www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2017 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2017

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Goss, Nina. | Hoffman, Eric R.

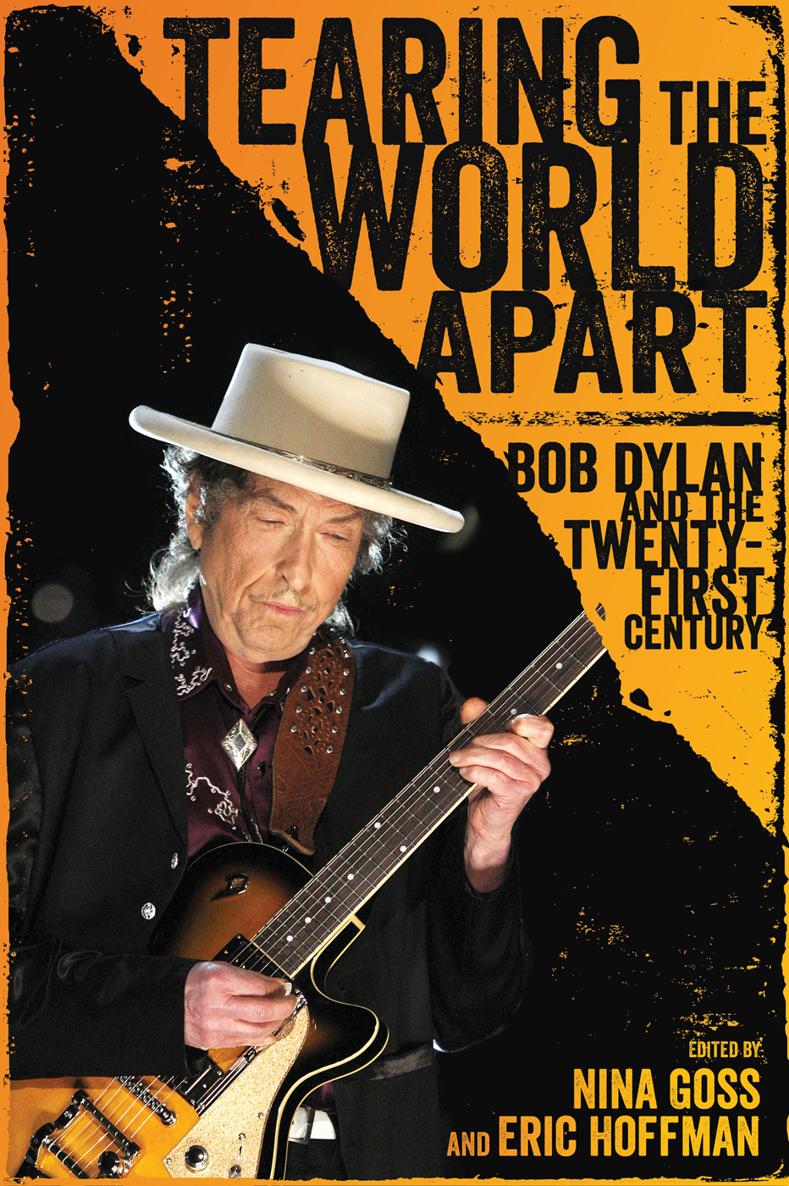

Title: Tearing the world apart : Bob Dylan and the twenty-first century / edited by Nina Goss and Eric Hoffman.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2017] | Series: American made music series | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017011365 (print) | LCCN 2017013224 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496813336 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496813343 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496813350 ( pdf single) | ISBN 9781496813367 (pdf institutional) | ISBN 9781496813329 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Dylan, Bob, 1941Criticism and interpretation. | Popular musicHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML420.D98 (ebook) | LCC ML420.D98 T43 2017 (print) | DDC 782.42164092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017011365

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

INTRODUCTION

On November 18, 2015, five days after the Paris bombings, Bob Dylan performed in Madrid; armed guards were posted at the venue. News accounts reported that Dylan had insisted on this increased security; Dylan offered a public statement explaining that he had not personally requested armed protection. Also in November, Sony released several iterations of a treasure chest: the heretofore-unreleased tapes of Dylans 196566 recording sessions, the twelfth volume of the voluminous Bootleg Series. This hoard of hoards comprises eighteen compact discs and has been offered in an extravagant limited edition package for a list price of US$599.

Thus, in less than one month, Bob Dylans actions are commented on in the context of todays grievous world, and Bob Dylans fifty-year-old recording detritus is avidly consumed and examined. Go back a couple of months and Bob Dylan is in the running for the Nobel Prize for literature,1 and selling half a minute of charm to IBM for use in a television ad, the latest in an ongoing, perhaps entirely cynical late-career flirtation with the lucrative world of advertising. Musicians selling products became commonplace by the 1980s; even Willie Nelson was doing itthough admittedly he owed money to the IRS (and anyway, comedian Bill Hicks, who otherwise declared that musicians who deigned to whore themselves to commercial advertising were immediately off the artistic roll call, was all too willing to give Willie a pass, given the circumstances). I used to care, Dylan sings in his sole recorded Y2K output, a contribution to the soundtrack for Michael Douglas film Wonder Boys (2000), which concerns an aging Boomer staring down mortality, but things have changed.2

In fact, once a counterculture icon, Bob Dylan has a long and storied history as a corporate shill, licensing his 1964 song The Times They Are a-Changin to an accountancy firm (1994), Canadas Bank of Montreal (1996), and insurance conglomerate Kaiser Permanente (2005). More recently, hes sold the rights to such iconic songs as 1973s Forever Young to Pepsi in a reprehensible 2009 Super Bowl ad that used a horrendous will.i.am rap sampling of Dylans song played over a predictable montage of 1960s Dylan footage. Dylan has also made appearances in commercials, including Cadillac in 2007, selling environmentally unfriendly, Boomer-marketed Escalades no less, and, notoriously, in a 2004 Victorias Secret commercial that made use of Dylans song of romantic defeat, Love Sick from Time Out of Mind (1997), made all the more interesting due to a comment Dylan made nearly forty years earlier during a widely seen, lengthy 1965 television conferencefilmed during the height of Dylans countercultural relevancewhere Dylan jokingly told one interviewer that someday he would like to sell womens underwear.

Thus, what began in the 1960s as a bit of surrealistic, Allen Ginsberginspired irony, apparently transformed into a resigned, post-9/11 cash grab, a cynicism that is difficult to reconcile with the sincerity and authenticity of his recorded music during this era, with its tangible reverence for that old, weird America (in Greil Marcuss phrase). As ever with Dylan, it remains difficult to determine if this recent willingness to participate in corporate America, an institution which he once decried as an affront to the authenticity of the American tradition, is in fact a tongue-in-cheek critique of the times in which we live, that the Boomers who once so tenaciously clung to his every word as a new gospel meant to free them from the chains of oppression were now willing participants in their own oppression, if not actively responsible for it. Is Dylan in his own not-so-subtle way criticizing or chastising his generation for their apparent hollow, self-centered idealism, their empty rhetoric of free love? Is this the same irony and surrealistic jest that infused his mid-1960s persona? Was he saying that the Cultural Revolution failed, crushed under the weight of its own hubris and smug self-satisfaction? That Dylans The Times They Are a-Changin played over a commercial for a bank and an insurance company seems almost to be a slap in the face to these so-called flower children, a final rejection of a culture which long misunderstood him, and had wrongly claimed him as a spokesperson, whose ideals he perceived as fake, unconvincing, self-absorbed, self-serving, and self-aggrandizing. Seen in this light, Dylans embrace of capitalist culture is perhaps not so much a resignation as it is a final rejection of a generation whose voice he did not want to represent. For, as the essays in this present volume argue, Bob Dylans voice is not the voice of a single postwar American generation, but rather a voice that is in many ways outside time, an American voice that derives from a rich musical tradition, from folk music to rock and roll, from Tin Pan Alley to bluegrass, from jazz to Western swing, from blues to ballads. It is, moreover, a uniquely poetic voice, and one that brings with it a lyrical tradition that stretches back to the French