of its day and saved the states economy at a time when transporting goods to market meant navigating through unpopulated and sometimes uninhabitable areas. About three thousand canal diggers worked on Ohios 309-mile project. The majority were canal diggers who originally came from New York to work on the Erie Canal. The rest were poor boys from the Western Reserve and Irish and German immigrants.

In 1827, hundreds of them are said to have perished when a plague took hold at Summit Lake that left the fledgling city of Akron a ghost town and spread as far north as Peninsula and Boston Heights. Workers blamed a killer fog that rolled off the lake into their tents and canal-side shanties for the black tongue fever that swept the camp at night. So many were wiped out in the epidemic that a saying from the time is still common among towpath tour guides today: Theres a dead Irishman for every mile of the Ohio & Erie Canal.

The acrid fumes that canal workers feared likely came from the methane created by fish and vegetation left to rot when Summit Lake was lowered for the canalsmelly, but not fatal. However, the decomposition did draw insects and contaminate the water, causing cholera, malaria and typhus up and down the canal. Nearly identical tales of epidemics are told about work on the Erie, Pennsylvania & Ohio and the southern leg of the Ohio & Erie canals.

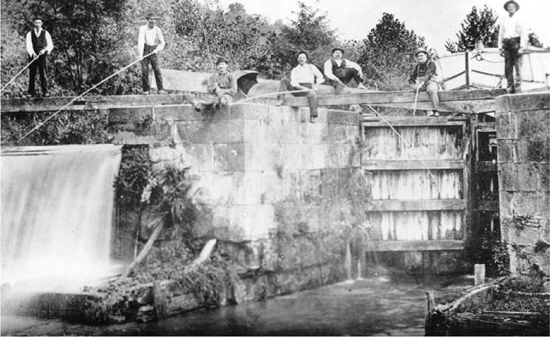

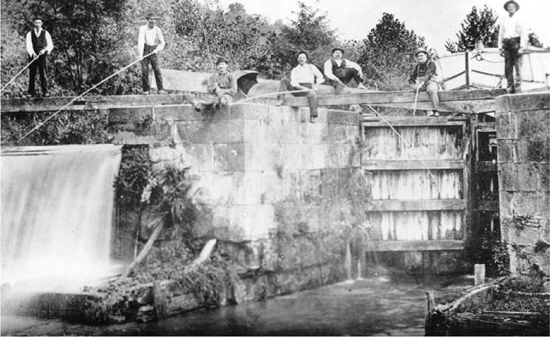

Men fishing at Lock 1 in Akron. Workers cleared 230,000 cubic yards of mud, rock and thick vegetation to build the Akron leg of the canal. AkronSummit County Library.

The sicknesses continued to spread in the summer of 1827 after the Fourth of July grand opening of the Akron to Cleveland leg of the canal. Workers lost to death and illness caused delay after delay on the completion of the portion of the canal between Summit Lake and Stark County.

Modern physicians credit the outbreaks to the lack of sanitation, poor nutrition and immune systems lowered by grueling labor. Workers soaked to the waist dug in the muck with picks and shovels to lower the lake by nine feet, whether temperatures sweltered or neared freezing. Other workers hauled heavy blocks of stone into the lake to form the locks or hacked away through heavy swamps clogged with spiny tamarack trees that cut their flesh. Building the canal by hand was a monumental task accomplished by workers who were underpaid, malnourished and often very ill. One Canal Commission report notes that 230,000 cubic yards of muck were removed to dredge a channel through the swamp at Summit Lake, then called Summit Pond. Workers wore tin smudge pots called Montezumas necklace to repel swarms of biting black flies and mosquitoes. The smoldering rocks and leaves that burned in the pots workers wore around their necks created a fog that kept the bugs away but left behind scars that ringed the workers necks for the rest of their days. Canal diggers worked from dawn to dusk and were paid pennies a day, plus a loaf of bread, a ration of too-often rotted meat and generous amounts of whiskey.

Next page