OTHER BOOKS BY MUTLU KONUK BLASING

Lyric Poetry

(2007)

Politics and Form in Postmodern Poetry

(1995)

American Poetry

(1987)

The Art of Life

(1977)

Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks.

Copyright 2013 by Mutlu Konuk Blasing

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopy, recording, digital media, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission to reprint or make photocopies and for any other usage should be addressed to:

Persea Books, Inc.

277 Broadway, Suite 708

New York, New York 10007

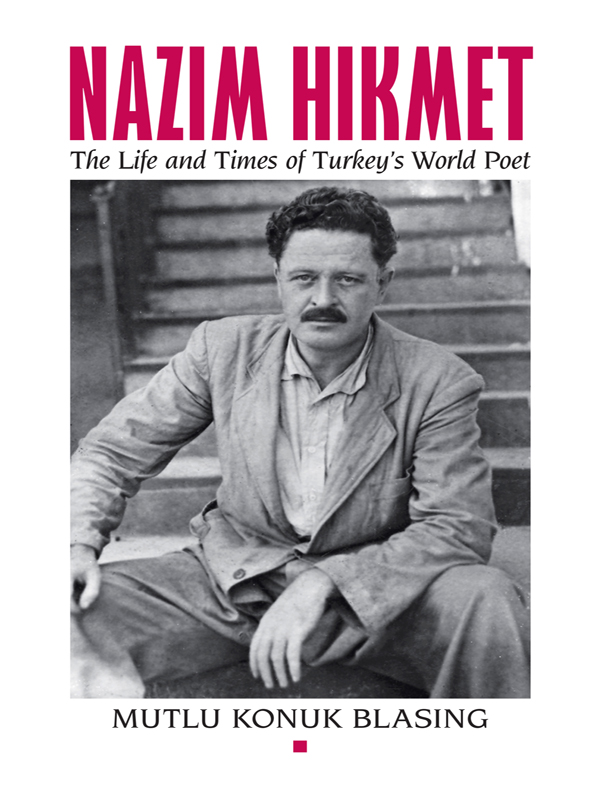

The publisher gratefully acknowledges Nzim Hikmet Kltr ve Sanat Vakfi, Istanbul,

Turkey, for permission to reproduce the photographs following page 108.

The Library of Congress has catalogued the printed edition as follows:

Blasing, Mutlu Konuk, 1944

Nzim Hikmet : the life and times of Turkeys world poet / Mutlu Konuk Blasing.First edition.

pages cm

A Karen & Michael Braziller book.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-89255-417-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-89255-445-4 (eBook)

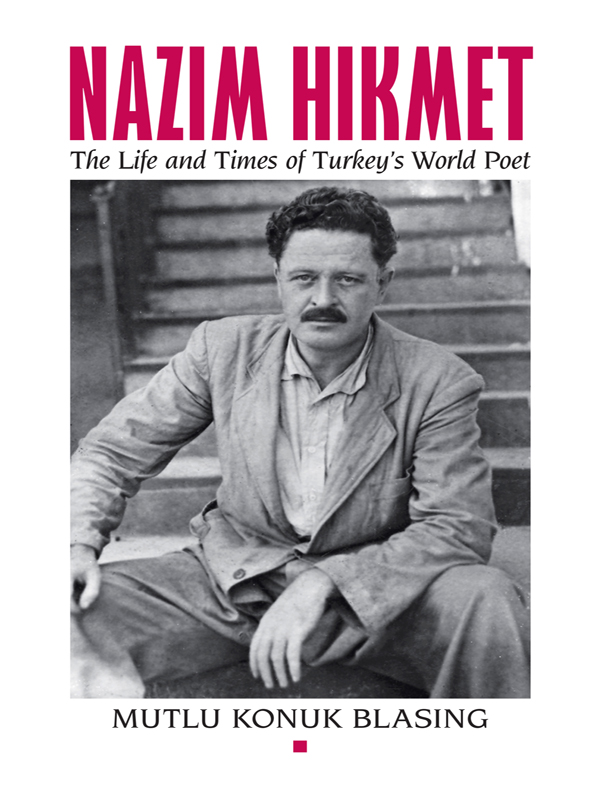

1. Nzim Hikmet, 1902-1963. 2. Poets, TurkishBiography. I. Title.

PL248.H45Z5928 2013

894.3513dc23

[B]

2012043694

Designed by Rita Lascaro

Printed and bound by Maple Press, York, Pennsylvania

First Edition

To Randy Blasing

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

MY NINETEENTH YEAR

PART I

AT LARGE: THE MAKING OF A POET (19021938)

PART II

IN DEEP: PRISON (19381950)

PART III

OUT FAR: EXILE (19501963)

IN 1965, the American poet Randy Blasing first introduced me to Nzim Hikmet in a French translation he discovered in the library at the University of Chicago. Hikmet had been so effectively silenced by the authorities in Turkey for so long that I had never even heard his name in my nineteen years of growing up there. The next year, Randy and I started down the road of giving voice to Hikmet in English and have continued on it to this day.

I could never have completed the five-year project of writing this book alone. I am indebted not only to Randy Blasing for his constant encouragement and unfailing good counsel but also to Azade Seyhan for her insightful suggestions and thoughtful advice on an early draft; to Gndz Vassaf for generously sharing his wealth of knowledge about Hikmet; to Kiymet Cokun of the Nzim Hikmet Foundation for her kind assistance; to the Brown University English Department for summer research grants that enabled me to draw on resources available only in Istanbul; to Jane Donnelly for making sure I dotted my is and crossed my ts; and to Karen Braziller and Persea Books, as perceptive an editor and as dedicated a publisher as I could ask for.

I am also grateful to the 2010 Mahmoud Darwish / Nzim Hikmet Conference at NYU/The New School for inviting me to present a paper, based on the section Scripting a Nation, that was subsequently published as Nzim: Bir Ulusun Senaryosu in Istanbul airi Nzim Hikmet Ho Geldin (Ankara: Ministry of Culture, 2010). I presented earlier versions of other sections in talks I was invited to deliver, in 2010, by the American Turkish Association of North Carolina at the Second Annual Nzim Hikmet Poetry Festival and, in 2009, by the Twentieth-Century Colloquium group at Yale University; the latter talk later appeared, much revised, as Nzim Hikmet and Ezra Pound: To Confess Wrong Without Losing Rightness in The Journal of Modern Literature (Winter 2010).

Turkish is phonetically transcribed, and every letter but one is pronounced:

a are

c journey

child

e effort

g game

silent; serves only to lengthen the preceding vowel

i ever

i in

j as in French j

o roll

as in German

shot

u full

as in German

The other consonants are pronounced as in English. There are no diphthongs, and circumflexes over /a/ or /u/ indicate a longer /a/ or /u/.

Unless otherwise credited, all translations from Turkish prose sources are mine, as are passages from Nzims poetry; poems and passages cited from Poems of Nzim Hikmet and Human Landscapes from My Country were translated with Randy Blasing. Translations from Russian sources are mine via Turkish translations.

I refer to Poems of Nzim Hikmet as PNH and to Human Landscapes as HL.

Following their first citation, I refer to all poems and plays by the English translations of their titles. Similarly, I refer to the following works by the English translations of their titles, even though they do not exist in English:

Alman Faizmi ve Irkilii [German Fascism and Racism]

Btn iirleri [Complete Poems; cited as CP]

Pirayeye Mektuplar [Letters to Piraye, 2 vol.; cited as LP, followed by the volume number]

Kemal Tahire Mahpusaneden Mektuplar [Letters to Kemal Tahir from Prison; cited as LKT]

Bursa Cezaevinden V-Nlara Mektuplar [Letters to V-Ns from Bursa Prison; cited as V-Ns]

Letters to Memet Fuat; cited as LMF

The poet himself senses the necessity of his own verse, and his contemporaries feel that the poets destiny is no accident. Is there any one of us who doesnt share the impression that the poets volumes are a kind of scenario in which he plays out the story of his life? The poet is the principal character, and subordinate parts are also included; but the performers for these later roles are recruited as the action develops and to the extent that the plot requires them. The plot has been laid out ahead of time right down to the details of the denouement.

ROMAN JAKOBSON

NZIM HIKMET IS A MASTER POET of the Turkish language, and my book recounts the fatedand fatefulscenario that he scripted in his poems and played out in his life, as his life and work came to chart each others course. The principal character of both stories goes by Nzim in Turkey, the given name that may have helped pre-script his destiny. In Turkish, Nzim means a poet, one who orders and arranges, a maker of verse; his very name predicates his mythopoetic stature. For Nzim is a larger-than-life figure who comes to us swathed in legendsboth the legible inscriptions of his work and many, many stories that may or may not be true stories. His poems chronicle his mythogenesis, and scores of memoirs and biographies written by those who knew him aid and abet his construction of a myth. Here it is difficult to tell fact from fiction. While all myths have different versions and many variants, in the construction of recent mythologies the various personal and political motives that are always in play are all the more apparent.

The difficulty in Nzims casea myth in his own timecompounds the generic problem of writing the biography of any poet, where one leaves somewhat more secure disciplinary grounds and enters a hazardous minefield, a no mans land of one mans life. A literary biography is not quite historical writing, but it must be faithful to the facts, insofar as they can be determined, and establish historical contexts. Nor is it quite fiction; yet, although it must not speculate, it must create a narrative to establish connections and impart a fictional arrangement, an order, to a life. It is not quite literary criticism, either, yet it must engage the texts as formal creations that account for the biographers interest in her project in the first place.

Next page