FIDEL AND CHE

A REVOLUTIONARY FRIENDSHIP

SIMON REID-HENRY

CONTENTS

I had a brother.

We never saw each other,

but it didnt matter.

I had a brother

who passed through the hills

while I slept.

I loved him in my fashion

I took his voice

free like water,

I sometimes walked

close to his shadow.

We never saw each other

but it didnt matter,

my brother awake

whilst I slept.

My brother showing me

from beyond the night

his chosen star.

JULIO CORTZAR, I HAD A BROTHER

Abu Isaf is more than a brother to me, as you know. Being comrades in arms is something that time cant erase; after you havent seen him for twenty years, your comrade in arms turns up and you discover he still has his place in your heart.

ELIAS KHOURY, GATE OF THE SUN

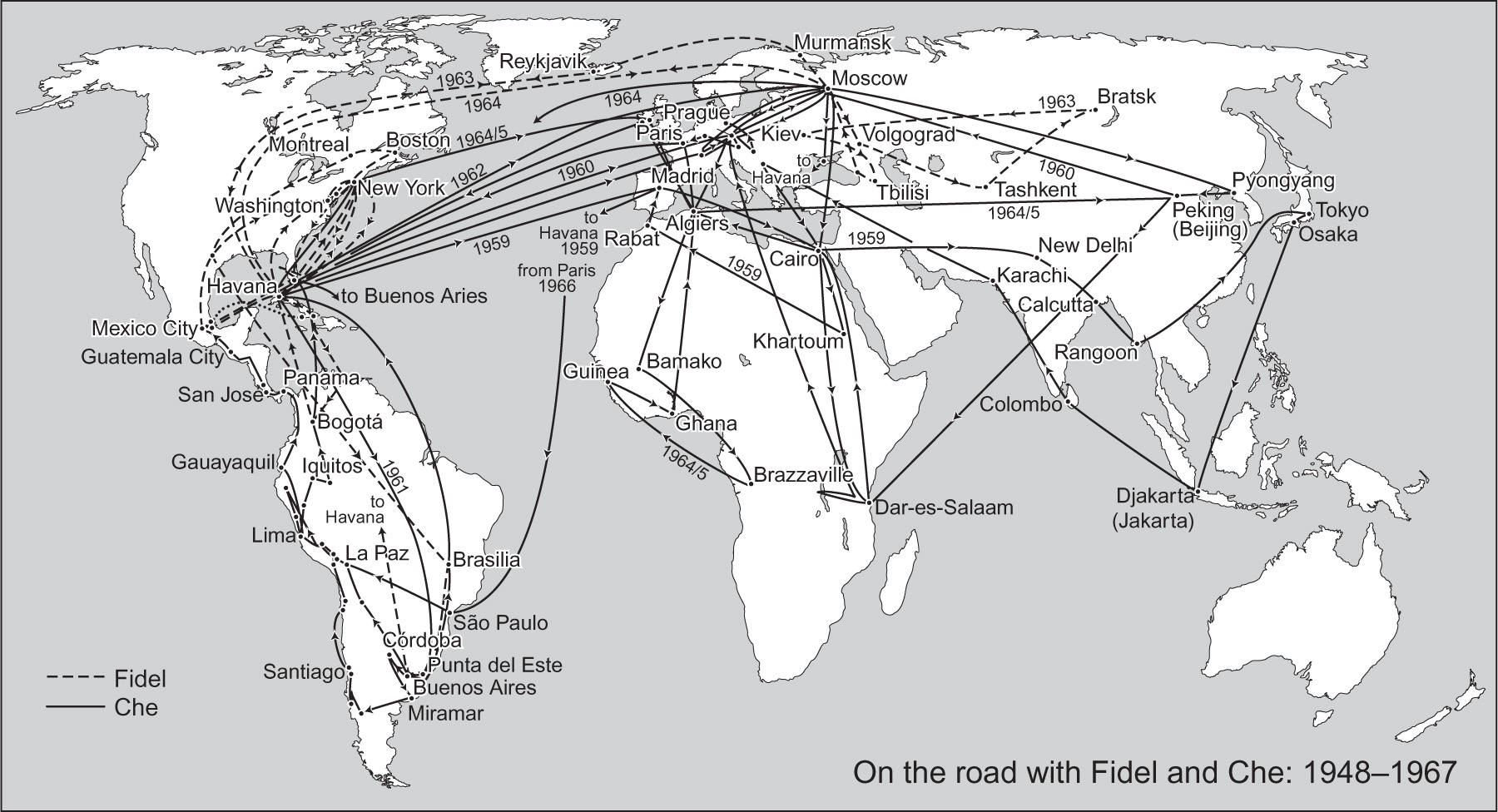

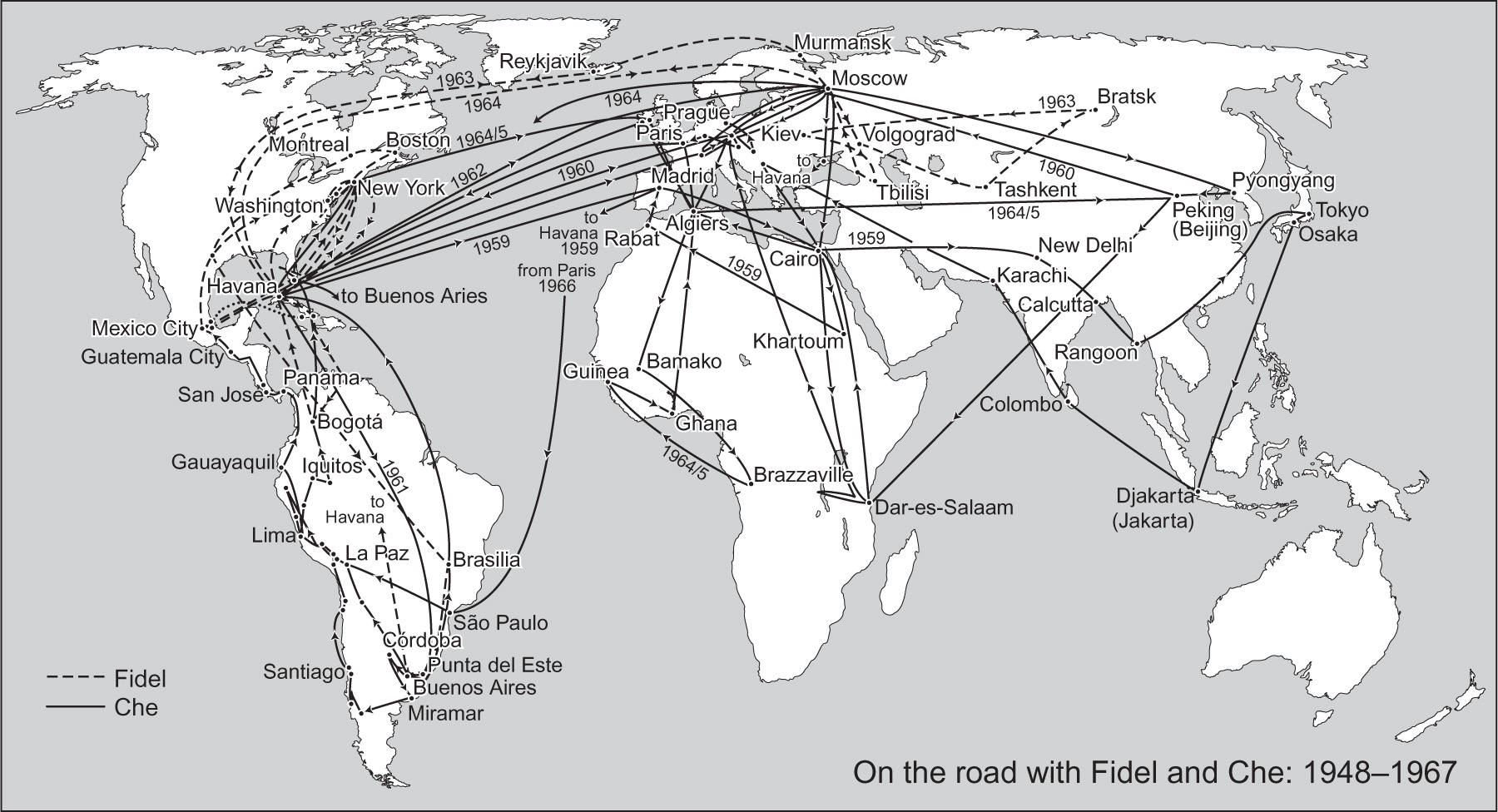

Fidel Castro is addicted to the word, as his good friend Gabriel Garca Mrquez puts it. This makes it all the more surprising that during his half century in powerby far the longest effective rule of any recent head of statehe has said so little about his twelve-year friendship with Ernesto Che Guevara. Yet theirs was a friendship that spanned the beginnings of the Cuban revolution and the high point of the cold war, a friendship that for a time was arguably the most important relationship in both mens lives, and one whose secrets offer a unique window into one of the defining events of the twentieth century.

In October 2007, on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of Che Guevaras death in Bolivia, in a message to the Cuban people dictated from his bedside, Castro looked back at the sad and luminous days he and Guevara once shared. The phrase was not his, but in a certain way it belonged to him. In 1965, two years before he died, Che had scribbled it down on a sheet of lined paper as, forever in a rush, he penned a last-minute farewell to Fidel, his comrade of the previous ten years. This unusual good-bye did not end their relationship, and the circumstances in which it was written were themselves to play a part in the closing stages of their story. But Castro never publicly replied. Even forty years later, and himself then suffering from the intestinal problem that would see him officially retire from office, the great orator merely noted that Guevaras life had been like a flower cut short in its prime. Of his true thoughts on the matter he offered not a glimpse.

Such reticence about the past is unusual for someone with Fidel Castros avid interest in history. Castro has regularly staked his revolution on the popular appeal of the islands history of rebellion, and he will always be associated with the famous line Condemn me, it does not matter; history will absolve me! But he has also alwaysand with not inconsiderable successdiscouraged serious historical research into his own past. He has been especially protective about his relationship with Che Guevara, limiting his comments to the occasional exclusive (if not always revealing) interview or republication of some of his earlier speeches.

Guevara, too, tended to smudge the details of his own life. His now much-publicized diaries are fascinating insights into the revolutionary process and the growing radicalization of an ordinary boy from a well-to-do background as he journeyed into the more impoverished parts of the South American continent and ultimately well beyond this. But they are all accounts that he rewrote after the events, and, accordingly, they fit with the vision he wanted to convey. They retain much of value and insight, but are not as objective as he perhaps would have liked to think. It is not all that surprising, therefore, that for many years in-depth accounts of the lives of these two most colorful and important characters of the twentieth century were hard to find.

Despite the emergence in the last two decades of a good number of often very detailed biographies on both men, the depth and subtlety of Fidel and Ches relationship in many ways remains a ghostly flicker, like the gray blur Stalin presented to biographers over many decades. Yet their relationship was of paramount importance to both men during those critical years, as important in its own way as the intellectual camaraderie of Engels and Marx, or indeed the great clash of egos that marked the partnership of Trotsky and Lenin. Fidel and Che had at least something in common with these other giants of Communism, and more besides, for they were not just comrades but compaeros who found common cause at a remarkable historical moment when the cold war intersected with the nationalist struggles of their own and other countries. But their relationship differs from these and many other political double acts in that it was a full-blooded friendship first and foremost, and it was lived out during just a few short, intense years. It was, as one biographer put it, quite simply unmatched.

This book is about that unmatched relationship and the coming to prominence together of Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara in Cuba: that small space, where two of the great epics of our time coincide.Moscow, Miami, Princeton, Boston, London and Berlin. Drawing also on interviews with some of the major figures in this history, it brings together a novel range of sources to tell at full length for the first time the story of one of the most intriguing political friendships of the twentieth century.

IN THE EARLY HOURS OF THE MORNING of November 25, 1956, there was unusual activity at the small port town of Tuxpn, one of the few settlements situated between Veracruz and Ciudad Madero on the long, sweeping arc of Mexicos eastern coast. Soaked by a windblown drizzle that foretold an approaching storm, a small group of men were busily carting biscuits, water and medical supplies up a precarious gangplank to a small pleasure craft tied up alongside the river that flowed down into the port. Two attractive young women gave a hand as Hershey bars, oranges and a couple of hams were stowed among the rifles, ammunition and antitank guns already on board.

Overseeing these last-minute preparations was the six-foot-two figure of the Cuban lawyer Fidel Castro, one of that countrys most promising basketball players in a life that could have been; a largely unsuccessful practitioner of law turned politician and now amnestied revolutionary in the life that increasingly was. Everything he had worked for since walking out of Jesuit school in Havanahis gangster days, his enrollment in armed operations, his months of solitude in prison and, more recently, the long nights of clandestine preparations in exileall were staked on the success of the next few hours.

Standing nearby in the darkness was the much leaner figure of the Argentine doctor Ernesto Guevara, until then a somewhat reluctant medic and scientific researcher who was at heart a wanderer and a poet. He, too, stood that night on the brink of a new period in his life, one from which there would be no return but which he had sought, perhaps without quite knowing it, all his life. The two men did not speak as the silent mobilization got under way.