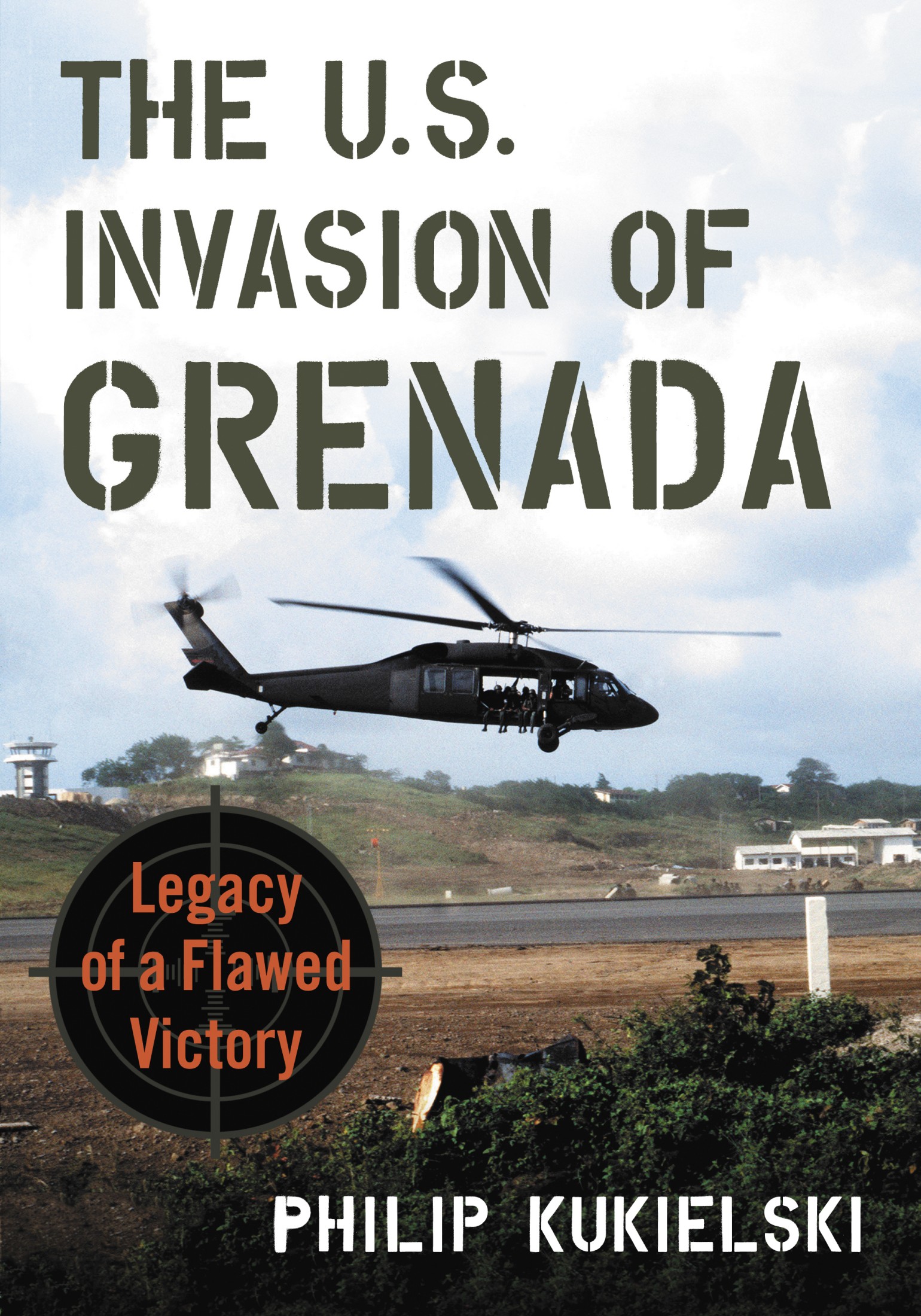

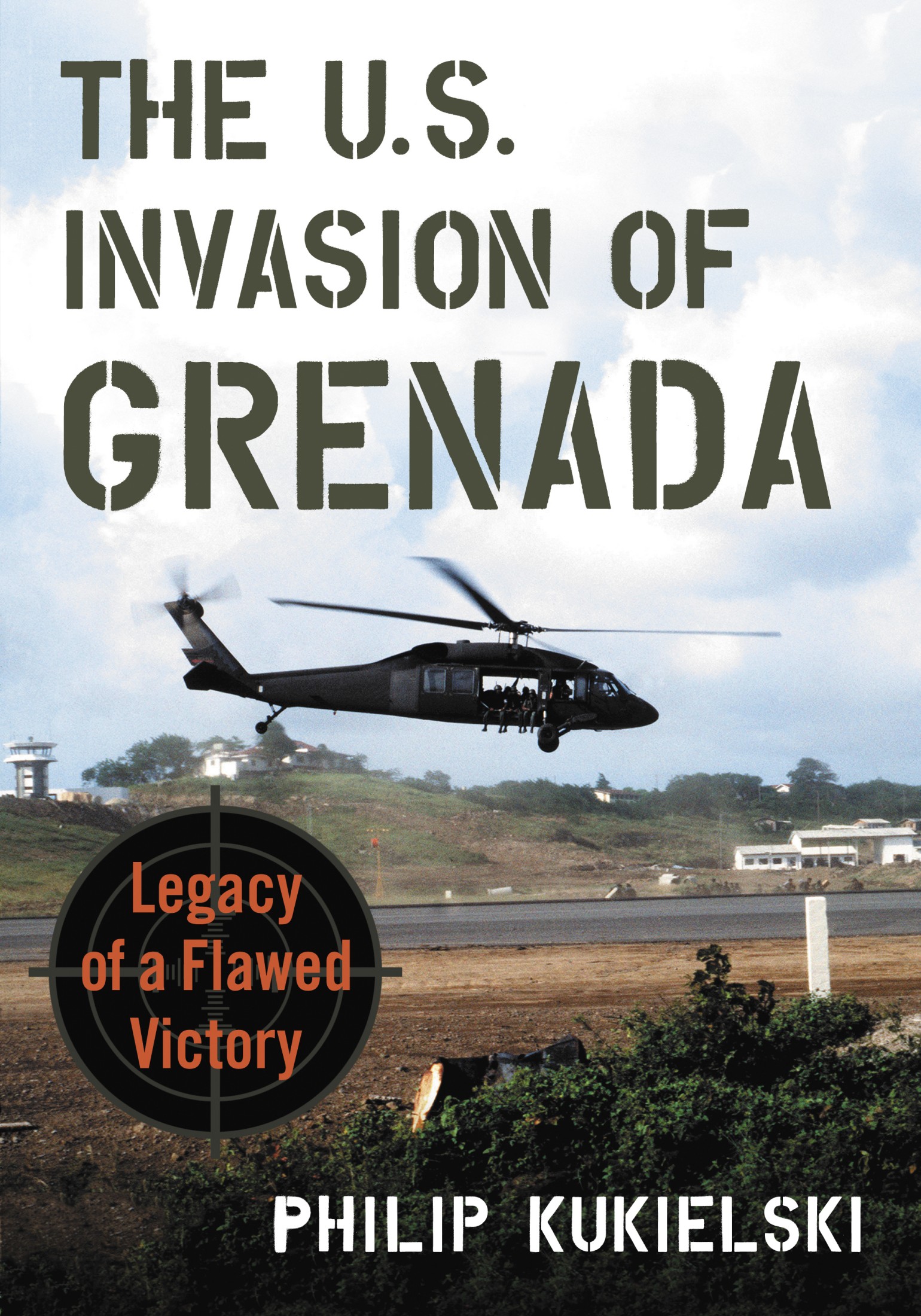

The U.S. Invasion of Grenada

Legacy of a Flawed Victory

PHILIP KUKIELSKI

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3832-

2019 Philip Kukielski. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: A U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter in Grenada during Operation Urgent Fury on October 25, 1983 (Department of Defense)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Elisa, editor-in-chief

of my life and work

Preface

The secret invasion of Grenada in the fall of 1983 took me, and most Americans, totally by surprise. Like most of my countrymen, on that day, I could not have successfully pointed to the island on a world map. Nonetheless, I had chosen a profession that routinely required me to write about subjects starting from scratch. On the morning of Oct. 25, I was a local news reporter assigned to the city desk of the Providence Journal in Rhode Island. My boss sought a local angle on the invasion to supplement the sparse wire service reports on the invasion then emanating from Washington and the Caribbean. I was dispatched to the suburban home of a ham radio hobbyist, who was monitoring shortwave broadcasts from the embattled island.

My D-Day vantage proved better than mosteven though it was 2,141 miles away from the fighting. I spent the afternoon and early evening listening to tension-filled shortwave broadcasts from American civilians on Grenada. I was surprised to discover that the squawky reports I heard on the public airwaves were also being closely monitored at the top levels in Washington. These real-time, eyewitness accounts turned out to be the most reliable information that anyone stateside was getting that day about what was happening to U.S. civilians on the island. The principal conversation I overheard was between an American medical school student on the island, who had a generator-powered ham radio in his dorm room, and an American hobbyist, who had a rig at his New Jersey home. The student ham reported on the movements of Grenadian soldiers, who had surrounded his beachfront campus, and the U.S. soldiers and airmen, who had been sent to evacuate him and his American classmates at St. Georges University Medical School. The students stateside interlocutor asked questions that came from the State Department. At one point, I heard another ham interrupt the conversation to say he had a White House military attach on the line. This ad hoc, radio-relay link struck me as a most curious way to manage a supposedly secret, multi-national rescue mission.

This mystifying D-Day experience was the start of a long personal quest. The story that follows here is the product of a decades-long journalistic inquiry into why, and how, the worlds greatest superpower waged an impromptu, one-week war with a Caribbean microstateand to what enduring effect. My initial zeal for this subject was fueled by soon-to-follow sad news. One of the 19 Americans killed during the invasion was Lt. Jeffrey Scharver, a Marine helicopter pilot from Barrington, Rhode Island. His Cobra attack helicopter was shot down when he was providing covering fire for the rescue of another downed Marine pilot. I was assigned to write an in-depth story on the circumstance of his death for the statewide papers Sunday magazine. As I interviewed the Marines who served with Scharver, it became apparent that his final flight was a risky and unexpected mission. His two-man Cobra was called upon to perform heroic actions in order to set right a cascade of events that had gone wrong for Navy SEALs in the first hours of the fighting.

Extracting the full story of Operation Urgent Fury from the web of secrecy that encased it did not prove to be an easy journalistic assignment. Reporters were barred from the battlefield for the first three days of the operation. By the time they were allowed to set foot on the island, the fighting was essentially over. The after-action reporting by journalists never quite caught up with all that happened prior to the press corps arrival. By the end of 1983, order had been restored on Grenada. American combat troops and foreign reporters came home. The southernmost Windward Island, a nation the size of Atlanta, again faded into insignificance on the world stage.

But the military flaws of Urgent Fury were like the fabled peas under the mattress for the Pentagon. The American Goliath did not rest easy on this preordained victory. As time went on, details of the operations many snafus leaked out in various public forums. The Grenada experience got inexorably drawn into a then-simmering Washington debate over Pentagon organizational reform. In 1988, I wrote a fifth anniversary piece on the invasions unexpected afterlife as a catalyst for change. I interviewed many of the key military players in the invasion, including the late Vice Adm. Joseph P. Metcalf III, the on-scene invasion commander, who had recently retired. My understanding of the operation was further advanced by two working vacations I subsequently spent in Grenada in the next few years. I toured battlegrounds and wrote about the islands nascent efforts to convert to a tourist-driven, free enterprise economy.

For many years, even decades, the best independent, unclassified history of the invasion was Mark Adkins Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada, published in 1989. In 1983 Adkin was a British infantry officer serving on the staff of the Barbados Defence Force, a principal contributor to the multinational invasion coalition. Adkin had first-hand knowledge of the role played by all the Caribbean parties, including the Cubans and Grenadians. But Adkin was not privy to portions of the invasion story that played out in Washington and on military bases in the continental United States. Details from these sources, and others, dribbled out after 1989 in subsequently declassified military monographs, scholarly books, academic journals, military studies and memoir accounts.

This updated narrative of the invasion and its aftermath was assembled from shards of public information scattered across more than three decades. Putting the story together into a coherent chronological account has been akin to assembling a mosaic from thousands of pieces of irregularly shaped and variably colored glass. The central problem with telling the full story of the invasion, even now, is that virtually all the U.S. governmentcreated information about the operation was initially classified top secret or higher. That classification stuck like a birthmark to the source material long after there was any compelling national security reason for keeping most of the information secret.

As a practical matter, I found that the principal way that initially classified information regarding Urgent Fury subsequently became public was if someone in authority who was privy to the information saw a particular benefit in having select material reviewed for release. This was typically done so that a particular document could be broadly shared with a larger audience to serve a training, policy or public relations purpose. Other formerly classified information was revealed in memoir accounts written by, or for, former Reagan administration policymakers or special operations veterans. This insider-driven declassification system was supposed to have changed under an executive order issued in 2009 by President Obama. That revision of the classification system was aimed at expediting targeted declassification requests filed by the general public, principally historians and journalists. The 2009 order also raised the bar that agencies had to meet to still keep historical information classified after 25 years. That quarter-century benchmark was passed in 2008 by Urgent Fury. Regrettably, in my research, I found scant evidence of substantive declassification of Urgent Fury historical records on the 25-year mark by the military on its own initiative.

Next page