Chapter XI. The Unknown Lands South of the HismRuins of Shuwk and Shaghab.

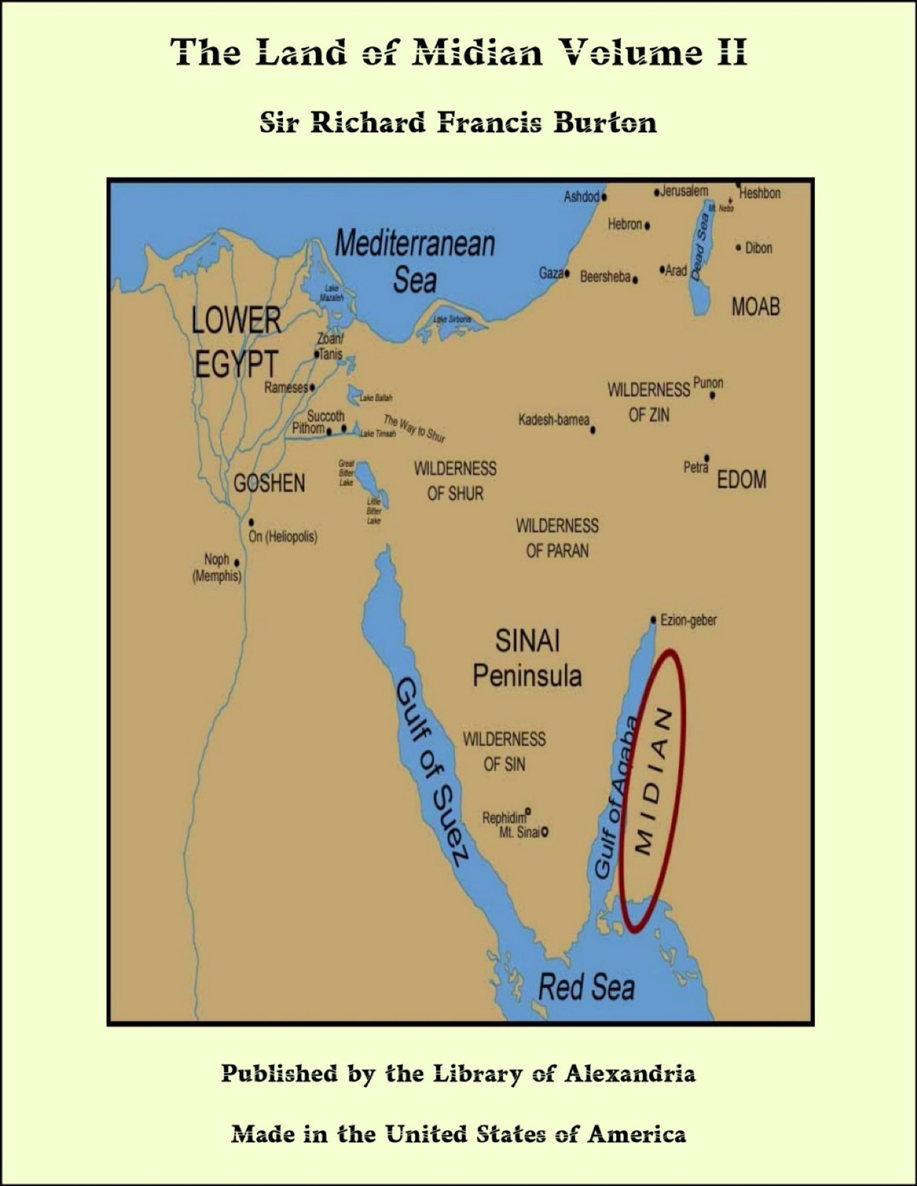

We have now left the region explored by Europeans; and our line to the south and the south-east will lie over ground wholly new. In front of us the land is no longer Arz Madyan: we are entering South Midian, which will extend to El-Hejz. As the march might last longer than had been expected, I ordered fresh supplies from El-Muwaylah to meet us in the interior vi Zib. A very small boy acted dromedary-man; and on the next day he reached the fort, distant some thirty-five and a half direct geographical miles eastward with a trifling of northing.

We left the Jayb el-Khuraytah on a delicious morning (6.15 a.m., February 26th), startling the gazelles and the hares from their breakfast graze.

The former showed in troops of six; and the latter were still breeding, as frequent captures of the long-eared young proved. The track lay down the Wady Dahal and other influents of the great Wady Sa'lwwah, a main feeder of the Dmah. We made a considerable dtour between south-south-east and south-east to avoid the rocks and stones discharged by the valleys of the Shafah range on our left. To the right rose the Jibl el-Tihmah, over whose nearer brown heights appeared the pale blue peaks of Jebel Shrr and its southern neighbour, Jebel Sa'lwwah.

At nine a.m. we turned abruptly eastward up the Wady el-Sulaysalah, whose head falls sharply from the Shafah range. The surface is still Hism ground, red sand with blocks of ruddy grit, washed down from the plateau on the left; and, according to Furayj, it forms the south-western limit of the Harrah. The valley is honeycombed into man-traps by rats and lizards, causing many a tumble, and notably developing the mulish instinct. We then crossed a rough and rocky divide, Arabic a Majr, or, as the Bedawin here pronounce it, a "Magrh," which takes its name from the tormented Ruways ridge on the right. After a hot, unlively march of four hours (= eleven miles), on mules worn out by want of water, we dismounted at a queer isolated lump on the left of the track. This Jebel el-Murayt'bah ("of the Little Step") is lumpy grey granite of the coarsest elements, whose false strata, tilted up till they have become quasi-vertical, and worn down to pillars and drums, crown the crest like gigantic columnar crystallizations. We shall see the same freak of nature far more grandly developed into the "Pins" of the Shrr. It has evidently upraised the trap, of which large and small blocks are here and there imbedded in it. The granite is cut in its turn by long horizontal dykes of the hardest quadrangular basalt, occasionally pudding'd with banded lumps of red jasper and oxydulated iron: from afar they look like water-lines, and in places they form walls, regular as if built. The rounded forms result from the granites flaking off in curved lamin, like onion-coats. Want of homogeneity in the texture causes the granite to degrade into caves and holes: the huge blocks which have fallen from the upper heights often show unexpected hollows in the under and lower sides. Above the water we found an immense natural dolmen, under which apparently the Bedawin take shelter. After El-Murayt'bah the regular granitic sequence disappears, nor will it again be visible till we reach Shaghab (March 2nd).

About noon we remounted and rounded the south of the block, disturbing by vain shots two fine black eagles. I had reckoned upon the "Water of El-Murayt'bah," in order to make an exceptional march after so many days of deadly slow going. But the cry arose that the rain-puddle was dry. We had not brought a sufficient supply with us, and twenty-two miles to and from the Wady Dahal was a long way for camels, to say nothing of their owners and the danger of prowling Ma'zah. In front water lay still farther off, according to the guides, who, it will be seen, notably deceived us. So I ordered the camp to be pitched, after reconnoitering the locale of the water; and we all proceeded to work, with a detachment of soldiers and quarrymen. It was not a rain-puddle, but a spring rising slowly in the sand, which had filled up a fissure in the granite about four feet broad; of these crevices three were disposed parallel to one another, and at different heights. They wanted only clearing out; the produce was abundant, and though slightly flavoured with iron and sulphur, it was drinkable. The thirsty mules amused us not a little: they smelt water at once; hobbled as they were, all hopped like kangaroos over the plain, and with long ears well to the fore, they stood superintending the operation till it was their turn to be happy.

Our evening at the foot of El-Ruways was cheered, despite the flies, the earwigs, and the biting Ba'zah beetle, which here first put in an appearance, by the weird and fascinating aspect of the southern Hism-wall, standing opposite to us, and distant about a mile from the dull drab-coloured basin, El-Majr. Based upon mighty massive foundations of brown and green trap, the undulating junction being perfectly defined by a horizontal white line, the capping of sandstone rises regular as if laid in courses, with a huge rampart falling perpendicular upon the natural slope of its glacis. This bounding curtain is called the Taur el-Shafah, the "inaccessible part of the Lip-range." Further eastward the continuity of the coping has been broken and weathered into the most remarkable castellations: you pass mile after mile of cathedrals, domes, spires, minarets, and pinnacles; of fortresses, dungeons, bulwarks, walls, and towers; of platforms, buttresses, and flying buttresses. These Girgir (Jirjir), as the Bedawin call them, change shape at every new point of view, and the eye never wearies of their infinite variety. Nor are the tints less remarkable than the forms. When the light of day warms them with its gorgeous glaze, the buildings wear the brightest hues of red concrete, like a certain house near Prince's Gate, set off by lambent lights of lively pink and balas-ruby, and by shades of deep transparent purple, while here and there a dwarf dome or a tumulus gleams sparkling white in the hot sun-ray. The even-glow is indescribably lovely, and all the lovelier because unlasting: the moment the red disc disappears, the glorious rosy smile fades away, leaving the pale grey ghosts of their former selves to gloom against the gloaming of the eastern sky. I could not persuade M. Lacaze to transfer this vividity of colour to canvas: he had the artist's normal excuse, "Who would believe it?"

The next morning saw the Expedition afoot at six a.m., determined to make up for a half by the whole day's work so long intended. The track struck eastward, and issued from the dull hollow, Majr el-Ruways, by a made road about a mile and a half long, a cornice cut in the stony flanks of a hill whose head projected southwards into the broad Wady Hujayl ("the Little Partridge"). This line seems to drain inland; presently it bends round by the east and feeds the Wady Dmah. Rain must lately have fallen, for the earth is "purfled flowers," pink, white, and yellow. The latter is the tint prevailing in Midian, often suggesting the careless European wheat-field, in which "shillock" or wild mustard rears its gamboge head above the green. Midian wants not only the charming oleander and the rugged terebinth, typical of the Desert; but also the "blood of Adonis," the lovely anemone which lights up the Syrian landscape like the fisherman's scarlet cap in a sea-piece. This stage introduced us to the Hargul (Harjal, Rhazya stricta), whose perfume filled the valley with the clean smell of the henna-bloom, the Eastern privetMr. Clarke said "wallflowers." Our mules ate it greedily, whilst the country animals, they say, refuse it: the flowers, dried and pounded, cure by fumigation "pains in the bones." Here also we saw for the first time the quaint distaff-shape of the purple red Masrr (Cynomorium coccineum, Linn.), from which the Bedawi "cook bread." It is eaten simply peeled and sun-dried, when it has a vegetable taste slightly astringent as if by tannin, something between a potato and a turnip; or its rudely pounded flour is made into balls with soured milk. This styptic, I am told by Mr. R. B. Sharpe, of the British Museum, was long supposed to be peculiar to Malta; hence its pre-Linnaean name (Fungus Melitensis). Now it is known to occur through the Mediterranean to India. Let me here warn future collectors of botany in Midian that throughout the land the vegetable kingdom follows the rule of the mineral: every march shows something new; and he who neglects to gather specimens, especially of the smaller flowers, in one valley, will perhaps find none of them in those adjoining.