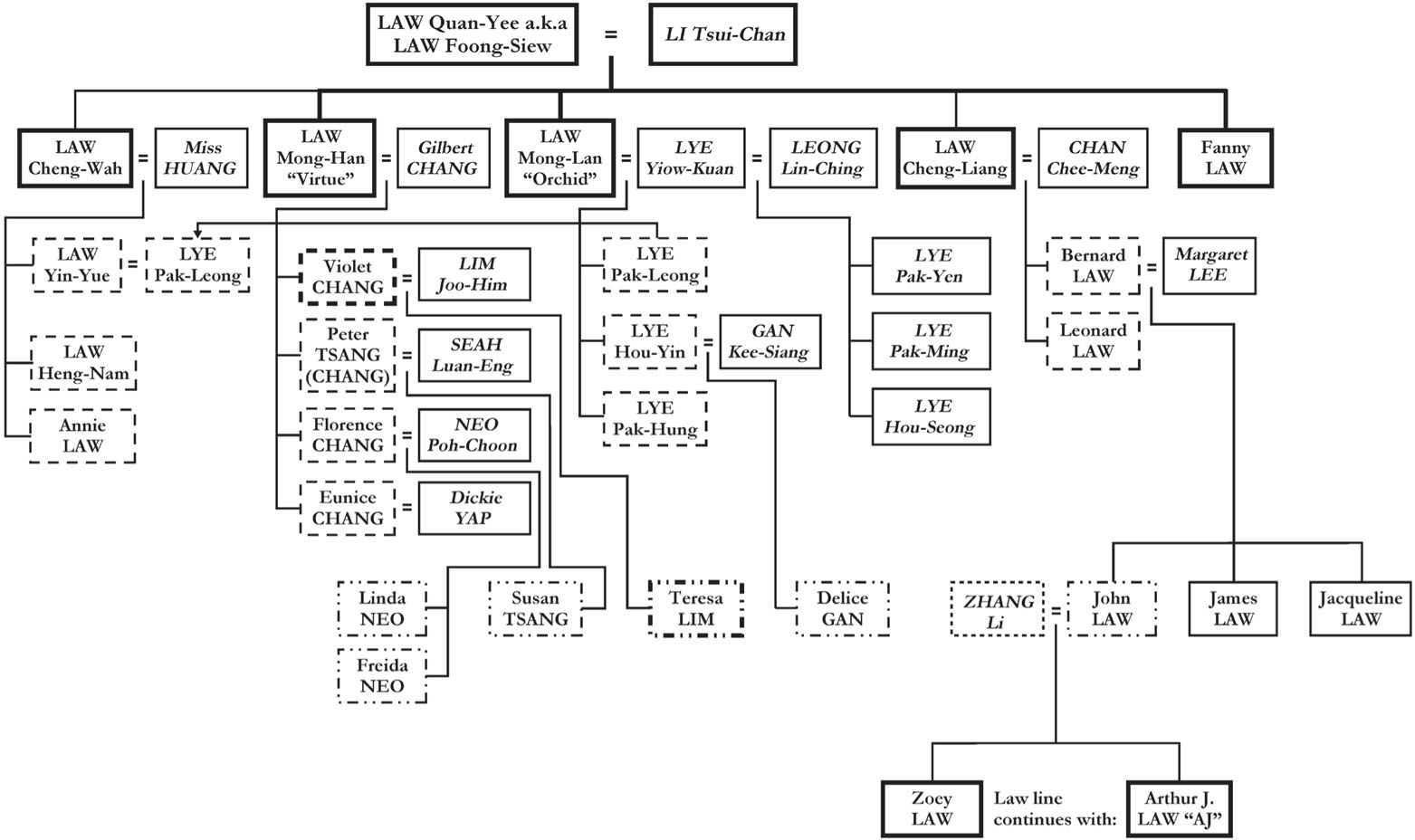

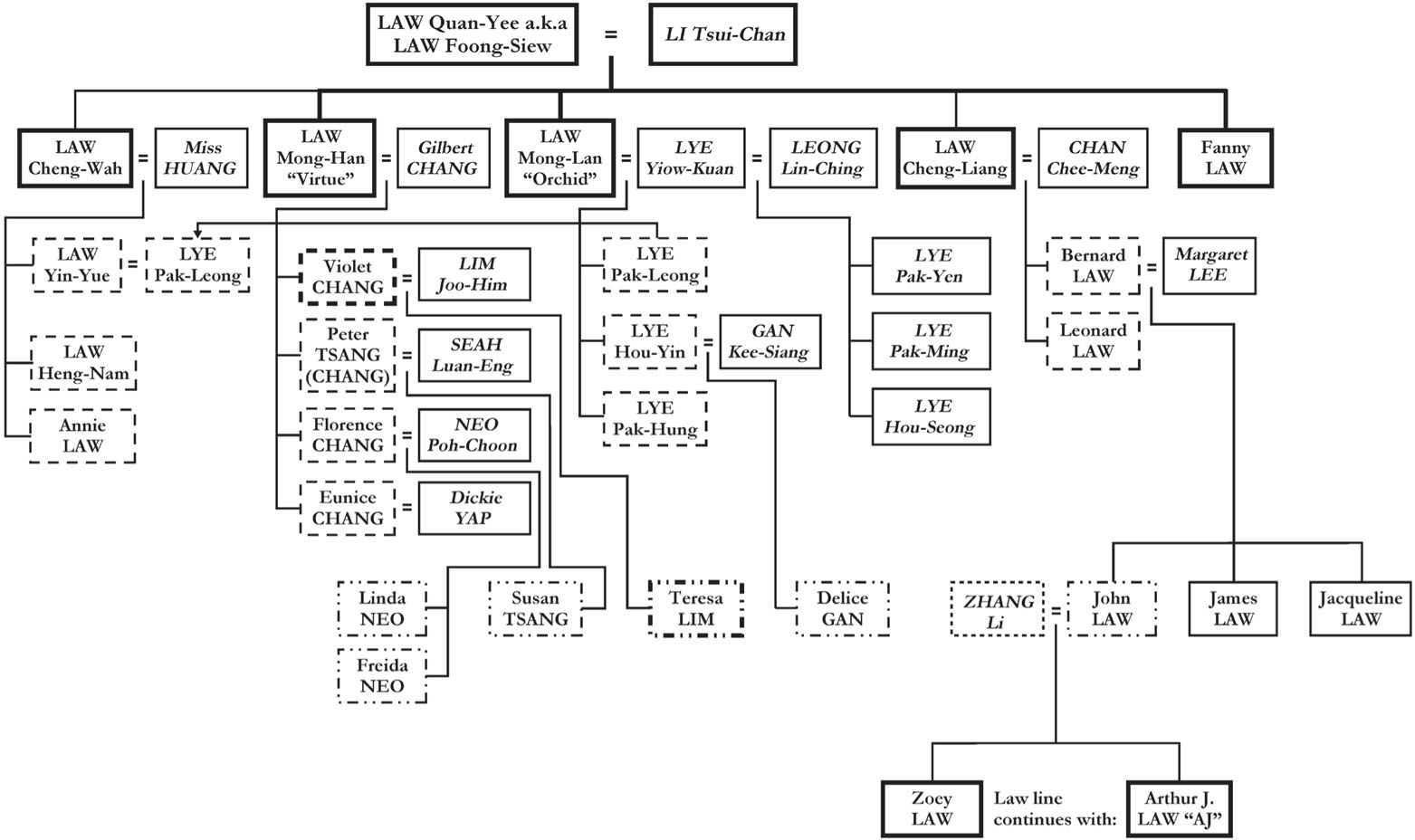

This family tree is simplified to include only the names of those family members mentioned in the book. Peter Tsangs three older sons before Susan are Kenneth, Alan, and Jeffrey; Florence Chang had a third child, her youngest son Soon Teck.

Authors Note

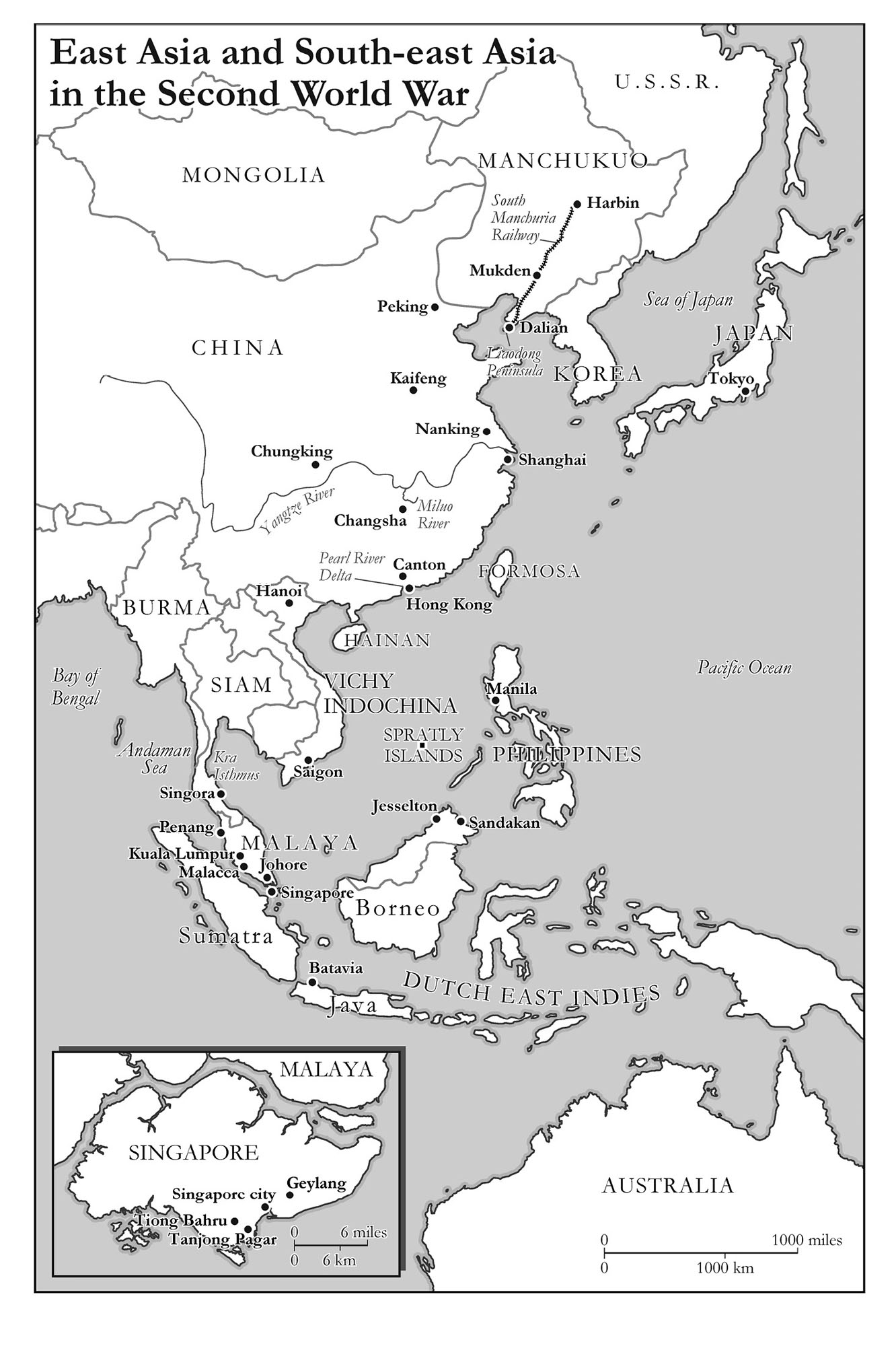

Chinese spellings: Nearly all place names are Romanized according to the WadeGiles system in use during my great-grandfathers time. Exceptions are when there are more familiar forms, e.g. Canton province instead of Kwangtung province or Dalian instead of Ta-lien, or when places are mentioned in a current context. Dynasty names seem less confusing if left in Pinyin. The names of my ancestors in the family genealogy were translated into Pinyin, and I have left them as they are.

Chinese surnames: A reminder that Chinese names traditionally start with the surname first, followed by the given names, usually two. I have hyphenated the given names, e.g. Law Quan-Yee.

Names and terms which were commonly used in the past have been left unchanged for authenticity. I have adopted the same approach when quoting from books written before some of their terminology became offensive to many.

Singapore Chilli Crab

Buy two mud crabs live and quarter.

Pound to a paste a thumb-piece of ginger, two fistfuls of shallot, four cloves of garlic, a pair of red, red chillies.

Heat lard in a wok, add mixture, stir till spicy smells erupt.

Turn up the heat and fry the crabs quickly. Throw in a bowlful of water, a spoonful of sugar, a splash of soy sauce, fiery chilli oil and enough ketchup to make the colours come alive as red and angry as the cooked crab, as fierce as longing or regret.

Thicken with beaten egg. Serve.

Introduction

One cold morning in 1992, on the very last day of February, I arrived to live in Britain for the first time with my husband, who is English, and our three-year-old son. London was as grey and damp as everyone said it would be.

We had left a country full of smiling people, where the air was warm and where our Malaysian housekeeper had knitted a farewell jumper for our son in a colour as bright and optimistic as the sky above our heads: a pure cerulean. It was out of place in London where navy ruled the playground and where, if you were lucky, the early spring sky was dull white with cloud.

We moved into a north-facing house in south London that had recently been burgled of most of its furniture and where the boiler had stopped working. I was in my late thirties, no longer culturally nimble. Everything was surprising or seemed difficult.

I thought that I spoke and understood English my education in Singapore had been entirely in English but it wasnt English in its rich diversity of regional accents and colloquialisms. I couldnt understand the Mancunian telephonist at British Gas or the plumbers who came to fix the boiler. It took a while to recognize Aw-rite? as a greeting.

The nursery-school friend and his mother who came to lunch (We love Chinese food) found my fried rice, with its lashings of treacly oyster sauce, impossible to eat. When I dropped off our son at his classmates birthday party, the children whispered audibly to each other: Thats Victors mother. Shes Chinese.

This was our home now and I wanted to belong. Determined at least to appear more western culturally, I forced every protesting sinew in my body to do as it was bid the first time that I found myself in a swimming-pool changing room with our son. Not looking at anyone, trying to appear as nonchalant as possible, I stripped off completely in front of the other mothers and children while I swapped a wet swimsuit for knickers and bra, T-shirt and jeans. I had heard that this was what European women did. Oops, wrong European country. The entire changing room fell silent.

You dont get to understand a country straight away even when youre fluent in the language.

At the parties that we went to in London they could have been speaking Swahili for all I knew: recently arrived, my mind drew a huge blank around Westminster gossip, the latest English comedians, the latest English bands, the latest English television. There was very little interest in Southeast Asia. As if the region could be any less pertinent, at a dinner in Dulwich a young English solicitor one along on the table placement was surprised to discover that Singapore was once a British colony. Really? she asked.

The chill and anxiety of those early years were warmed and eased by emails from cousins who had also married men from strange, cool climates. There was Freida in Australia, Linda in Germany and Delice in Sweden, their names, like mine, the vestige of a European empire.

They sent recipes like curls of sultry air straight into my cold study, carrying the memory of colour and heat, replicating the smells and tastes that we longed for, of laksas and gorengs bright orange with warmth and promise.

I decided that this could be a great format for a cookbook. We could call it Four Cousins and it would show how we ate our way out of missing home by adapting our Singaporean dishes to what we could buy from the Isemarkt of Hamburg, the marknad of Stockholm, and the farmers markets and supermarkets of Fremantle and south London. But my cousins were less than enthusiastic. Thirty recipes each? Youre mad!

I wasnt ready to give up. I desperately needed occupation, the comfort of activity beyond the everyday when the everyday was reminding me that I was far from home. Here was a project that could keep me close to everything familiar. Perhaps I could win my cousins over if, first, I wrote a preface on the person whose blood we share? Our cookbook would then be more of an extended family essay. Linda, Freida and I have the same grandmother; her younger sister was Delices grandmother. We are therefore first and second cousins with our maternal great-grandfather in common.

We knew almost nothing about him, only that he had left China for Singapore when he was seventeen and had loved his daughters as much as his sons, a remarkable quirk for a Chinese man of his era. It would be worth finding out more but his children were no longer alive and his grandchildren, my uncles and my aunts, had not much more than the odd recollection.

My mother remembered the most. She was the oldest of the grandchildren who had lived with him and I knew her stories. I had asked for them again and again as I was growing up, an only child left at home with the cook all day; to me, my mothers childhood seemed entrancing, crowded with the company of younger siblings and cousins, full of games and pranks.

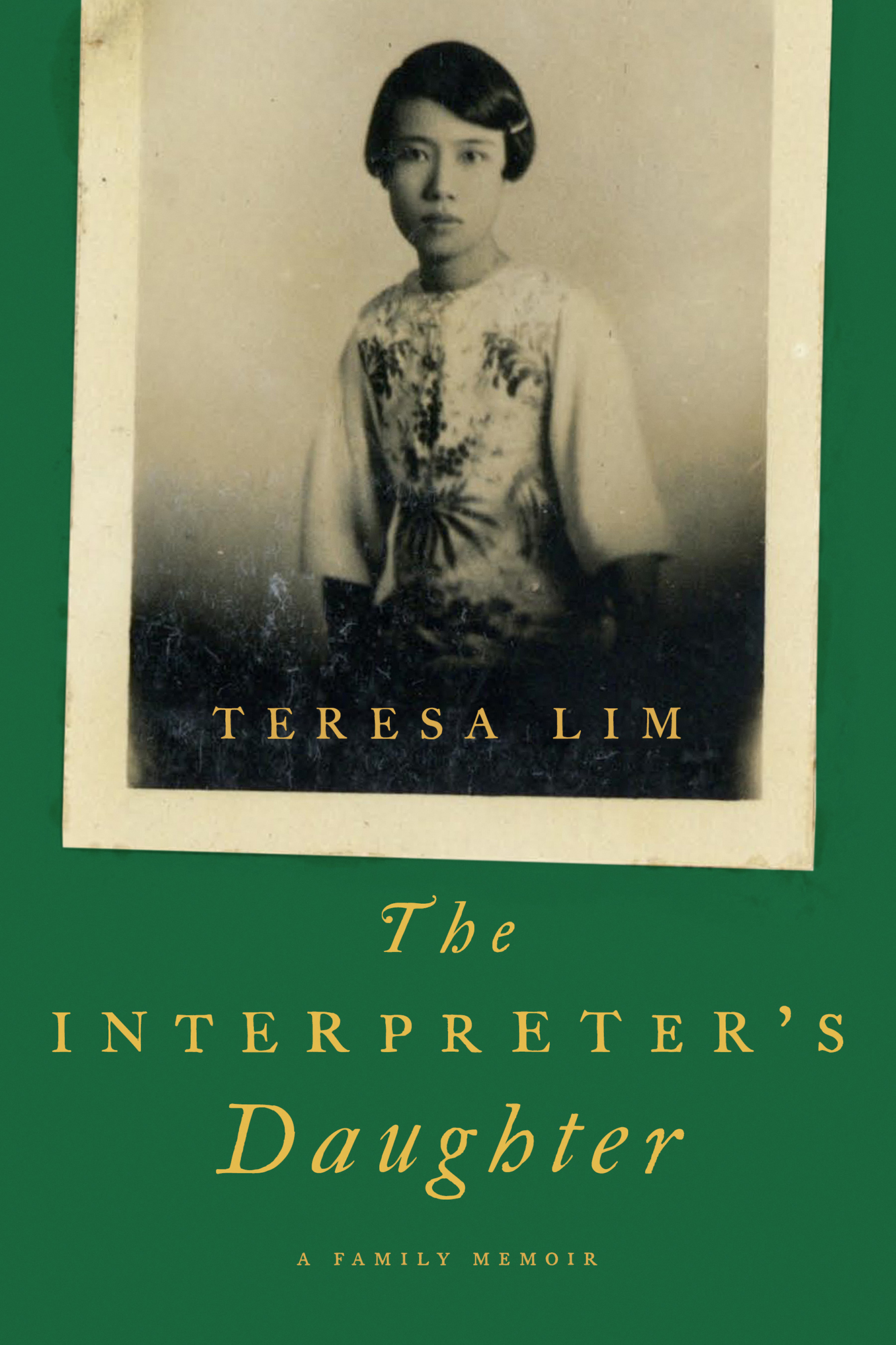

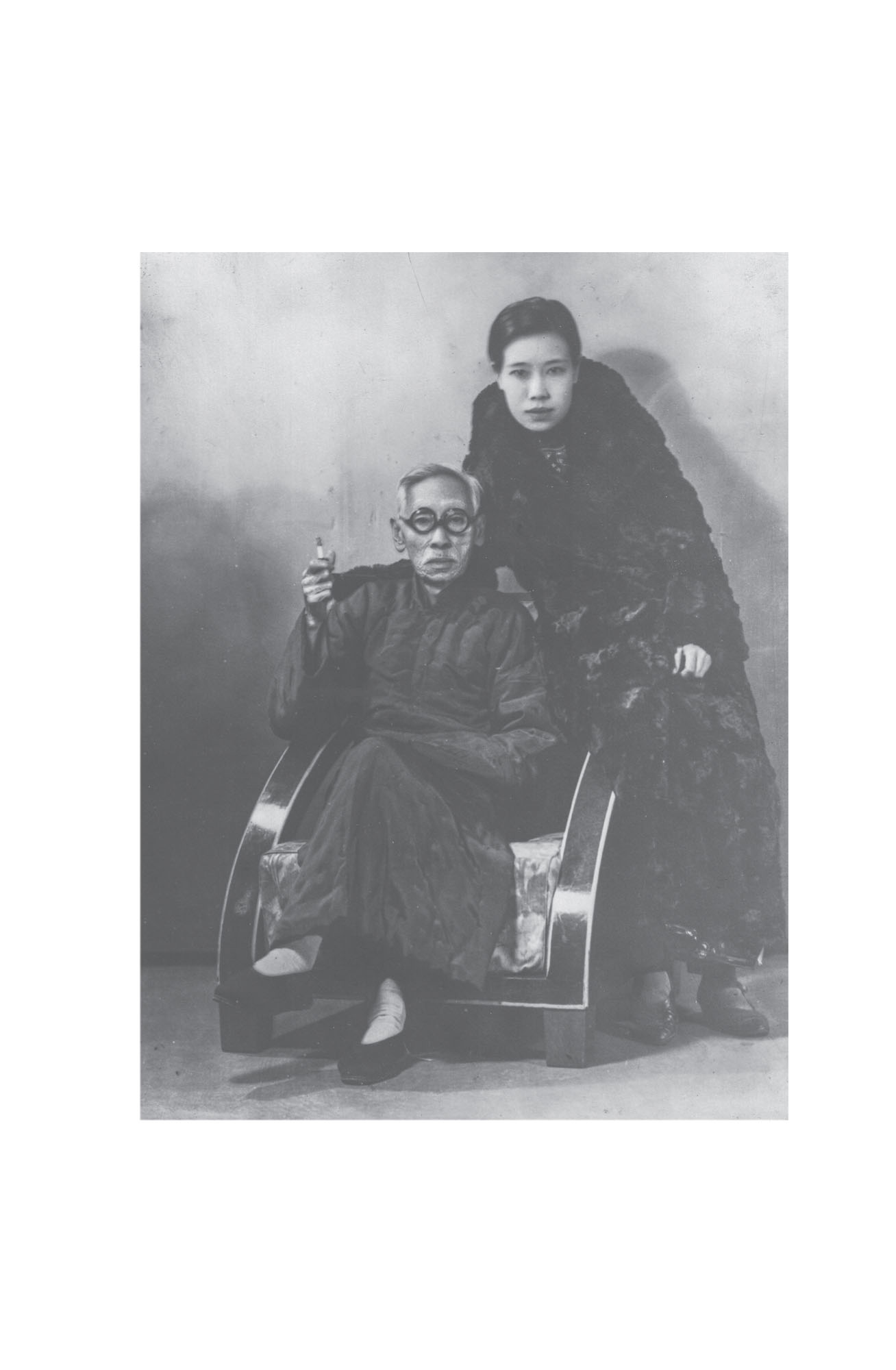

They were only anecdotes, but my mother also had a photograph. I did not know it at the time, but this one clue would take me, over several years, to libraries and archives in Britain and Asia and allow me to follow our great-grandfathers voyage from Canton to Singapore while I reflected on my own transfer to another exotic place, London.