quilting.

alchemists mumble over pots.

into science. their science

freezes into stone.

I was born a stateless Hmong girl in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand. For the first six years of my life, I understood that the camp was only our holding center. We lived in the third sector, in the third subdivision, in room six, a small sleeping quarter I shared with my mother, father, and older sister. From the moment of my birth, the people who loved me told me that it was not my home. Home was once the tall mountains on the other side of the river. Home would one day be some foreign country on the other side of the ocean.

I had not experienced war myself, but I was surrounded by its consequences. The adults around me told me stories of what had happened in Laos. On the hot days when the sun blazed in the blue sky, beneath the shade of thatched roofs, I traced the scars on the adults I loved, ripples of rising skin, sunken flesh where bones should be. I knew their different cries in the dark of night, the nightmares from which they fought to surface each morning, the tired, empty look in their eyes, and the fear in me that perhaps the people I loved were broken inside. On paper, I was a refugee.

I looked the part. I was small for my age, thin and short, had big round eyes that peeked at the world from beneath my bangs with suspicious curiosity. I was a little creature, kept in a little cage. I was a child keenly aware of the dangers of a world in which I belonged to no nation.

When my family came to America and I was sent to school, I was placed in a class with many other refugee children, mostly Hmong like myself, but also Cambodian and Vietnamese. I was one of the youngest in a mixed-aged class. During art, some of the big students drew pictures of things they had seen before coming to America. A tall boy with watery eyes drew a picture of a thick green jungle, and then a single foot sticking out onto a dirt path. The foot looked heavy and stiff and blue, like a stone statue of a foot. The boy said that the foot belonged to his brother. Hed found his brother after an ambush. He hadnt had the courage to look into the heavy brush, to see if his brothers body was intact, to look at his face. The older children who had seen more than we had wanted to let their stories out, for us younger ones to carry the weight of their memories together with them. We were willing because they were like our older brothers and sisters, our mothers and fathers, aunts and unclesall those whod lived through the wars.

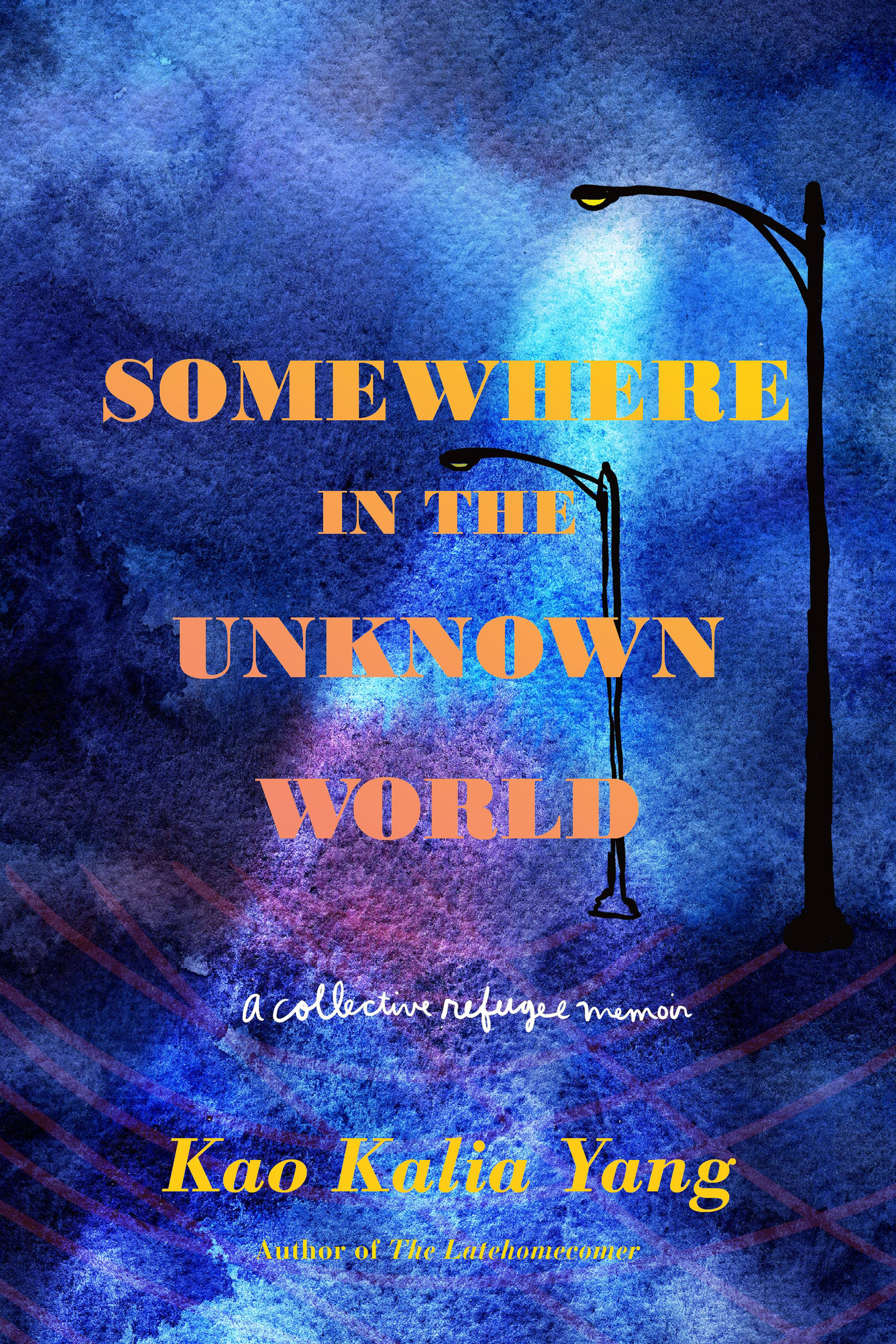

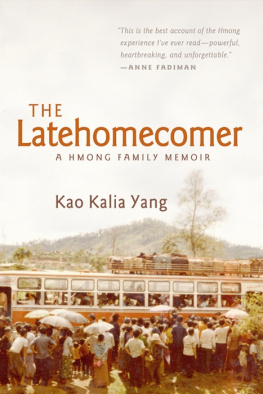

I have carried the stories of those around me all my life. I never thought that I would write them down, and I wouldnt have had my grandmother not died illiterate and fearful that the journey she had traveled in her life would be forgotten. So I told a story that much of America did not know, about a people who were new to the written form. Traveling across the country to speak about my book, from state to state, city to city, I met many refugee resettlement workers and refugees. I discovered how little we knew of each others lives and how the isolating loneliness many of us felt was a shared experience.

Other refugees asked me to tell their stories, but I wasnt ready. I was a young writer then, looking for legitimacy in literary America, in a genre dominated by white authors. I was struggling to build confidence and stand up for the Hmong and I could not fathom how I would carry the stories of other people. But, even then, I was bearing witness to the heartache and the yearning of refugee men and women wanting to be understood.

Over the past few years, I could not fail to see an America that was questioning its long history of refugee resettlement, an America that seeks to define itself by casting its vulnerable immigrants and incoming refugees to the margins of society. Greater than my fear of what I could not do was a growing need to convey the refugee lives around me, to show our shared understanding of war and hunger for peace, our vulnerabilities and strengths, and to offer our powerful truths to a country I love.

When the cold comes to Minnesota, it arrives quickly. On an October evening, the air feels particularly balmy. The colorful leaves of autumn sway in the dark wind and the moon, a sliver of a fingernail, hangs low in the heavens. Then, the next day, the world feels different. The air has turned crisp, and the soft yielding grass of yesterday is gone and covered with frost.

I have lived in Minnesota for more than thirty-two years. I understand the process of the changing seasons well enough. But even with this knowledge, each cycle of fall becoming winter strikes me as something new. My heart is never quite ready for the frigid wind that will seep through my clothes, skin, flesh, and bone. Without central heating, insulated walls, the buffer of a jacket, hat, scarf, and mittens, I wont survive. Winter is humbling in Minnesota.

Winter here prepared me for the work of writing this book. The endless days of gray gave me ample opportunity to reflect on my own journey and see that this once stateless child is here in Minnesota telling stories because I walked a broad margin of possibility; I met extraordinary people who gave me the gift of their experiences, which shaped my understanding and informed my conscience.

This book is an endeavor of the heart. I listened to each of the people represented here and then processed their stories slowly. I made a promise to myself: I would tell the story of every person I spoke to. Id too often witnessed members of my family and community recount their experiences, weeping as they returned to their past, only to have it live and die in the moment because the listeners deemed other stories more important. I didnt want to be that person. I then wrote each chapter, weaving in research to fill in the areas of the world Ive never been to, and then sent it on to the interviewee with a direct question, Is the story accurate? In the hopeful corners of my heart, I dream that Somewhere in the Unknown World will be received as an expression of my admiration for the individuals revealed here and that their stories will be helpful to their families and communities.

Somewhere in the Unknown World takes place in Minnesota, my home state. There are refugees from everywhere here, from wars past and present. In fact, the state is home to more refugees per capita than any other state in the nation. We have the highest concentration of Hmong and Tibetan in the country, the biggest populations of Somali, Karen, Burmese, Eritrean, and Liberian refugees. This much is known, but few know who we are or how we live. There are worlds within worlds, possibilities not visible, individuals who struggle and survive the unimaginable every day to be here.

![Yang - The latehomecomer: [a Hmong family memoir]](/uploads/posts/book/165016/thumbs/yang-the-latehomecomer-a-hmong-family-memoir.jpg)