I n 1737, the French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire, in a letter to the future Prussian King Frederick the Great, stated that history can be well written only in a free country. In 2016, the events that gave rise to our own free country were brought into strong focus, as Irish society commemorated the centenary of the Easter Rising.

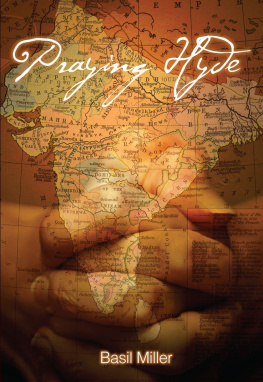

In the run-up to this significant anniversary, historians were prolific in assessing the momentous actions and the major personalities at the forefront of Irelands struggle for nationhood. One figure, however, was largely conspicuous by his absence Douglas Hyde.

Though Hyde was one of the most consequential of Irishmen, he is today very much a forgotten patriot. His public career has been given scant attention by historians, even though Hyde had arguably done more than any other individual to shape a distinct Irish identity and to encourage Irish people to regard themselves, in his own words, as a separate nationality. His cultural proselytising precipitated the political revolution from which Irish sovereignty flowed.

Exactly 200 years on from Voltaires musings about the drafting of history in a sovereign nation, the 1937 Constitution became the embodiment of the fullest form of Irish independence. The most important innovation in this new Constitution was the establishment of the office of President of Ireland as the effective head of state. Douglas Hyde would hold the distinction of being the first such office holder.

In the first year of Hydes term, Harry Kernoff, a leading Irish modernist painter, created a stamp design linking George Washington and Douglas Hyde as the respective first presidents of their nations. This graphite sketch is still available to view in the National Gallery of Ireland. Washingtons endeavours, on behalf of the nascent United States, earned him the sobriquet of Father of Our Country. In truth, such an accolade could also be applied to Douglas Hyde, given his work in preserving and promoting a distinct Irish national identity and subsequently as Irelands first first citizen.

In America, Washingtons work as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army and later as first President has secured him a rich historical legacy. Apart from the American capital being named in his honour and Presidents Day, the official observance of his birthday, still being a national holiday, George Washington has more places in the United States named after him than any other individual. A 2013 survey of the Census Bureaus geographic database found that Americas first President has ninety-four population centres called after him and 127 population centres where his name is found within a longer name.

In comparison to George Washington, Irelands first President fares much more modestly. Hydes image briefly decorated the Irish 50 note from 1995 until 2002, when the punt was replaced by the euro. Of the very few public locations named after the first Irish President, arguably the best-known is the Douglas Hyde Gallery, a publicly funded contemporary art gallery, which opened in 1978, in the grounds of Hydes alma mater of Trinity College Dublin. Irelands reluctance to remember the service of past presidents is, perhaps, somehow encapsulated in an unfair and ungenerous joke, partly aimed at Hyde, told by a Fine Gael TD. In 1973, Oliver J. Flanagan suggested to his partys Ard Fheis that the reason why there were no streets named after any former Irish President was because there was no road long enough and no road crooked enough in Ireland to suit that purpose.

If apathy is, to paraphrase the Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, a vice worse than anger, then Douglas Hydes legacy has been particularly ill-served by Irish historians. In the sixty-seven years since Hydes death, only two full-scale biographies of Irelands first President have been written. The first, written by two American professors of English and Comparative Literature, was published in 1991. However, the general indifference that Irish historians as a class have shown to Hydes career belies the significance of his contribution.

Patrick Pearse, the titular head of the Easter Rising, seemed to understand intuitively the seismic impact that Hyde and the establishment of the Gaelic League would have on the course of Irish separatism. In 1914, Pearse wrote: the Gaelic League will be recognised in history as the most revolutionary influence that has ever come into Ireland. The Irish Revolution really began when the seven proto-Gaelic Leaguers met in OConnell St The germ of all future Irish history was in that back room.

Pearse was also quick to praise Hydes influence on him personally, the loyalty he inspired and also the leadership he had provided in safeguarding Irelands culture. A year previously, Pearse had written: I love and honour Douglas Hyde. I have served under him since I was a boy. I am willing to serve under him until he can lead and I can serve no longer. I have never failed him. He has never failed me I can speak to him at once as friend to friend and as loyal soldier to loyal captain.

Ultimately, however, Pearse and Hyde would bitterly fall out, as the former embraced militant separatism at the expense, in Hydes view, of cultural inclusiveness. After resigning from the presidency of the Gaelic League in 1915, in a scathing reference to Pearse and his supporters, Hyde said that these people queered the pitch and put an end to my dreams of using the language as a unifying bond to bring all Irishmen together.

In post-independence Ireland or, to borrow Voltaires phrase, in our own free country, the writing of Irish history has tended to focus predominantly on those who opted for the militant path in the formative years of 1914 to 1923. Our process of commemoration also seems to have developed almost a hierarchy in the national pantheon with more attention being given to those who took up arms in the cause of Irish freedom than to those who provided the intellectual basis for a separate state. This is not a new phenomenon born out of the understandable emotion generated by the centenary of the Easter Rising. Official Irelands non-recognition of Douglas Hydes legacy was an issue that long rankled with his family. As far back as 1972, Hydes daughter Una Sealy remarked in an interview, I have often thought if he had killed people he would have been considered great, but because he was such a gentle, refined person, no one bothered about him. He has been ignored for a long time. They left his grave twenty-three years without attending to it.