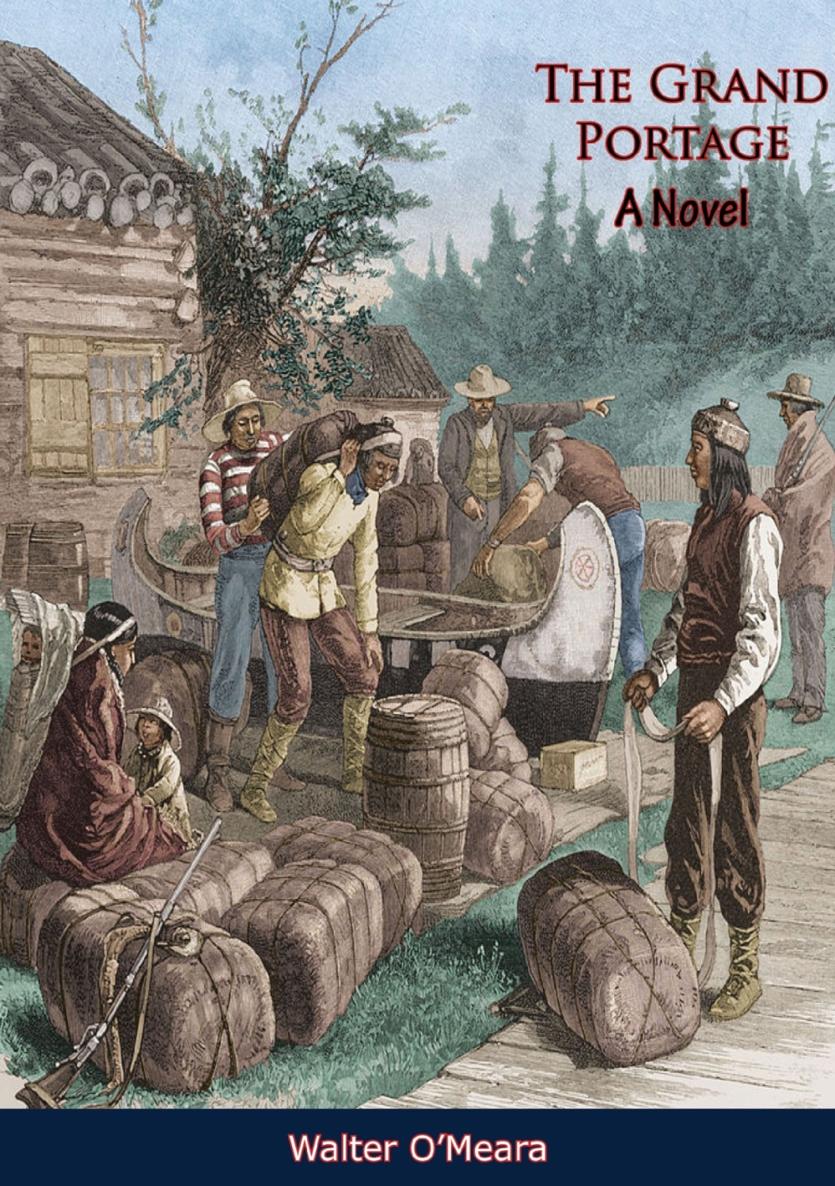

Book One THE RENDEZVOUS

Tuesday, April 29, 1800. La Chine. Yesterday I left Montreal for this place, in company with several other Clerks; and am on my way to the interior, or Indian countries, there to remain, if my life should be spared, for seven years at least. Journal of Daniel Harmon .

1

THE daughters of the Chippewa were not unbeguiling. To the half-wild North Men, fresh from the Up Country, they were of course irresistible. But the canoemen from Montreal were also sensitive to their charms: their pretty black eyes, which they used outrageously on the traders; their quick smiles and flashing teeth; the lazy movement of their bodies beneath their silken doeskins. And even the bourgeois, the haughty overlords of the fur trade, found many of them attractive, some beautiful.

The Chippewa girls at the Grand Portage, Daniel Harmon observed, were more cleanly than their cousins at the Sault; and fairer than the Indians of the southern tribes. They omitted nothing to make themselves alluring, putting fresh vermilion on their cheeks and wearing their smooth hair turned up saucily behind.

Their speech was the soft, gentle tongue of the Chippewa, a language so pleasant to hear and so rich in artful words that it was spoken by all the tribes in council as far south as the Ohio and northward to the Bay. The traders were amused to hear the Chippewa girls pronounce their ls as ns, saying, for example, Michinimackinac instead of Michilimackinac as the Algonquins did.

But Daniel Hannon displayed no interest at all in the particular girl who, with two other Indian women, was approaching him and Duncan McKay along the edge of the Grand Portage bay. He and Duncan, a fellow clerk in the service of the North West Company, had sweated out the day in the hot, stinking storehouse of the fort, marking the fur packs as they tumbled from the presses, ready for shipment to Canada. And now, in the cool of the late June afternoon, having escaped for a little while from the din and confusion of the post, they were loitering along the rim of the bay toward Pointe aux Chapeaux.

It had been a lovely, warm spring day; it was a soft and magical spring evening. Winter had left the Grand Portage late in the year 1800, with rain and snow sweeping across Lake Superior in early June. But suddenly there had come a long succession of bright, hot days that brought the birch and aspen into bud; and already, on the hills beyond the fort, a haze of fresh green clung to the sills and dikes. On this day the south wind, which had blown steadily since morning across Lake Superior, had died down; and the little bay, as round as a ladys hand mirror, lay almost as smooth now in the shelter of the island at its mouth.

A light smoke-haze from the fires of the Indians camp hung over the water, and from the lodges came a murmur like the drone of bees in a budding sugar maple. Beyond this distant sound, if you listened sharply, could be heard the bustle of activity in the canoe yard; and, even more faintly, an occasional shout from within the piquets of the fort. But where Daniel and Duncan had paused to rest there was complete peace. There was no sound save the lazy, leisurely sounds of naturethe slow wash of the surf against the pebbly shore, the call of the chickadees in the alders and the mewing of some gulls on the bay.

The girl and her companionsolder women with the air of duennasstopped at the waters edge to watch a mother gull teaching one of her young to fly. The girl was small and slight, and she walked in the manner peculiar to Chippewa women, toeing in slightly, yet with grace and dignity. About her dress there was a certain elegance that set her apart from the women with her. The main garment of white doeskin was held about her waist by a stiff belt of leather worked with colored quills. The detachable sleeves fell empty from her shoulders, baring her brown, heavily braceleted arms; and a massive silver cross hung by a silver chain about her neck. Even Daniel Harmon, but six weeks up from Montreal, could see that she was the daughter of a chief.

She paused, she and her duennas, to watch the frantic efforts of the fledgling gull, and the young men watched with her. The mother gull was having a most distressing time of it, paddling anxiously about and mewing encouragement, while her ungainly pupil strove vainly to take wing.

I dinna believe the wee bastard will ever get off the water, Duncan McKay said.

And so it appeared as the young gull, trying again and again, each time failed ignominiously. Discouraged, he sat in his ugly fledglings plumage and regarded his parent with a sour eye. The girls laughed gaily at his discomfiture; and she of the silver cross, as if inviting them to share her amusement, turned and glanced toward the young men.

It was an altogether natural and spontaneous act. Any girl in Montreal or Trois Rivires might have laughed toward you in just such a way. And you would have laughed back, no doubt, as Duncan McKay did thenand thought no more about it. Or, even if you were not in the mood for laughter, there would be no need for looking dour; and especially no cause for flushing, as Daniel Hannon flushed when his eyes met that brief, merry glance.

Duncan McKay observed his friend with amusement, curiosity and perhaps a degree of wonder.

Ever since they had left Lachine together late in April, he had been trying to get the measure of his canoe mate; this strange young American who neither cursed, drank, nor joined in the ribald songs of the engags; and who, oddest of all, had no interestor at least admitted nonein the subject of women.