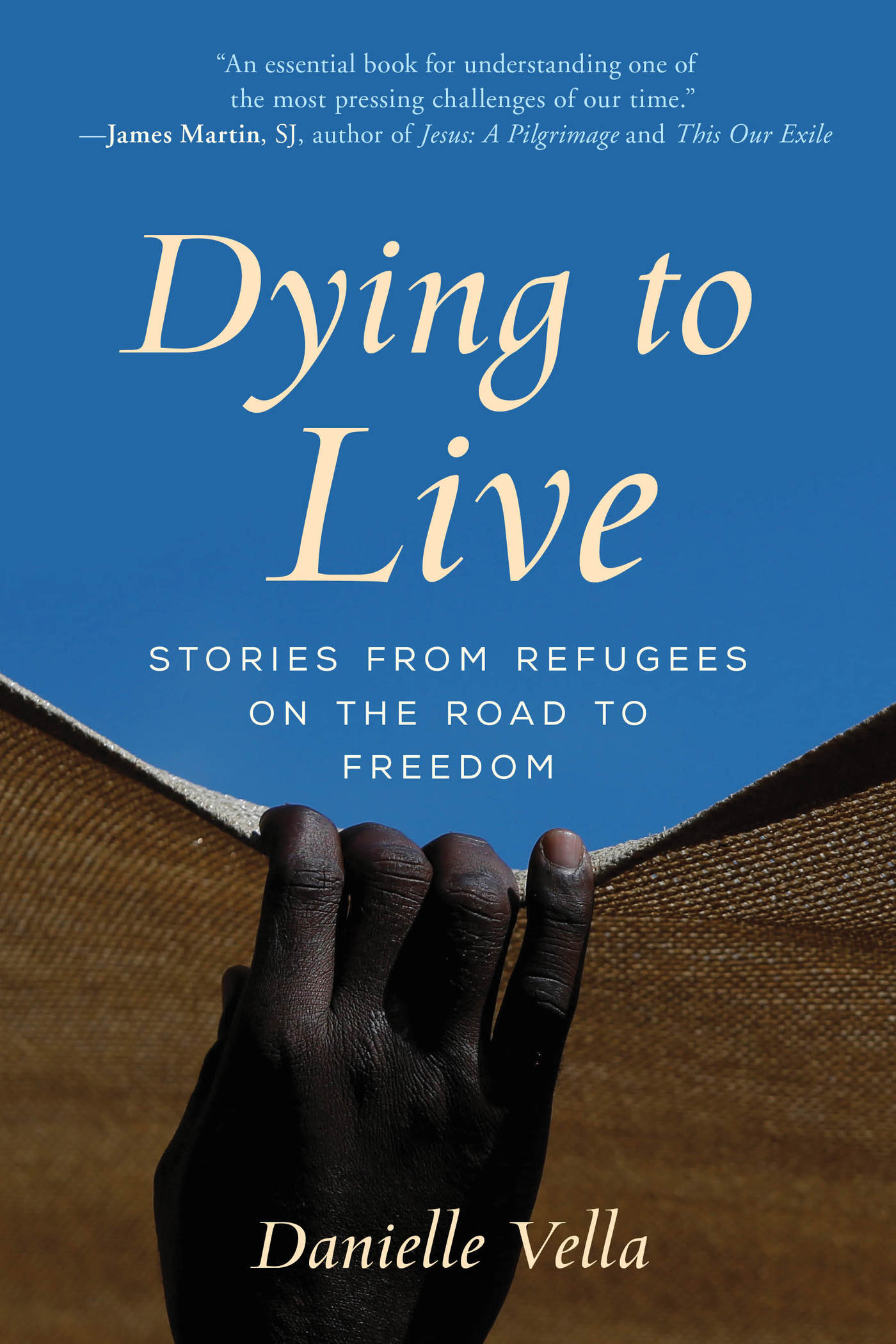

Dying to Live

Dying to Live

Stories from Refugees on the

Road to Freedom

Danielle Vella

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

https://rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom

Copyright 2020 by Jesuit Refugee Service

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952511

ISBN 9781538118450 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781538118467 (epub)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

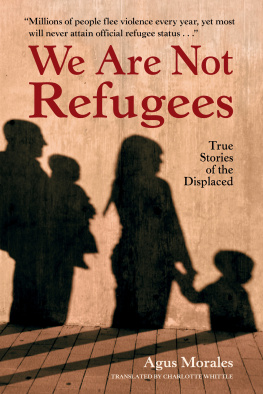

Cover image: A rescued refugee holds on to a tent on the deck of the Malta-based NGO Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) ship Phoenix as it makes its way to Pozzallo on the island of Sicily, Italy, April 6, 2017.

Preface

In this book, I primarily use the term refugees rather than migrants. There are diverse definitions of who qualifies as a refugee in the legal sense of the word. I have opted for the definition of de facto refugee offered by the Catholic Church and endorsed by the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS). This broad understanding of the word refugee embraces people who are forced to flee their home country to escape war and armed conflict, persecution, and/or natural disasters, as well as those who are victims of erroneous economic policy.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to each and every refugee who shared his or her story with me. Unfortunately not all are featured in this book because I ran out of space. But it was a privilege to listen to every one, and I wish you the very best in your journey to find life. Most of the names used in the stories are fictitious; however, some are the real names, used at the request of the protagonists.

I could only write this book thanks to the logistical and moral support of people working for the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) in the places I traveled to meet refugees. I will not name them for fear of leaving someone out. But you know who you are and I am endlessly grateful to you.

JRS is an international Catholic organization with a mission to accompany, serve, and advocate on behalf of refugees and other forcibly displaced persons. Unless otherwise specified, every time reference is made to a nongovernmental organization (NGO), that NGO is JRS and, in the case of Melilla, SJM (Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes). The same applies to the Welcome Network in France. The involvement of JRS in some of these stories gives an indication of the breadth of its mission, from offering legal aid to supporting schools to going on home visits in urban areas to being present in remote refugee camps.

There are a few exceptions. In Belgrade, local Serb NGOs run the two centers I visited and I thank them for their welcome and patience. In Melilla, I thank the sisters of Geum Dodou. And in the United States, specifically in San Diego, the resettlement agency referred to is the International Rescue Committee (IRC). I am indebted to the entire team and volunteers of the IRC in San Diego for their hospitality and enthusiasm to help me with this project. I am also in awe of their amazing work.

Part I

Flight

Chapter 1

Where Do I Begin?

Every story has a beginning. When Martin goes back to his, he mentions each member of his family by name, and remembers their home in South Sudan. Holding himself stiffly upright, Martin enunciates each word with deliberation: I had my father, David; my mother, Mary; my sister, Betty; and my brother, called Paul. My family was not rich but we were happy. In term time, Dad sent me to school in Uganda. Otherwise, Mum and I would go to the farm to work. My dad ran a small business, selling flour and rice, but now I dont know if he lives or not.

Mustafa, a tailor from the city of Raqqa in Syria, dates his familys story to a time when life was beautiful in their countryin his eyes, at least. The father of five says, School was for free. Everything was cheap. We liked to have children because we didnt have to worry about raising them. Syria was really wonderful. Salma also comes from Syria and she echoes rose-tinted memories of what was. Like Mustafa, she remembers being free from financial worries. We had a good life. My husband and his brothers worked at a biscuit factory that belonged to the family. We lived in our own house and were paying a bank loan for it. Reminiscing about the family picnics that were a weekly treat, Salma whips out her phone and scrolls until she finds a photo of her home: a terraced house on two floors, gaily painted in pink with a white diamond pattern.

Martin, Mustafa, and Salma are telling the stories of how they became refugees. The way they start reveals just how much they have lost: family, work, dreams, and the simple joy of living. However, not all refugees trace their stories to a nostalgic time. Take Farid, whose life as a taxi driver in Afghanistan was packed with risk and fear every single day. Farids greatest cause of anxiety was that the Taliban viewed him suspiciously and dogged his every step. One night, a few minutes after he returned home from work, the Taliban knocked at his door and roughly accused him of being a government spy: If you are not working for the government, from where did you get money to buy a taxi? How can you travel to Kabul without security problems? Farid was unhappily aware that in that moment, they could kill me if they wanted and who would ever dare to ask why?

At some point, Farid decided that enough was enoughhe was sure his life was in dangerand he left Afghanistan. In other words, Farid became part of the worlds forcibly displaced population of 70.8 million, a statistic so massive that it drowns all those it counts in anonymity and oblivion. And yet each story is exclusive, a unique blend of circumstance, choice, and character. The moment of flight, and the events leading up to that fateful decision, are never the same.

Sometimes life changes from one minute to the next. War explodes in your face. Matthew was nineteen when the liberation war reached our place in South Sudan in 1989. The rebels appeared, very many people, shooting at us. Matthew and the rest of the town dropped everything and ran, with the rebels in furious pursuit. There was only one option: We had to cross the Nile. People crammed into canoes and paddled frantically with their hands to sweep through the water. Matthew recalls, We had to force ourselves into that small boat. When we were in the middle of the river, the boat capsized, and so we had to try our level best. One of the children drowned.

Sometimes, the proverbial straw breaks the camels back: something happens that makes the accumulation of violence, repression, poverty, and total lack of opportunity too hard to bear any longer. Khalid left the Gaza Strip after his family home was demolished: Death came to our door and we lost our home. Israeli forces bulldozed his neighborhood after Hamas militants fired rockets from there. We, people from the place, were against this because we knew wed have problems, says Khalid. But Hamas said they could do what they liked.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.