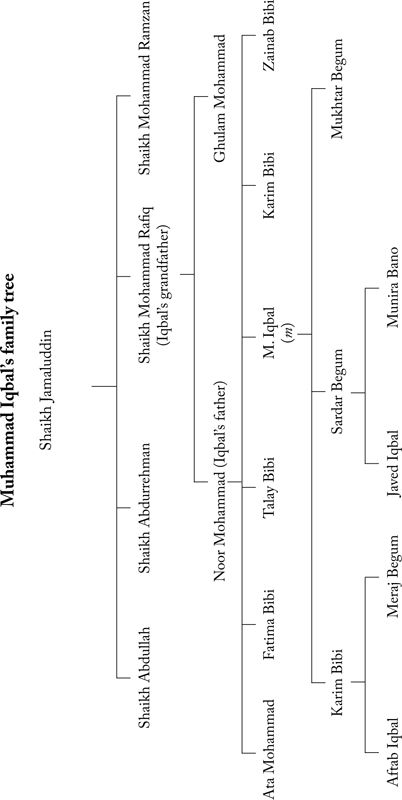

The author and publishers would like to thank Dr Muhammad Suheyl Umar, director, Iqbal Academy Pakistan, Lahore, for his kind permission to reproduce these illustrations in this work.

PROLOGUE

Why Iqbal?

One evening in April this year I was sitting with a friend in Blue Jazz Caf in Singapores Arab Street neighbourhood. My friend, who is a professor in a prestigious university in Delhi, asked me what I was currently working on. Iqbal, I told him, a biography of Allama Muhammad Iqbal.

But why a biography of Iqbal? He pressed me with a perfectly valid question. What is your connection with Iqbal?

He had a point. It is true that I have no direct connection with Iqbal. The great poet was dead long before I was born. Im not from Pakistan or the Punjab. I have never been across the border, not even to research this book (a variety of things prevented this). I am not even an Urdu scholar, though I was enrolled for a masters degree in Urdu at Delhis Jawaharlal Nehru University. I was forced to drop out after a year due to insufficient attendance (my loyalties were divided: I was pursuing a course in journalism at the same time).

My friend and I talked for a long time about Iqbal, Urdu, Partition, and about how the idea that a state could be created on the basis of religion was a failed idea. If the idea of Pakistan as a land for Indian Muslims was such a good idea, then how come Bangladesh came to be separated from Pakistan, he argued. If Iqbal stood for the idea of Muslim nationalism, and not territorial nationalism, then it was already a failed idea, he railed on.

Later on, I thought at length about my friends question: What is my connection with Iqbal? I believe that my bond with Iqbal and his poetry is deeper than that of just a lay reader and plain admirer of his scintillating and soul-stirring verses. I am attached to Iqbal by an umbilical cord that is both spiritual and intellectual.

The bond is not without its physical manifestations too. I grewup in a small town in Bihar and the school that I attended until my matriculationInsan Schoolwas founded by Dr Syed Hasan, a disciple of Dr Zakir Hussain, independent Indias first Muslim President. Dr Hasan, who had a successful academic career in the USA, left everything behind to found a school in one of Bihars most backward districtsKishanganj, my hometown. And one of his inspirations was Iqbal whom he had met as a student.

My first tutor, Mahboob Alam Sahebwho has dedicated his life to the Urdu language as a teacher in a small village in West Bengalwas very fond of Ghalibs and Iqbals poetry. From when I was young, he exposed me and my sister Soghra to Iqbals inspiring verses. Famous lines from his poetry such as Khudi ko kar buland itna ke har taqdeer se pehle... and Tu Shaheen hai basera kar pahadon ki chattanoon me became part of our daily speech. Slowly, Iqbal seeped into us during languid summer afternoons and hurried winter evenings, while we did our school work.

When I came to Aligarh to attend university, I stayed in Allama Iqbal Hall as a boarder for five years. I also became one of the editors and contributors to the halls magazine, Iqbal. The great poet, in an oblique way, became a real presence in my life.

Years later, when I trooped over to study at J.N.U. in Delhi, I was horrified to realize that Iqbal had been slowly erased from our memories. In Aligarh, his poetry was alive and his presence could be felt. This was not so in Delhi. I began to wonder how many people in India, both Hindus and Muslims, especially of the younger generation, knew about Iqbal today? Some might know him as a poet, but how many know that there is much more to Iqbal than his poetry. Neither his contribution to the philosophy of Islam nor his achievements as a politician are common knowledge. How many know about Iqbals political role in the creation of Pakistan and why a patriotic poet like him came up with the idea of Pakistan?

The story you are going to read in these pages is an attempt to narrate Iqbals life once again for those who have forgotten him. I dont claim it to be a comprehensive account, for to write such a book would require a lot of time and research, and in the time that I was given, I have tried my best.

I hope this book will satisfy those curious about Iqbal and spur them onto further reading. This humble effort is my spiritual homage to Iqbal and his universal message.

Zafar Anjum

Singapore

July 9, 2014

Introduction

Come dear friend! Thou hast known me only as an abstract thinker and dreamer of high ideals. See me in my home playing with the children and giving them rides turn by turn as if I were a wooden horse! Ah! See me in the family circle lying in the feet of my grey-haired mother the touch of whose rejuvenating hand bids the tide of time flow backward, and gives me once more the school-boy feeling in spite of all the Kants and Hegels in my head! Here Thou will know me as a human being.

Iqbal, Stray Reflections

Allama Muhammad Iqbal, one of Indias first patriotic poets, whom Sarojini Naidu called the Poet laureate of Asia, remains a controversial figure in the history of the Indian subcontinent. On the one hand, he is seen as a Pan-Islamic philosopher and the Spiritual Father of Pakistan, and even the inspiration of the Iranian Revolution. On the other, his patriotic and socialistic poems, and his intellectual struggle against both the colonial powers and Islamic fundamentalists places him in the ranks of the twentieth centurys major political thinkers.

Professor Yahya Michot, fellow of Islamic Studies at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies and the Faculty of Theology, Oxford University, regards Iqbal as the last great Muslim thinker in the lineage of Ghazali, Razi, and Shah Waliullah. Many scholars have also highlighted Iqbals fondness for his homeland (pre-Partition India), and pointed out how he used Sanskrit vocabulary and figures of narrative from Hindu folklore and mythology in his poetry.