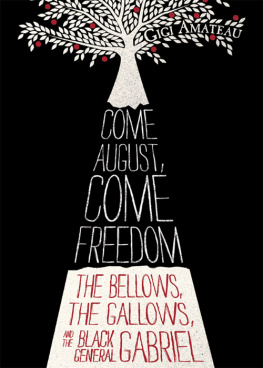

MA BELIEVED . One Sunday before sunrise, she headed out early for church at Youngs spring with her infant, Gabriel, swaddled and slung across her chest. She walked briskly along the footpath that she and so many others before had worn to the creek. Later, Pa would join them for worship, bringing the oldest boy, Martin, while toting the middle one, Solomon.

Since Gabriels birth, Ma kept most of her days at the great house; away from the field, which she was glad to be, but away from her husband, which left her empty. The cook, Kissey, often reminded her to give thanks for Mrs. Prosser, who granted Ma a weekly Sunday reunion, but Ma yearned for more than half a borrowed morning with her family.

Ma did give thanks for her friends. Praise the Lord for Kissey and Old Major, Ma said aloud now as she set her baby down.

In her pocket nestled the apple seeds; she had kept them safe and deep in her apron until the captive ground of winter gave way to springs rightful thaw. The morning smelled of sunshine, new grass, and flowers to come. Before she reached the stream where all the people from all the quarters would gather to pray, Ma squatted down on the still side of the hill. There at the south end of Brookfield plantation, she tugged, and the reluctant earth opened enough for her to place the seeds.

She could hear the tinkle of the creek beyond the field. When the rain comes, before long, that trickle will be a roar, she thought.

Gabriel began to root around for his second meal of the day, and Ma could not help but think of the other hungry babe. Brookfields infant master, little Thomas Henry Prosser, would need to eat soon, too. The missus could produce no milk of her own, so Ma fed both boys.

For times when Ma would be away from the great house, Old Major had fashioned a wooden spout from persimmon wood so that Kissey could feed Thomas Henry the early milk Ma squeezed from herself. If that milk ran out and the little master turned fussy, Kissey would placate him with a sugar teat until Ma returned. The missus rarely asked for her son before noon on Sundays, anyway.

Praise the Lord for Ann Prossers Sunday sick headaches. Ma gave thanks for this, too. She stretched out long in the grass and nursed her six-month-old son without interruption. After while, Gabriel opened his walnut eyes, and Ma gave him her other breast. On some Sundays, he got his fair share.

Ma stroked Gabriels troubled brow. Eat all you like, child. Take whats yours.

When he finished, Gabriel protested being wrapped up so tight. He pushed away from Ma with his head, the only part of him unhemmed and unbound. Kissey had warned her not to loosen his dressing; the crude March air might do the child harm.

Ma unswaddled her son. Another babyd fall fast asleep from such a full little belly. You wide awake, my Gabriel.

She swept him up and then swung him down from the earth to the dawning sky and back. When his tender bare feet brushed along the downy grass, the baby laughed. He tried to stand on his own, and Ma approved. Oh-ho! Where you off to, my strappin boy? You got business at the market, work in the city? My baby boy off to the sea?

What Ma believed was this: her youngest son would grow strong and grow free. He would run pick an apple anytime he pleased, even if only to taste the good fruit given by the Lord, and see, from this spot, the amber sunrise painted by His hand.

She reflected on the talk so often heard in the quarter and the stories Pa brought back from the city, stories of a people insisting on freedom. Tall tales, she had first thought. Tall tales of a David thinkin to slay a giant. Yet Pa had been right all along. Virginia and the other colonies had condemned rule by tyranny and were now at war with England.

Ma prayed aloud for the apple seeds and for Gabriel, her youngest-born. Lord, set my Gabriel free, too. One way or another, set my angel-boy free. She kissed the baby in the hollow of his tender neck and refused to bind him up again.

The Lord sent a gentle rain that same afternoon and a blessed sunshine the next morning. From the soil once full enough to grow tobacco, now completely spent, God and Ma together helped the apple trees roots grow deep and its limbs slowly full on the protected shelf in the hill overlooking the spring. Gabriel grew, too.

GABRIEL LIVED with his mother and his two brothers in a small hut at the edge of the woods, just up the hill from the creek, only a short ways from the swamp, and a fair enough distance from the great house. Their homes only window served also as the doorway to one room, where they cooked and ate, where they prayed and slept.

A hole in the ground held an ever-burning fire for cooking, warming, and keeping away bugs. A second hole, knocked in the wall, drew the smoke out. Beside the fire hole stood a table made by Pa, and at the east end of the room, a bed of Pas hand, too. To make it, Pa had felled a black-walnut tree, stripped the bark, smoothed the boards, and turned the posts.

Ma had delivered Gabriel in that bed, with Pa at her side. Even under threat of a well-laid-on lashing, Pa had not left his wife in her time. And when Gabriel entered the world, Pa breathed on the boy first.

Nowdays, Ma slept alone on the mattress pieced from coarse, heavy Negro cloth and piled with corn husks. Martin, Solomon, and Gabriel slept on the floor Gabriel right at the door. So that the breeze would cool his skin, on hot nights he slept atop a wool rug, issued him by Mr. Prosser. In cold weather, Gabriel curled up beneath his rug and tried to keep warm. And by full-moon light, Gabriel could see well enough to memorize words from the book given him by Mrs. Prosser. He liked his sleeping spot; from this place Gabriel could see and hear everything in the night.

Whenever Old Major, who lived just across the yard, got up to grind his weekly corn ration with the hand mill that all the folks shared, Gabriel knew Mas turn would come next. Every time, Old Majors hound dog let Gabriel know when to rouse Ma. Whether Dog counted up the minutes or whether she detected the slightest finishing-up shift in Old Majors weight, Gabriel did not know. But whenever Mas turn came, Dog always gave a half howl, and Gabriel would then wake his ma. Soon after the little yowl, Old Major and Dog would appear in the yard between the huts.

Last summer was when Dog had first come to them, snarling and growling, seeking refuge in the quarter. At first, the year-old pup had acted more like a rattlesnake than a hound. The women and children hid from her; the men tried to beat and subdue her all except Old Major, who said to the insolent beast, Keep still; you all right. Set down here. I know just how you feel. And soon after, Dog let the people in the quarter come to know her.

Old Major would only call her Dog. The quiet mans own given name had been put away ever since Gabriel could remember. Ma said a dash toward freedom was what got the master started on saying Old Major. Ma said Old Majors run happened before Gabriel was born.