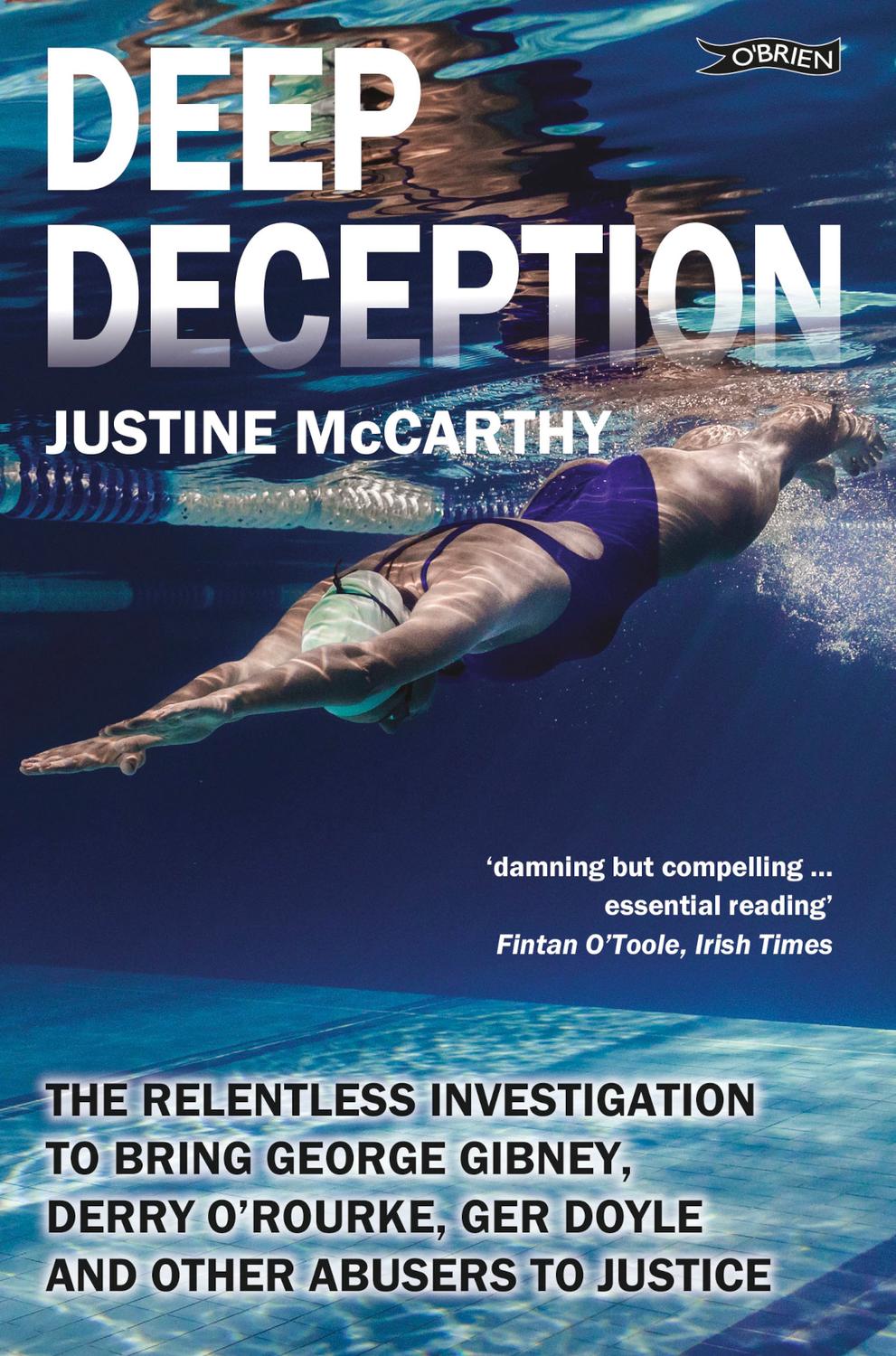

Damning but compelling essential reading the best of the large crop of books by Irish journalists this year, it grows beyond its immediate subject to become a terrifying anatomy of the capacity for denial and vilification within any enclosed world

Fintan OToole, The Irish Times

Very compellingly written.

Pat Kenny, RTE Radio 1

This is a story that needed to be written. All the victims have ever asked for is justice and for people to know what happened. Now, thanks to Justine McCarthy, they do.

The Irish Times

Mandatory reading for every parent.

Joe Duffy, Liveline, RTE Radio 1

Heartrending. Sunday Tribune

Hard-hitting. Irish Daily Star Sunday

Bristles with anger, glows with compassion and asks some difficult questions a thoroughly researched and readable work.

Sunday Tribune

Contents

Two Mexican boys drift by on the current

In a dead-mans float, shirtless, their bodies

Dark as skates. Just as they pass,

They roll over onto their backs

Laughing before they hit the spot where the rapids

Begin to wheel and surf out of sight.

(From the poem, Flood, by Brian Barker)

The dead mans float is a survival technique recommended to swimmers. The swimmer is required to adopt a vertical position in the water, face down with only the back of the head breaching the surface. The swimmer allows his or her arms and legs to dangle and raises his or her head regularly to breathe in oxygen. It is the air in the lungs that keeps the swimmer afloat. Although the name is derived from the common position in which human corpses are found in water, the technique is recognised as a method of prolonging endurance. The smaller the swimmers limbs a childs, for instance the more likely the person is to float facing upwards, and to survive.

I was a staff features writer for the Irish Independent in the mid-1990s when I was drawn to a story that was to occupy my life for years to come the story of the sexual abuse of children within Irish swimming. At that time, I knew Chalkie White only by his newspaper byline as he was the Irish Independents swimming correspondent. Our paths did not cross until he sought me out in the office one night with the quintessential journalists bait: Ive got a story for you thats going to be massive when it breaks, he promised, or words to that effect.

The names Derry ORourke, George Gibney and Frank McCann are now notorious, but this was still two years before Derry ORourke would be jailed for the first time for sex offences involving child and teenage swimmers. George Gibney had fled the state after charges against him of indecent assault and unlawful carnal knowledge of young swimmers collapsed on a technicality. Frank McCann was in jail awaiting trial for the murder of his wife and foster daughter. At that stage, the macabre events tearing swimming apart were still the sports dirty little secret. A secret that Chalkie White was determined to expose.

Chalkie would collect me in his car at night after we had both finished work; it was on these night-time excursions that he introduced me to survivors of child sexual abuse in the sport of swimming. Through him I first met the swimmer whom George Gibney had locked into a Florida hotel room and raped five years before. Two years before the night we were introduced, she had made her first attempt to kill herself, but she was clinging to life and for the purpose of our meeting to her anonymity in her suburban home, flanked by her loving parents. She talked with machine-like detachment, as if her mind had managed to disengage even if she could not make her body stop living.

Despite the enforced silence of the survivors or possibly, because of it there is an enduring esprit de corps between survivors of George Gibney and survivors of Derry ORourke. Many of them had been elite swimmers whose lives overlapped in the pool. It was Chalkie, on his mission to expose George Gibney, who introduced me to Bart Nolan, the doughtiest pursuer of justice you could hope to meet. Through Bart, I came to know eight of the women who had been abused by Derry ORourke. On every encounter over the years, my admiration for their dignity and strength of character has been renewed. I feel they are my friends.

The people whose stories have combined to create this book had their voices taken from them as children. By telling their stories, they are taking their voices back. Those abused by George Gibney, Derry ORourke and Fr Ronald Bennett were warned to say nothing. They grew up saying nothing. Their friends, their neighbours, their extended families and work colleagues have never known about the childhood torments that haunt them. In some cases, their parents went to their graves still oblivious. Though most of them, apart from Chalkie White, Lorraine Kennedy and Karen Leach, remain anonymous, they are men and women of singular fortitude and I thank them for their courage.

In the early days, when the survivors were unable to speak even off the record, others spoke for them. Gary OToole, the world-beating swimmer, has been an even greater champion behind the scenes than he was in the water. He took personal risks beyond the normal human obligations to ensure that good eventually triumphed. Were it not for Gary, his father, Aidan, and his mother, Kaye, these tragedies might have been brushed under the carpet. Another hero is Johnny Watterson, now a sports journalist with The Irish Times, who, along with a plucky editor and a dash of pragmatic legal advice, exploded the taboo of naming George Gibney as a child sexual abuser in the Sunday Tribune after the States criminal justice system failed to do so.

These people have been invaluable sources of information to me, contributing by way of interviews, correspondence, photographs and a wealth of documents. Because so many cannot be named, it has not been consistently possible to identify sources of specific information throughout the narrative. Others, such as Carole Walsh, who privately advocated on behalf of two of George Gibneys victims, have been wholeheartedly committed to ensuring the story is told. Marian Leonard, the sister of Esther McCann, who was murdered along with her beloved little Jessica by Frank McCann, has tirelessly told and re-told her story so that it can reach the widest possible audience. I thank Marian and her daughter named Esther in honour of her aunt for all their help and for their bravery.

Val White was one of the many indirect victims of the secret crimes in swimming. I thank her especially for her courage in telling how her marriage to a man she loves to this day disintegrated under the strain of Gibneys legacy.

When Michael OBrien of The OBrien Press initially approached me to write a book on child abuse in swimming I had reservations; I was concerned that the book would become just another true crime book, dependent on shock value. But when I ran the idea by some of the survivors, they unanimously decided that the book had to be written, for all sorts of reasons: catharsis, truth, vindication, but most of all to safeguard the children of future generations. For more than two years, they willed this book on, figuratively sitting on my shoulder and tapping the keys of this laptop. When we hit wall after wall, the text messages, emails, phone calls and catch-up cups of coffee with Karen, and swimmers A, B, C, D, Bart and Aidan et al kept the momentum going. Weve toasted a wedding, a new baby and a class action High Court settlement in the lacunae.

And so I, along with the survivors of these swimming scandals, want to say thank-you, finally, to The OBrien Press for treating the story of their lives with sensitivity.