Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For the suns that rise on the horizons weve yet to see, for my brothers and sisters, my sons and daughters.

For my father, Bee Yang, who sings his lonely songs so that we may hear the trembling of the still, fluttering heart.

Kwv txhiaj is, in the words of Ralph Ellison on American blues,

an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in ones aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-cosmic lyricism. As a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.

* * *

Kwv txhiaj songs can be duets: the voices of fathers and daughters coming together, different verses within the same song, stanzas in the same poem.

My father would never describe himself as a poet. In Laos, he was a fatherless boy. In Thailand, he was a refugee waiting in the dust. In America, he is a machinist. Through it all, he has been a poor person yearning for a father and living to be one.

My father is Chue Mouas husband and the father of seven children, five girls and two boys. My father says that on his gravestone he wants it known that his wife and his children are his lifes work. He would love it if we could add: All of Bee Yangs children became good people.

I am the only person I know who describes my fathers work as poetry. I am not referring to the pieces of hard metal he polishes, the rough edges he makes smooth, the coarseness he evens into shine. I am talking about the songs he composes, day and night, in Hmong, our language, his kwv txhiaj .

My father is not a writer. He does not write down his compositions. He is a singer. He sings them.

It has taken me a long time to gain the courage to call my fathers work poetry. For much of my life I have described my father to the world as a machinist, not as the poet I know him to be. I didnt have a way of conveying how being my fathers daughter has taught me not how machines work but how the human heart operates.

I grew up hearing my father digging into words for images that will stretch the limits of life for my siblings and me. In my fathers mouth, bitter, rigid words become sweet and elastic like taffy. His poetry shields us from the poverty of our lives.

On the colorful woven plastic mat in the middle of our living room floor, we sit around my father. We look at the walls with him. The mold growing wild becomes the backdrop of the beautiful paintings we see on television, the peak of this mountain, the descent of that river, the sliver of tree that clings to life on the edges of the rocks, open and exposed. We point at the things we did not see before our fathers words gave them shape, alternatives, possibilities. My brother Xue sees a crane at the rivers edge. Sib Hlub points to the sky with its cloud families, gray and rumbling, and whispers of bad weather approaching. For a moment, we are living in a priceless, ageless piece of art.

In the deep of winter, after months of unceasing cold, my father points outside our front window at the ice-covered mounds of snow shining in the bright sun, under a cloudless sky of blue, and says, Look at the garden of winter, the snow flowers are blooming today. My siblings and I leave our places by the big heater with its openings single blue flame, and we look out into a picture of winter we thought we had grown sick of. We blink against the shine. Beneath our lashes, in the sliver of open eyes, stars twinkle in the colors of the winter rainbow. The children marvel while my older sister Dawb and I take deep breaths and breathe foggy air onto the glass pane. We draw the flowers of early spring on the cold, wet glass with our fingers: buds of tulips and daffodils, the bursts of dandelions and fragrant lilac blooms. The sweet, clean scent of magnolia blossoms and the images of the flowering treesstocked with soft white, pink, pinkish-red, and purplish-white petalsremind us that warm weather and abundant flowers are coming our way. The world of winter becomes bearable in the promise of spring.

In perfect pentatonic pitch my father sings his songs, grows them into long, stretching stanzas of four or five, structures them in couplets, repeats patterns of words, and changes the last word of each verse so that it rhymes with the end of the next. He is a master at parallelism; the language is protracted, and the notes are drawn deep and long. The only way I know how to describe it as a form in English is to say: my father raps, jazzes, and sings the blues when he dwells in the landscape of traditional Hmong song poetry. Different shapes come forth from the dirty places, different possibilities are born in the shadows of our lives, and windows emerge in the places my brothers and sisters and I have only ever seen walls.

I grew up surrounded by my fathers words. They are familiar to me as the wind outside the thin walls of our old house across the different seasons.

In the cool of autumn, the wind carries the dry, crackling leaves along the sides of York Avenue. Empty cans roll along the broken cement walk and abandoned plastic bags fly with their ghostly goods. An occasional voice is carried in the wind, a brother looking for a sister as night falls, a baby crying for its mother, the bark of a hungry dog.

In the cold of winter, the wind blows the snow off the ground and waves of white come sweeping across our tiny stretch of lawn and hit the house in sprinklings of icy snow. Invisible streams of air seep through the cracks of the old windows and the smell of our rice-scented home swims in the currents of cold. Outside, the sound of police sirens resonates in the rippling, urgent winter winds.

In the warmth of spring, the wind transforms the empty parking lot by the corner Laundromat into a field of fallen petals as crab apple trees release their blooms and the hard pavement feels the soft brush of tender, ephemeral beauty. Wet rain falls into shattered concrete and the pools of black water lie still for the pink and white and red petals to swim in. The wind carries the voices of laughing children into our house as we watch the petals sway to and fro in the dark puddles across our street.

In the heat of hot summer, the green grass grows while the yellow dandelions die, and in the wake of their demise the wind carries their spirits and their seeds across open lots, rotting houses, small yards, littered avenues, and everywhere there are little parachutes of pollen floating away. Late into the night, we listen to the voices of friends and neighbors talking outside on their porches, hear the clinking of cans, turn our heads toward their laughter and their tears, and the wind loses its appeal for a season because the pull of people grows strong across the fertile green.

My father was a young man who carried on his broad shoulders hundred-pound sacks of rice while I ran fast as I could to open the front door lest he beat me there. Then came the season when there was no danger that my father would get there before me, when I stood with the door wide open, my fingers soft against the hard wood; I watched my father age with each sack of rice we bought and ate. My wait at the front door of our house grew long as my fathers steps grew heavier on the ground and his shoulders shook beneath the burden of feeding us.

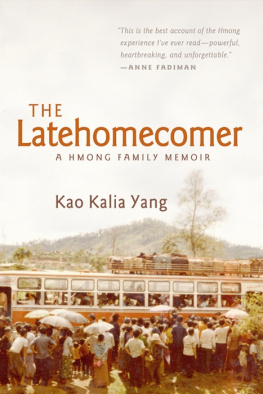

![Yang - The latehomecomer: [a Hmong family memoir]](/uploads/posts/book/165016/thumbs/yang-the-latehomecomer-a-hmong-family-memoir.jpg)