Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

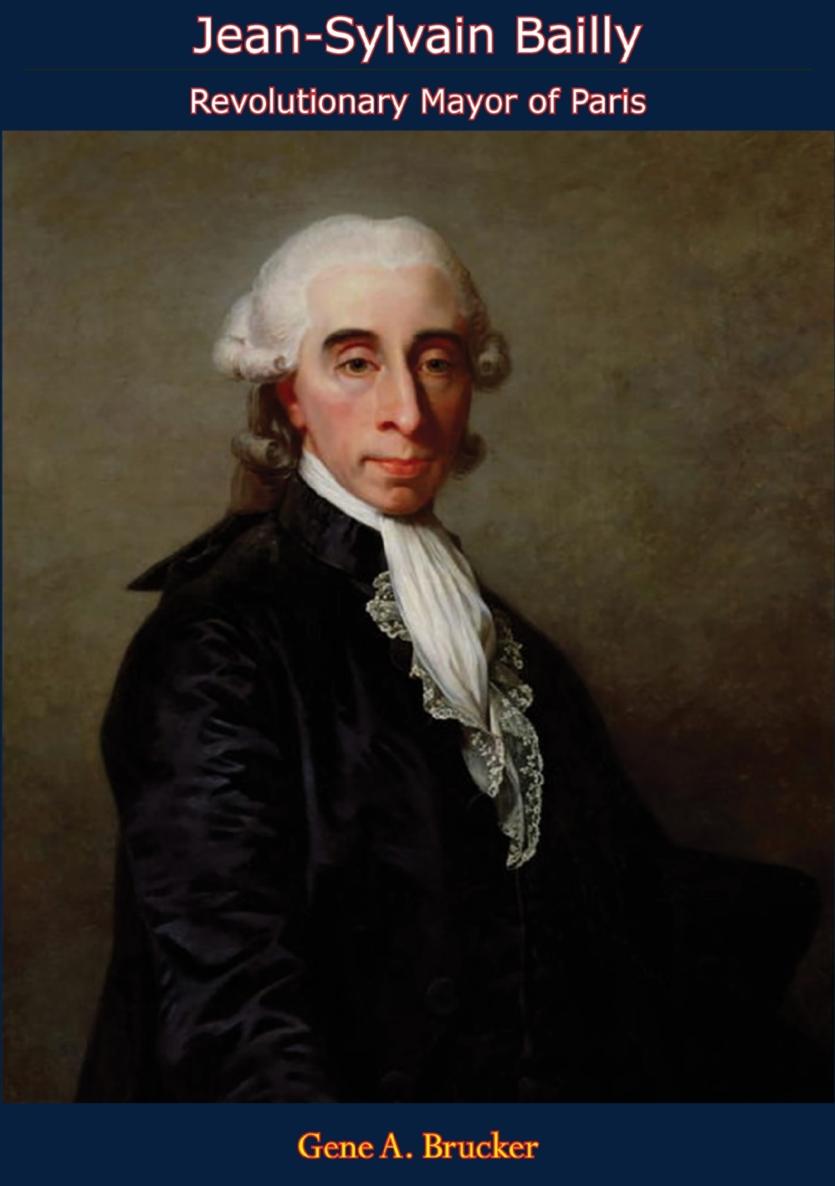

JEAN-SYLVAIN BAILLY

REVOLUTIONARY MAYOR OF PARIS

BY

GENE A. BRUCKER

PREFACE

IT IS CHARACTERISTIC of great revolutions that they are initiated by moderate men, who desire only limited reforms and who are most reluctant to resort to violence to obtain their ends. So began the French Revolution, and such a moderate was Jean-Sylvain Bailly, who, as mayor of Paris during the years 1789-91, struggled to maintain a balance between the two extremes of radicalism and reaction. He failed and paid for his failure on the guillotine. A study of his mayoral regime throws interesting light on these moderates in the early days of the Revolution, their character and aims, the problems which faced them and their attempts to solve them, the manner in which they strived to keep themselves in power, and how they failed. The question of why they failed is an open one, and perhaps cannot be answered. Bailly and his colleagues were not men of superior ability, but had they been giants instead of men, one is tempted to believe that the great storm which they had unleashed would have overwhelmed them.

I must acknowledge the great debt which I owe to Professor Raymond P. Stearns, who supervised this manuscript when it was being prepared as a thesis for a masters degree at the University of Illinois, and who for nearly a decade has been an inspiring teacher, a helpful counselor, and a true friend.

GENE A. BRUCKER

Oxford, England

CHAPTER ONESavant to Mayor

DESTINED TO BECOME one of the first heroes of the French Revolution, Jean-Sylvain Bailly, astronomer and academicien, was born and reared in the place of Versailles, in the stronghold of the ancien rgime. His father held the position of court painter and custodian of the royal art collection at Versailles, an office which had been in his family for a hundred and fifty years. An artist of some skill, the elder Bailly endeavored to impart his knowledge of painting to his young son. However, the youths propensities were of a more technical nature, and he profited from a curious bargain in which he received instruction in calculus from a certain M. de Moncarville, whose son in turn was taught design by Bailly pre. {1} Although he excelled in mathematics, young Bailly also had literary ambitions. While still only sixteen, he exhibited two of his dramatic works to the playwright Lanoue, who suggested that he throw them into the fire. {2} After this discouragement, Bailly returned with increased ardor to scientific pursuits. Attracted to the study of astronomy, he placed himself under the tutelage of the noted Abb de la Caille. He established his reputation quickly, and for three decades he devoted himself to scientific research and publication. On the eve of the Revolution, he was one of the most prominent astronomers in France and was known and respected by scientists throughout Europe.

In addition to his scientific writings, Bailly produced numerous works of a biographical nature, loges as they were called, designed primarily to promote the authors entrance into various learned societies. In Baillys case they succeeded very well; he was elected to three of the foremost scientific and literary academies in France. In the decade before the Revolution, he published a monumental history of astronomy, his best known work. {3} Bailly proposed the theory that scientific studies originated in India. He also developed the hypothesis that the lost civilization at Atlantis had flourished on an island which had sunk into the sea somewhere in the north polar region. Voltaire received this work with approval but questioned his theory of the origin of the study of science. Bailly printed the letters which he had received from Voltaire, together with a series of letters which he wrote in answer to Voltaires question. He later published another work, elaborating his theories on the origins of science. {4}

Bailly was a popular figure in the scientific circles and the salons of Paris. Franklin came to see him at his home in Chaillot in 1777, and Arago states that the American went away much impressed with Baillys ability to remain silent, a trait singularly unique for a Frenchman. {5} Bailly was a frequent visitor at the home of the artist Curtius, where some of the foremost savants of the day gathered regularly. {6} His relations with DAlembert and Condorcet were unfriendly because of some machinations in the Acadmie des sciences, as a result of which Condorcet received the post of permanent secretary which Bailly coveted. DAlembert had previously been on good terms with the young astronomer, advising him to write loges to prepare for his entrance into the academies. According to Condorcet, Baillys literary works were remarkably mediocre, possessing all of the beauties that it is necessary to avoid in writing. {7} It was with the aid of the naturalist Buffon that Bailly was elected to the French Academy in 1783, but the astronomer exhibited his characteristic independence later when he broke with Buffon over the choice of an Academy nominee. {8}

On the eve of the Revolution, Bailly was living in Chaillot, a residential section of Paris, enjoying his reputation as a distinguished scholar. In addition to his scientific studies, he occupied himself with the affairs of the three societies in which he held membership. He regularly attended the meetings of the French Academy, and in 1786 he served a term as chancellor of the Academy. {9} In 1787 he had married a widow to whom he remained very attached all his life. His physical appearance was unprepossessing; he was tall and thin, and his visage reminded one observer of a horses head. {10} Contemporary descriptions emphasize his tolerance and good nature, his air of serenity and natural dignity, his unimpeachable honesty.

Bailly, already well known to the intelligentsia and the court circles of Paris, became introduced to the bourgeois elements of the city through his work on various royal commissions. He was secretary of one group which investigated the curative powers of animal magnetism as propagandized by the German physician Mesmer. Baillys report summarizing the findings of the commission impressed the logical-minded by its rational treatment of a controversial question, although it was condemned by Mesmers more fanatic adherents. {11} His reputation among the Parisian populace was further enhanced as a result of his work on commissions which investigated the Htel Dieu, the citys largest hospital, and the slaughter houses of the city. {12}

Save for material in his Mmoires , there is little information on Baillys political views on the eve of the Revolution. {13} He was obviously deeply influenced by the political theories of the Age of Reason. Morellet lists Bailly as one of the revolutionary members of the French Academy, but Morellets characterizations are biased by his monarchist proclivities. {14} Bailly was certainly dissatisfied with the autocratic and irresponsible French monarchy. Besides being extremely critical of the Calonne and Brienne ministries, he castigated the Assembly of Notables which met in 1787 for its preoccupation with its own interests. He extolled Necker and the king as the men responsible for calling the Estates General, and thus for providing the French nation with the means to recover its rights. His political ideal, which he held throughout the revolutionary era, was a constitutional monarchy, with authority divided between the king and a representative assembly.