A

LINE

IN THE

WORLD

A Year on the North Sea Coast

-

DORTHE

NORS

Translated from the Danish

by Caroline Waight

Illustrated by Signe Parkins

GRAYWOLF PRESS

Copyright 2021 by Dorthe Nors

English translation copyright 2022 by Caroline Waight

A Line in the World was first published as En linge i verden by Gads Forlag in Denmark, in 2021

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. Significant support has also been provided by the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

212 Third Avenue North, Suite 485

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64445-209-7 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-64445-192-2 (ebook)

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2022

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022930640

Cover design: Kyle G. Hunter

Cover and interior illustrations: Signe Parker

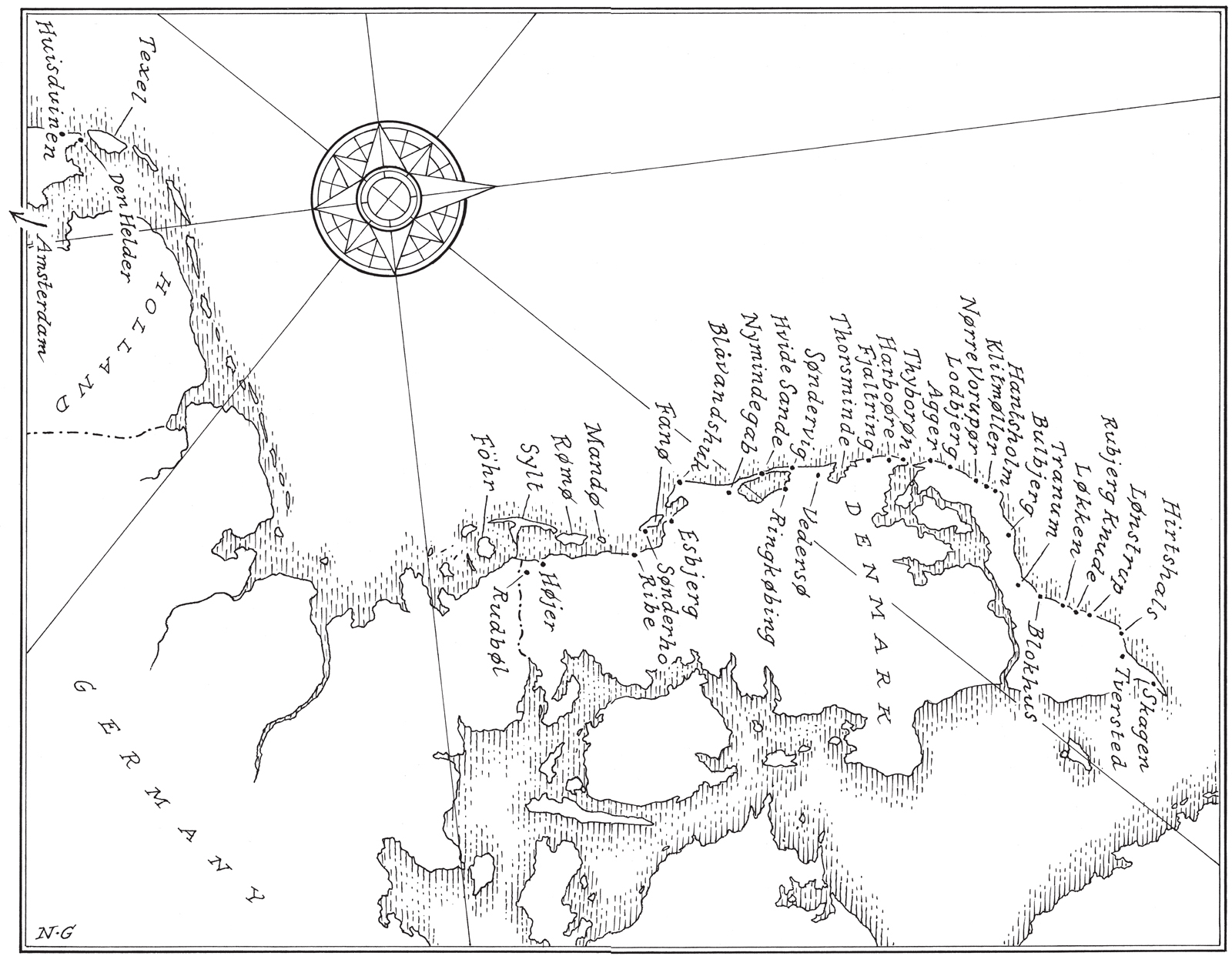

Map: Neil Gower

The Line

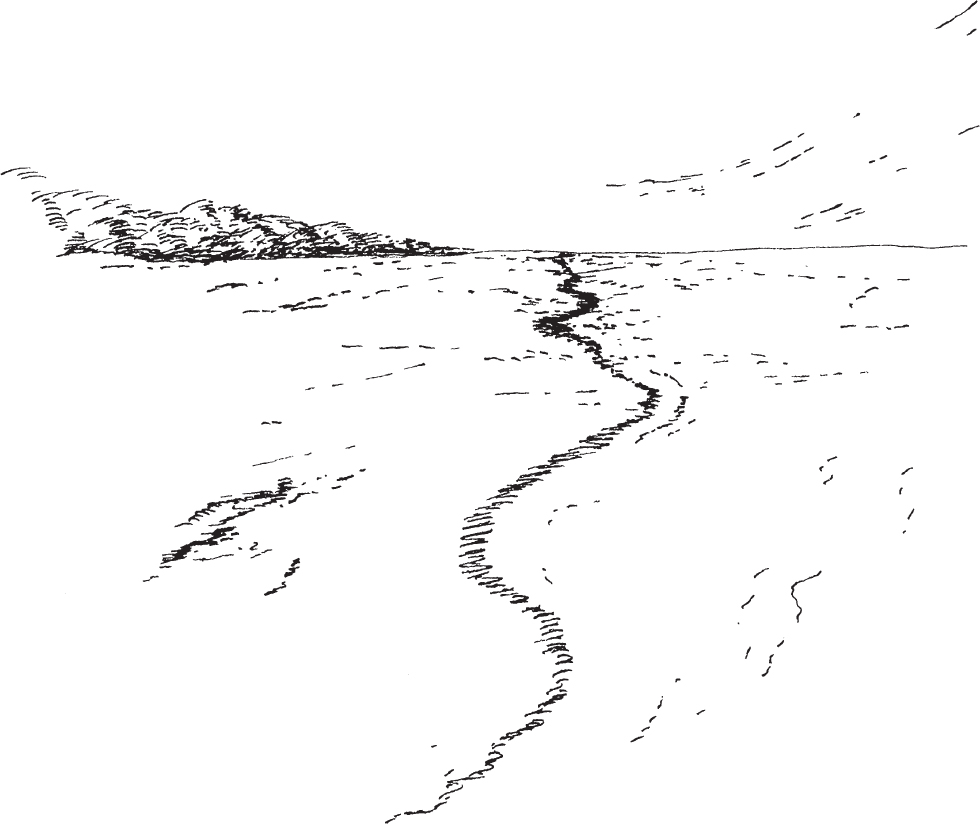

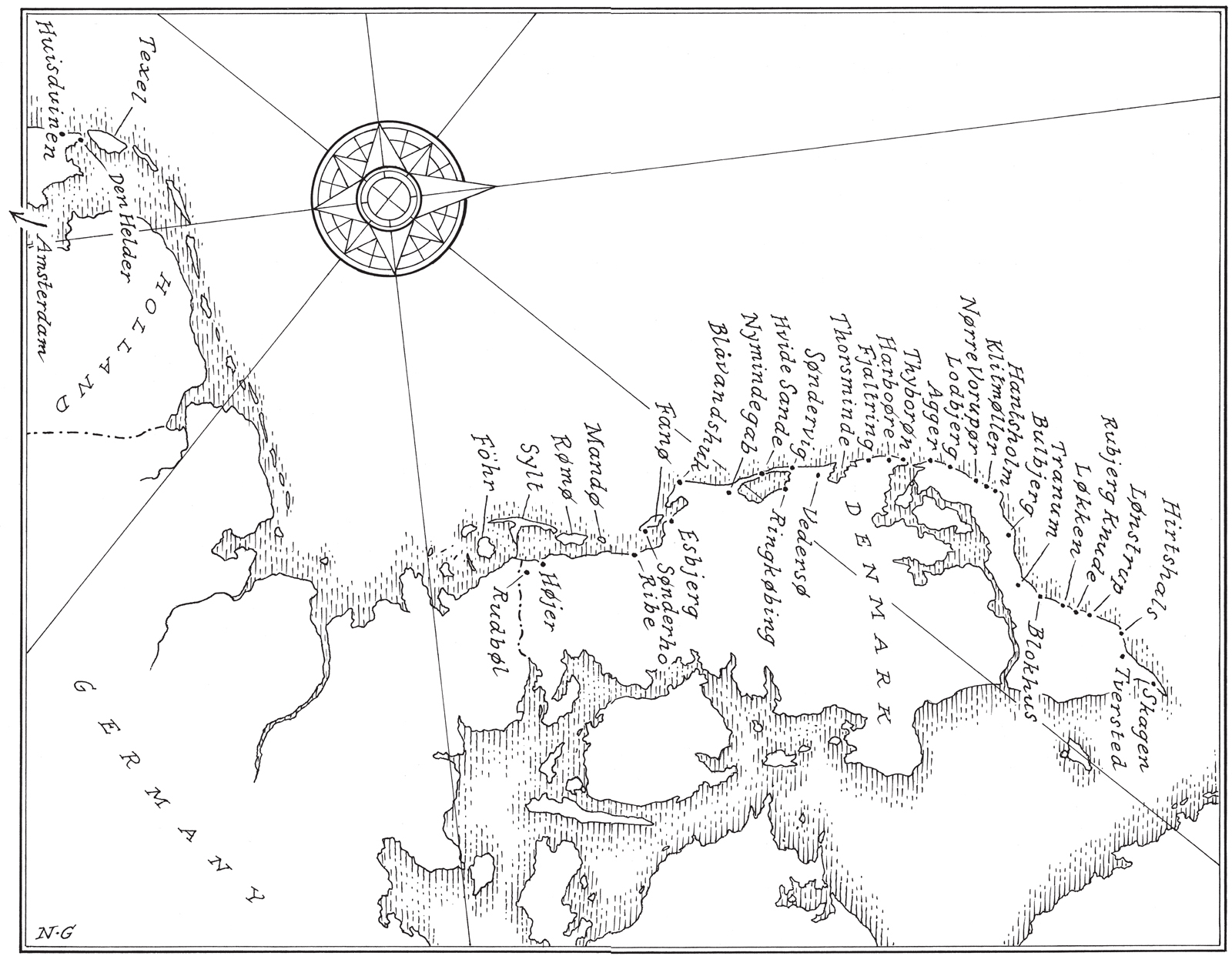

Its early summer and far beneath me is a coastline. I have it folded out, a map on my desk. It begins to emerge at the northernmost tip of Jutland in Denmark. Yes, thats where it begins, in the North Sea, on a tapering spit of sandy ground. Then it drops south like a slope. It meanders downwards. Now it has begun, the line. It charts a coast and continues, curving faintly outwards. Then come the cervical vertebrae. They settle one by one, stacked each on top of another, sandy islands. And the line persists, breaking borders, into Germany and on. The islands settle like smaller delicate vertebrae into Holland, now charting not a line but a living being.

A rugged Northern European coastline of roughly 600 miles, from Skagen in Denmark to Den Helder in Holland. From a northern sandy spit wedging itself between Norway and Swedens unyielding massifs down to the Wadden Sea, where the birds take rest, the hours are counted and the living being whispers.

The line has been a part of me since the beginning. Physically, but on large maps in classrooms too, on television, in the AZ in my parents car. Seen in context with the rest of the country, it looks like the back of a dozy Jutlander with a silly cap and big nose, facing east. Always read from top to bottom, from left to right. Never turned on its head, fragmented, joined or transgressional. On the map beneath me, the land lies as it lies. A distant coast. Unfamiliar and raw, considered from a centre of power. At one time there were scarcely any roads across the broad heaths of the Jutland peninsula to the shores of the North Sea, and there were no bridges between Denmarks countless islands, large and small: the land was matted, impenetrable. But today the distance between this border and its faraway metropolises is largely psychological. There are roads into the system now, bridges over the water, airports and civilized infrastructure. The land coheres, and now its spread on the desk beneath me, fixed by a map-maker.

But if I could do what I wanted with time, if I could accelerate it like a piece of time-lapse footage where the roses turn from bud to blossom, the line would be alive. The drawing would always be moving. It would bend forwards, shift backwards, open, turn, perforate; then close, then open up again. It would vanish in part beneath heavy masses of ice but be revived as something else, and it would dance, its tail one moment twisting like an eel, fluttering the next like a pennant. It is a living coastline made of sand. Always becoming, always dying. Determined by the forces of the galaxy streaming through the universe, marked by the storms, the wandering of the sun and moon, and human intervention (although the latter is always shortlived), the coastline has all the time in the world. It is a long and living tale of tidal waters, subject to the rhythms of day and night, but, in its reckoning of time, to be considered an eternity.

One line in the world. Just one. It could have been elsewhere and known other experiences, other dramas and silent reflections. What might the line from Utqiavik, Alaska to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico have to tell? Myriads. Or the line from Gibraltar to the Cape of Good Hope? There are no borders to the stories told along a line. But a landscape is beyond the telling, like the telling is beyond itself. It takes a person to take up the line somewhere, to open, look and make a cut. This coming year itll be me, gently guiding the scalpel as I write.

At first I didnt want to. I was supposed to be starting a novel. Then I was approached to write a book about the west coast of Denmark. I said no. They asked me again. And again. I said, Ill have to think it over, and I did. Or I dreamt. In the dream, I was setting off across the landscape in my little Toyota. I saw myself escaping several years of pressure from the media by driving up and down the coast. Me, my notebook and my love of the wild and desolate. I wanted to do the opposite of what was expected of me. Its a recurring pattern in my life. An instinct.

My own geography began in a suburb of Herning, Denmarks answer to Denver, Colorado or Manchester, England. A young, imaginative, knocked-together provincial town in the middle of the Jutish heath. When I was four, my family moved five miles west. My parents bought a tumbledown farm in the large parish of Sinding-rre. One half of the parish: green, lush, hilly. The other half: vast stretches of heath and forest beneath a kind of prairie sky, and from the moment I dared to move from place to place of my own accord, I went walking in the landscape. That parish is the only place on Earth where I know all the shortcuts, all the paths, and I know who lived in which house and whose children were whose. I know all the family names on the gravestones. When I come to die, that is where you should bury me.