Translators Preface

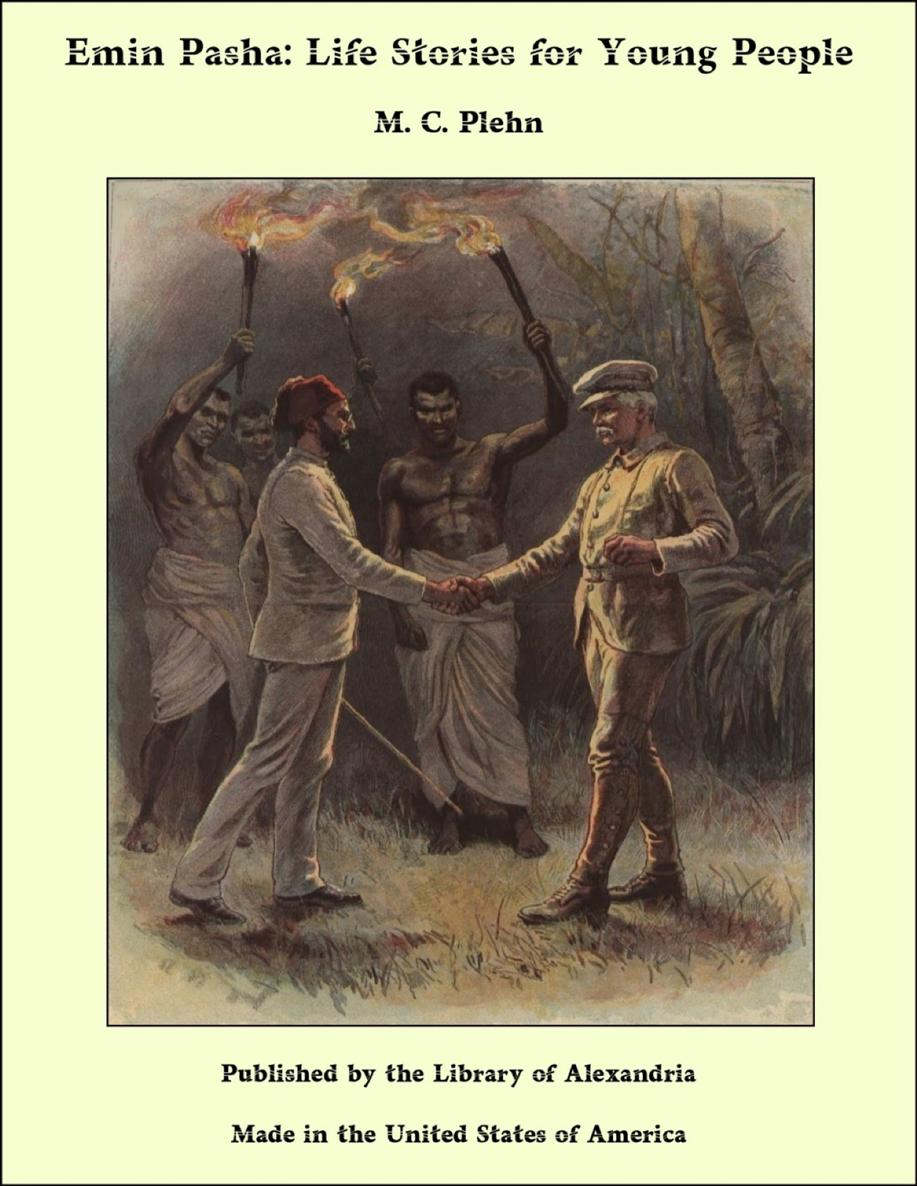

Emin Pasha, sometimes called the father of the Equatorial Provinces, is a notable figure in the records of African exploration. He was preminently a scientist and was devotedly fond of zology and botany. Amid all his cares of office, his sufferings from the hardships of African exploration, his neglect and ill-treatment at the hands of the Khedive and his ill-health and growing blindness, he pursued his scientific investigations with passionate ardor.

No African explorer ever had the welfare of the Soudanese more at heart than he, and yet he met a cruel fate at the hands of treacherous Arabs and was murdered while studying his favorite plants and birds. In all his long career he never injured anyone, but constantly strove for the welfare of the natives and retained his confidence in them after it was apparent to almost everyone else that they were treacherously conspiring against him.

The German author now and then hints at friction between Emin Pasha and Stanley, and is inclined to blame Stanley for indifference as to Emins fate after he had been sent to bring him relief. The friction, if it existed, was probably due to the different temperaments of the two men. Emin Pasha was conservative, blindly attached to the Soudanese, certain he could govern them by mild measures, a quiet, reserved scholar passionately devoted to scientific pursuits and at home in Africa, rather than an explorer. Stanley was a man of action, bold, and dashing, who, in the phrase of the day, might be called a hustler. It is undoubtedly true that at times he had little patience with Emins slowness and cautiousness and his scientific absorption which sometimes rendered him oblivious to dangers besetting him.

G. P. U.

Chicago , July, 1912

Chapter I

The Father of his People

As the famous traveller, Dr. Junker, on the Nile, on the twenty-first of January, 1884, after a years stay in the Soudan, he felt that all his privations and dangers were at an end, though many hundreds of miles still separated him from his home. After having been deprived so long of nearly everything that we consider the ordinary necessities of life, after wandering alone in the wilderness, in primeval forests and over sunburned plains, among cannibals and cruel man-trafficking Arabs, he knew that he would find a white man in Lado who could speak his native tongue,a zealous scholar and finely cultured man, who would acquaint him with everything from which he had been excluded so longa friend who would welcome him with a cordial grasp of the hand; in a word, Emin Pasha, that heroic governor of the Equatorial Provinces, whose strange fate and cruel murder filled the whole civilized world with astonishment and sympathy.

After a short days march through the country of the Bari, the traveller was certain that the end of his journey was not far distant. How different were the well-cultivated farmlands from the wilderness, interspersed here and there with Arab settlements. The negroes had their property well protected, their herds were grazing in all directions, and the people of the numerous villages did not flee, but kept calmly about their work. Dr. Junkers servants were astonished when they saw that in this country the stronger did not appropriate the property of the weaker and that the Turkish government had not disturbed them.

As the expedition neared the station, shots were fired as a welcome. The advancing boys and carriers made way and Junker perceived a body of men in faultlessly white garments coming to meet him. At their head he at once recognized his friend, Dr. Emin Pasha, a slim, almost haggard man of little more than medium height, with a small face, dark full beard, and deep-set eyes, whose sight was rendered keener by spectacles. His demeanor and movements impressed one with his composure and self-control. His external appearance betrayed an almost painful neatness. He and his attendants rode mules and six black soldiers in white uniforms followed him. To Dr. Junker it appeared a festal procession and tears came to his eyes. He sprang from his horse and greeted his friend first, then the others. The rest of the distance to the station was made on foot, the two eagerly conversing.

What a change there had been at Lado since Dr. Junker last saw its miserable rush huts, six years before. At that time, Emin had just begun his difficult administration. The changes which they saw all about them testified eloquently to the governors abilities.

The man holding this high position in the Soudan arose from humble circumstances. His real name was Edward Schnitzer. He was born at Oppeln in Silesia, in 1840, and shortly after his family removed to Neisse, where many of his relatives are living to-day. We know little about his youth, but we are told that the boy was an enthusiastic naturalist, fond of making collections of flowers and insects, and even at that time noted for his reserve and thoughtfulness. Both these characteristics are observable in the man. The study of nature was his principal recreation and compensated for his lack of human intercourse. But his conscientious devotion to science and his aversion to publicity leave us little knowledge of his accomplishments or his real sentiments. Even his most intimate friends knew little of his inner nature, and while his letters to European scholars reveal his varied activities, yet they are of no value in throwing light upon his nature, which makes it difficult to understand some of the actions of the man.

Edward Schnitzer studied medicine in Breslau and Berlin in 1863-64 and took the doctors degree. It was his love of nature that led him to go abroad. He went to Trieste and Antivari, and from there, with a Turkish companion, Hakki Pasha, to Trebizond. He soon succeeded in gaining respect and influence. His facility in adapting himself to the habits of the places where he was stopping, the remarkable ease with which he learned languages (he spoke Turkish and Arabic as if they were his native tongues), and the success which attended his medical practice, quickly brought him fame and importance; and when, as was the custom in those countries, he changed his German name to a foreign one (Emin, the Faithful), he was hardly recognizable as a European. In the company of Hakki he explored Arabia and then went to Janina and Constantinople. When his protector died, the young physician returned home and devoted himself entirely to scientific pursuits. But soon the monotony of everyday life and its quiet regularity, the colorless northern landscape, and frequent cloudy skies became unendurable, and he suddenly decided to make a change. In 1876 he went south again, this time to Egypt. He reached there at just the right time, for the enterprising Khedive, Ismail Pasha, was attracting large numbers of Europeans to his country because of his extension of the limits of the ancient kingdom of Pharaoh far to the south and the west.