This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

The Haskell Memoirs

JOHN CHEVES HASKELL

Edited by

Gilbert E, Govan and James W. Livingood

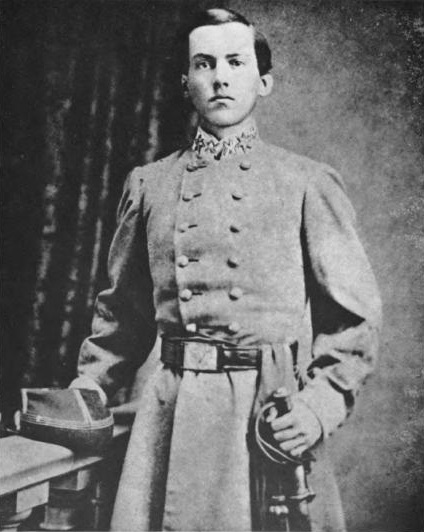

Colonel John Cheves Haskell in His Confederate Uniform.

Authors Preface

I have been so urged by my friends and family to write something of my experiences in the Confederate War that I have, after much hesitation, decided to attempt it and leave its disposition to my family. I have always felt unwilling to publish anything of what I saw during the war because it has been my experience that it is practically impossible for one writing to avoid giving undue prominence to those fragments of the picture in which he took part. Even if he exaggerates nothing and misstates nothing, yet by giving only what he saw or did he apparently excludes acts of more importance and actors who did more.

Having been actively engaged in many of the most active scenes of the war I have never yet seen a record of any part of it which, read by one having no personal knowledge of the facts written of, would fail to give an utterly wrong impression and do grave injustice, by giving seemingly to the writer or to those of whom he writes position and credit to which others were at least partly entitled. It would be without intentional misrepresentation but because the writer saw only one side of the shield and could write only of what he saw. Perhaps it was the silver side, while the gold side got no record, not because the writer would deny it but simply because he did not see it. Nonetheless he will rank in the judgment of those he failed to give credit to as a liar; yet he told only the truth and told all he knew.

I have so often thought that written statements were false and afterwards found they were true, although only part of the truth and so presented as to give almost as false an impression as if wholly false. I have consequently feared that should I undertake to write I might make grave mistakes or tell only some of the facts, leaving out others of more importance; or by telling only those which I knew give them undue weight and thus appear to claim credit to which others are better entitled and of which I do not intend to deprive them.

For these reasons I am, even while writing, full of doubt and hesitation as to the breaking of my long kept resolution. On the other hand, as time passes it becomes more important that the testimony of each witness be recorded for possible use in making up the record. I have decided therefore to write some of what I saw, and leave it to the judgment of my family to decide if it shall be used.

In December 1860 the whole state of South Carolina was in ferment. Many experienced men as well as all the young and inexperienced had gone wild on the subject of secession, and were anxious that Lincoln should be elected. It was believed that his election would sweep the South from the Union over the opposition of those who did not favor secession and were regarded almost as traitors.

I well remember the night when the news came that Lincoln was probably elected. I with a party of other college boys went to Hunts Hotel [in Columbia], where several speeches were made. Among the speakers was F. J. Moses, a prominent lawyer from Sumter, who in a most violent secession speech hoped the report of the election was true, as it would sweep away the opposition of the weak-kneed and hesitating, like his valued and timid friend, Wade Hampton. Moses lived to be a prominent member of the infamous carpetbag government that wrecked the State from 1868 to 1876. He was Chief Justice of the Court of Appeals, while his son, F. J., Jr., was for years the leader in all the worst thievery and corruption, winding up as Governor.

Neither father nor son ever went into the army. His timid friend, Wade Hampton, entered the war and his history is a large part of that in the next four years. His next appearance was when the State called him in 76, when the carpetbaggers and their allies were turned out, the Moses, father and son, being among those deposed at that time. Justice Moses rendered honest decisions, which were of great benefit, and was generally believed to be in sympathy with the decent people of the State. His son was to the last allied with the lowest element of the plunderers, and led a vigorous fight in their own party against D. H. Chamberlain, who refused to sign the commission of the younger Moses as judge, a position which he sought only for the opportunities it would give him to sell decisions.

Chamberlain, who was governor from 1874 through 1876, took the ground boldly that the younger Moses and W. J. Whipper, both of whom had been elected judge, were unfit and that he would not give his assent to their being put on the bench to disgrace it. Chamberlains course was one of the first steps toward a better state of things, and it was a heavy blow at the Reconstruction party, whose only bond was plunder. It made a most effective break in their party, which cared nothing for success except as it meant free plunder. They considered Chamberlains efforts to make their party honest and decent a blow at the only liberty they valued, License.

Chamberlain was one of the few men of character and education who came South after the war. Even they believed that Northern thrift and economy would reap rich harvests from the development of the Souths great natural resources. They did not realize the insuperable difficulties of working with labor which for generations had been but irresponsible chattels, whose one idea of freedom was license, whose foresight never looked beyond the needs of the day, and who could not realize that with the power to govern themselves had come the burden of supporting themselves, the helpless children, and old people, who had been cared for as well as controlled.

Some of the Northerners thought they could direct the ignorant, grateful negro, even making rich profits while elevating the former slave. But they either gave up in despair, losing all they had put in, or went with the crowd and made profit of their intelligence in a division of plunder. Those who failed in an effort to make an honest government are still entitled to much credit. They did much to counteract the great wrong they did the South by attempting to control its destiny and giving a kind of moral support to what would, if left to itself, have perished of its own corruption in a tithe of the time that it stood, a blighting pestilence over the whole South.

![Will Kurt [Will Kurt] - Get Programming with Haskell](/uploads/posts/book/116897/thumbs/will-kurt-will-kurt-get-programming-with-haskell.jpg)