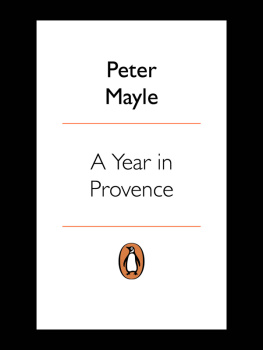

Hughes

South of France

only two hundred and fifty copies printed.

"I informed my friend that I had just received from England a journal of a tour made in the South of France by a young Oxonian friend of mine, a poet, a draughtsman, and a scholarin which he gives such an animated and interesting description of the Chteau Grignan, the dwelling of Madame de Sevign's beloved daughter, and frequently the place of her own residence, that no one who ever read the book would be within forty miles of the same without going a pilgrimage to the spot. The Marquis smiled, seemed very much pleased, and asked the title at length of the work in question; and writing down to my dictation, 'An Itinerary of Provence and the Rhone made during the year 1819, by John Hughes, A.M. of Oriel College, Oxford,'observed, that he could now purchase no books for the Chteau, but would recommend that the Itineraire should be commissioned for the Library to which he was abonn in the neighbouring town,"Sir Walter Scott's Quentin Durward.

Thomas White, Printer, Johnson's Court.

PREFACE.

It has been the Author's object to render the following volume a companion to persons visiting the country described. He has therefore not so much studied to compile from known books of historical reference, as to answer those plain and practical questions which suggest themselves during an actual journey, and to enable those whose time is limited, and who wish to employ it actively, to form the necessary calculations as to what is to be seen and done. The best points of view, and the parts which may be passed over rapidly, are therefore specified, as well as the places where good accommodation are to be expected, or imposition to be guarded against.

The subjects of the Illustrations will be mentioned in the course of the Itinerary, for the information of collectors, of whose notice it is trusted they will be rendered worthy by the well-known talents of Mr. Dewint and the Messrs. Cookes.

PARIS TO ROCHEPOT.

No one, I imagine, ever yet left an hotel in a central and bustling part of Paris, without feeling the faculty of observation strained to the utmost, and experiencing a whirl and jumble of recollections as little in unison with each other as the well known signs of that whimsical city, the Buf -la-mode, (with his cachemire shawl and his ostrich feathers) and the Mort d'Henri Quartre. The contrasts and varieties of the grave and gay, the affecting and the burlesque, the magnificent and the paltry, which exist and may be sought out in abundance in every great capital, are perhaps more vividly concentrated at Paris than any where else, and brought with less trouble under the eye of those whose spirits or leisure may not allow them to mix in society. In London every thing wears a busy uniform exterior, varied only by the apparition of a Turk, a Lascar, or a Highlander; and home appears to be the place reserved for the development of character: but in Paris, from the fashion of living almost in public, and the freedom which every one enjoys of following his own taste in dress or amusement without notice, the history of most individuals appears to a certain degree written on their exterior; and a morning's walk brings you in contact with all the diversities of character which rapidly succeeding events have created. The old beau, with the identical toupet of 1770; the musty, moth-eaten nondescripts sometimes seen at the mass of Notre Dame, which remind you of a still earlier period; the faded royalist, with a countenance saddened by the recollection of former days; the ex-militaires, whose looks own no friendship with "the world or the world's law;" the old bourgeois riding in the same roundabout with his grandchildren, and enjoying the jeu de bague as cordially,revolve in succession like the different figures in a magic lantern, while the place of Punch and Pierrot is supplied by a host of laborious drolls and gens l'incroyable. The various members of this motley assemblage appear also more distinct from each other, as connected in the recollection with places so strongly marked by historical events, or bearing in themselves so peculiar a character:the place Louis Quinze, the grim old Conciergerie, the deserted Fauxbourg St. Germain, with the grass growing in its streets; the Place de Carousel, the Boulevards, and the Catacombs, the Palais Royal and the Morgue.

To attempt, however, to say any thing new of a place so well known and so fully described as Paris, would be as superfluous as to write the natural history of the dog or cat. The peculiarities of such animals are continually striking one in new and amusing points of view; but verbal delineation has already done its utmost in acquainting us with them. In like manner, every thing relating to Paris, and illustrative of it at a period of interest which probably will not arise again for centuries, has been already made known in Paul's admirable letters, in poor Scott's powerful but unmerciful satire, and finally in a host of books, booklings, and bookatees, teaching us how to spend any period of time at Paris from three to three hundred and sixty-five days; how to enjoy it, how to eat, drink, see, hear, feel, think, and economise in it. Kotzebue has devoted sixty pages to its bon bons and savories; others more modestly give you only a diary of their own fricasseed chicken and champagne, and information of a still lower sort is supplied by the delectable Mr. Hone, for the instruction of our Jerries and Corinthian Toms. I shall commence dates, therefore, from the 26th of April, on which day we quitted the Htel de l'Europe, Rue Valois, not sorry to obtain a respite from sounds and sights.

Though in such a country as Tuscany, where every furlong of ground affords a new and rich subject for the pencil, the voiture mode of travelling is preferable to posting; yet no one, I think, would recommend it in traversing the tedious interval which separates Paris from the southern provinces. We had adopted this species of conveyance from the idea that it would afford more leisure for observation to those of the party to whom France was new; but we found in reality that by subjecting us to a dependence on hours, it diverted our attention from those places where we might have spent half a day to advantage, and familiarized us only with one branch of knowledge,the merit and demerit of most of the inns on the roads, whose characters I shall not fail to give as we found them. Homely as this species of information may be, I have often regretted the want of it beforehand; and concluding that others may be of the same opinion, I shall therefore afford it as far as I am able: premising, that it is as well not to vary, on this or any other road, from the practice of ascertaining beforehand the rate of the aubergiste's charges. The traveller's first impulse certainly is to save himself trouble, by paying whatever is demanded, and not to expend time and attention on a series of petty disputes, which make no great difference in his travelling expenses. There is, however, in all or most of those who are fitted to conduct the business of life, a feeling of shame at being outwitted even in trifles, which naturally rebels against this easy mode of proceeding, and inclines one rather to take the trouble of asking a few questions, than to be laughed at as a