Contents

In memoriam

Jean Freeman

and

Dr Harold Wilke

No one can write a book like this without good and kind helpers. Thus I owe my thanks to many persons.

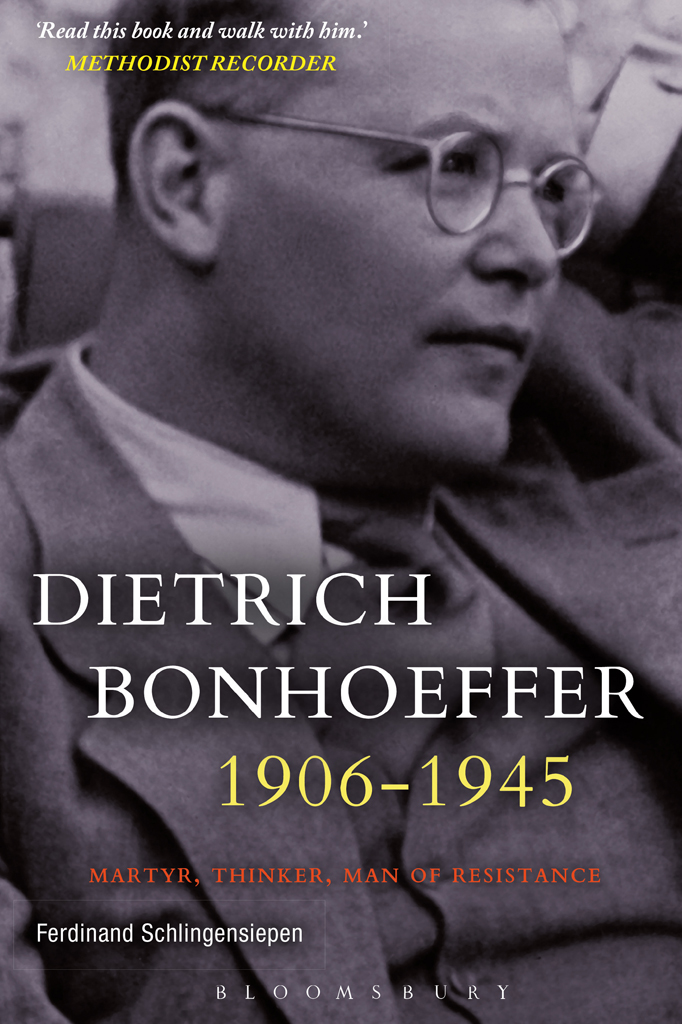

Professor Andreas Dre kindly allowed me to quote passages from the unpublished memoirs of his mother, who was Dietrich Bonhoeffers youngest sister. These memoirs provide such a lively picture of childhood and youth in the Bonhoeffer home that they really ought to be published. I thank Peter von Wedemeyer for a photo of his sister Maria (p. 335). With Ruth-Alice von Bismarck, ne von Wedemeyer, I was able to have a long conversation about her sister, whom I myself had met in 1976.

Several friends from the International Bonhoeffer Society read my manuscript or parts of it; I am thus indebted to Dr Ilse Tdt, Dr Christian Gremmels, Dr Jrgen Henkys, Martin Hneke and Enno Obendiek for important suggestions and indications. The same is true for my friends Dr Rudolf Kreis, Dr Rainer Oechslen and Dr Jrgen Regul. To Dr Ekkehard Klausa of the Memorial to the German Resistance, and Peter Schnemann of the German Academy for Language and Poetry, I also owe thanks for their critical reading of the manuscript.

My warm thanks to two graduate students, Laura Cyron and Christine Hubenthal, who, after reading parts of the manuscript, asked to see the rest and declared that the biography was quite understandable and Bonhoeffer an important subject. Laura Cyron is now writing a thesis about him.

Without the friendship of Eberhard and Renate Bethge, which I have enjoyed for over fifty years, I would hardly have been likely to write this book. I also remember with gratitude conversations about the church struggle with my father, Confessing Church pastor Hermann Schlingensiepen, and with Bishop Kurt Scharf on whose staff I served for 10 years. My wife Elisabeth and our daughters Stephanie and Irmela have offered criticisms of my manuscript which ensured that I was always brought back to the necessary objectivity about my subject. Elisabeth also proofread each new version of the manuscript.

My sincere thanks go also to my lector, Dr Ulrich Nolte, as well as Angelika von der Lahr at Verlag C. H. Beck, for their patient and knowledgeable fostering of my work.

A project such as this biography is like climbing a mountain. Towards the end, as the publishers deadline approaches, it becomes ever steeper. But long before reaching this final phase, I had found in Dr Ulrich Kabitz a mountain guide who led me onward with an energy that belied his then 85 years. Decades ago he had also accompanied Eberhard Bethge in the writing of his Bonhoeffer biography; thus he had already been the guide on the first ascent. I remember the day when Eberhard Bethge gave me a copy of his biography, with the words I dont know what Id have done without Ulrich Kabitz!

For me, Kabitz was the friend who not only carefully read every new version of my manuscript, but also drew my attention to important bibliographical sources, kept me from misinterpretations and urged me to expand the most central points in the story. As the deadline neared and it was in fact getting harder, he telephoned almost daily to encourage and advise me. I shall never forget how he once said, My wife finds your new chapter exciting and well written, but I think there are a few things you should change. In other words: Please write this chapter over again!

Ulrich Kabitz and I had become friends years earlier through our common interest in Bonhoeffer. But the guidance he provided through his knowledge of Bonhoeffers works, the secondary literature and especially the Nazi period, of which he had been an alert witness, went far beyond what one expects from a friend. So I, too, now say, I dont know what I should have done without Ulrich Kabitz. To him above all I owe my heartfelt thanks.

I first heard the name Dietrich Bonhoeffer in 1948, when I was given the small volume Zeugnis eines Boten (Testimony of a Messenger), edited by W. A. Visser t Hooft of the Netherlands, the first General Secretary of the World Council of Churches. Fascinatingly, it brought the man to life. Still, it never occurred to me to ask my father about Bonhoeffer. Years later I learned that my father had not only known him, but had once travelled in a police van with him, spending the time in animated conversation, after being arrested together with other pastors at Martin Niemllers home. Throughout my time at university, Bonhoeffer remained for me a name from the time of the church struggle, to be mentioned respectfully along with the names of Paul Schneider, Lutz Steil, Werner Sylten, Friedrich Weissler and Friedrich Justus Perels, pastors and staff members of the Confessing Church who also were murdered by the SS in their concentration camps.

In 1952 Bonhoeffers image changed almost overnight, when his letters from prison were published under the title Widerstand und Ergebung (Resistance and Submission published in English a year later as Letters and Papers from Prison) and became the topic of conversation among us younger people. The generation ahead of us were probably no less fascinated, but almost all older theologians to whom we mentioned the book found Bonhoeffers new theological ideas too fragmentary and therefore impossible to evaluate. They had experienced much of the church struggle too, but the period of the the Second World War, which for Bonhoeffer ended in death, had been entirely different for them. His new theology must have appeared utterly strange and alien to them.

I feel fortunate to this day that in 1954 I was sent to Bradford, in the north of England, to serve as pastor to a German-speaking congregation, because that was how I came to know Eberhard Bethge, close friend of Bonhoeffers and and his first biographer. He was working in London then, and in spite of the distance, we saw each other often and I was soon included in Eberhard and Renate Bethges circle of friends. I knew about Bethges laborious efforts to decipher the manuscripts of his friend in order to prepare them for publication. He was probably already working on the biography; but he was generous to any theologian who wanted to write about Bonhoeffer. He would photocopy texts, advise visitors in long conversations and provide hospitality to them. So the first researchers on Bonhoeffer came to see him through the eyes of Eberhard Bethge. This was true for me too.

To this day, most of what we know about Bonhoeffer stems from Bethges long biography of him which was published in 1967 (the English edition appeared in 1970). All subsequent biographies, including the present one, have to build on it. Since Bethge was at his friends side throughout the decisive years, his work is one of the most important sources on Bonhoeffers life. It is all the more admirable that Bethge was nevertheless able to distance himself from his subject as every biographer must.

Eberhard Bethge was convinced that, at 1080 pages, the biography was far too long for most readers. He asked me back then if I would like to write a shortened version. I set to work eagerly, but had to stop when I accepted a new position in 1969. It is only now, in the book that lies before you, that I feel I have finally fulfilled the request of the man whose friendship has meant so much to me. A shortened version of Bethges work would now no longer meet the need for an up-to-date biography of Bonhoeffer. Bethge himself, in his foreword to the fifth edition of his book in 1983, asked whether it wasnt time to revise the image that was set in 1967. This question has become ever more valid since then.