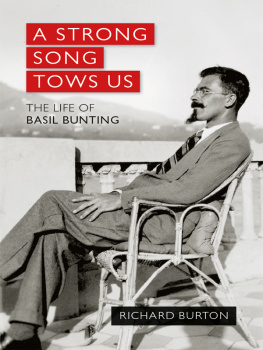

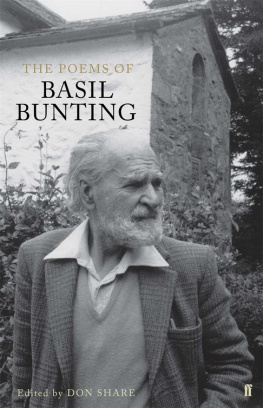

A STRONG SONG TOWS US

THE LIFE OF BASIL BUNTING

Richard Burton

Copyright Richard Burton, 2013

The right of Richard Burton to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2013 by

Infinite Ideas Limited

36 St Giles

Oxford

OX1 3LD

United Kingdom

www.infideas.com

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of small passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. Requests to the publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, Infinite Ideas Limited, 36 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LD, UK, or faxed to +44 (0) 1865 514777.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-909652-49-1

Published in North America by Prospecta Press

P.O. Box 3131

Westport, CT 06880

(203) 903-5176

www.prospectapress.com

ISBN 978-1-909652-49-1

Brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.

Designed and typeset by GRID

Printed in Britain

To Elizabeth, Jamie and Jo.

This spuggy has fledged.

INTRODUCTION

Fifty years a letter unanswered;

A visit postponed for fifty years.

She has been with me fifty years.

Briggflatts

Brigflatts, 6 March 2013. The snow filling this tiny Quaker burial ground in the far north of England is delivered horizontally. It arrives on a gale that picked up its wings somewhere north of Franz Josef Land. It is barely possible to make out the simple headstones in the blizzard. Not a soul stirs. There is no birdsong. In this weather this is one of the bleakest places in Britain.

One hundred years ago, in March 1913, a thirteen-year-old boy called Basil Bunting stood in this graveyard for the first time. How little he could have known then how the spirit of this place would give him his own wings for seventy more years of what was, by any standards, an astonishing life. Along the way he was a conscientious objector, prisoner, artists model, journalist, editor, sailor, balloon operator, interpreter, wing commander, diplomat, spy and, above all these, a poet. It wasnt just Brigflatts spirit of place that buoyed him up through these adventures. The clink of its stonemasons chisel shaped his art. Meditation in the Quaker Meeting House shaped his philosophy. His love for the stonemasons young daughter, Peggy Greenbank, stayed alive through fifty years of separation. It was, as we shall see, one of the great love stories of the twentieth century.

* * *

A Strong Song Tows Us began three years previously. As I read Descant on Rawtheys Madrigal in the Upper Reading Room of Oxfords Old Bodleian library I wondered if I really wanted to write this book. As I turned the final page I saw that it was a limited edition, signed by its authors, Jonathan Williams and Bunting himself. I found myself staring at Buntings signature it was as intricately patterned and layered as a Lindisfarne illumination. I tried to follow its loops and curlicues. Like the bull that bellows us into Briggflatts it was ridiculous and lovely.

But what was it for? Bunting, for whom the slightest superfluity was an artistic failure, was one of the great parers of twentieth-century letters, a ruthless editor of his own work. He famously urged writers to use a chisel rather than a pen so as to load each individual mark with its maximum freight of meaning and intensity. I was familiar enough with his habitual signature, a flowing single B with a dot. How could Bunting of all writers represent himself with this rococo fantasy? I tried to follow the ebbs and flows of his script as extravagant Bs rippled into almost formless Ns and then lurched away in search of a crowning T and plainsong G. It must have taken him longer to sign these books so generously than to complete the interviews they contain. It was, of course, entirely unlike his normal signature. My foreboding about writing a life of Bunting gathered; its subject would have despised the entire enterprise.

Descant on Rawtheys Madrigal is a transcript of interviews that Williams conducted with Bunting when the poet was in his mid-sixties. Williams wanted Bunting to recall his life but his interviewee was clearly reluctant. The book begins with a statement from Bunting: Jonathan, I am surprised at you. What the hell has any of this to do with the public? My autobiography is Briggflatts theres nothing else worth speaking aloud.

For Bunting Briggflatts was autobiography enough. He scorned any kind of life writing as a channel into his or anyone elses art. For Bunting you cant understand a poem just by knowing the historical events that charge it. You cant even understand a poem by reading it. The only way to uncover the mystery is to hear it. Follow the clue patiently and you will understand nothing, he writes in Briggflatts. When Bunting read that line the pause he inserted before the final word is pregnant with contempt for clue followers, patient or otherwise.

My concern deepened as I read those of Buntings letters that survive in various archives in the US and UK. Is it altogether decent to write a biography of someone who loathed the idea of one, who destroyed all the letters he received and who urged his friends to destroy his own in order to make a project like this as difficult as possible?

I was encouraged, however, by the benign part of the benign contempt I had detected. After all, Bunting had participated fully in Descant on Rawtheys Madrigal and approved publication. It reminds me of Yeats dismissal of Friedrich Von Hgel at the end of Vacillation. It is a sympathetic kind of grumpiness. In any event Bunting himself was not above using biography in pursuit of what he saw as a good cause. His introduction to his edition of the poems of Joseph Skipsey begins with a detailed account of Skipseys life and he confesses to having sought out surviving family members for their memories. He did this because he recognised that the way to interest people in the work of a neglected poet is to tell his story, not to harangue them.

My other plea of mitigation is that I consciously use Briggflatts, Buntings verse autobiography, as the spine of this life. Brigflatts sits high in the Pennine mountains, which separate the east and west of northern England and are often described as the countrys backbone. (The addition of the extra g in Buntings title seems to be the poets attempt to Norse-up his dossier.) Buntings poem acts as the Pennine Chain of this book, holding its landscape together on the one hand and, I hope, providing vistas that help us see the hinterland of Buntings work.

Next page