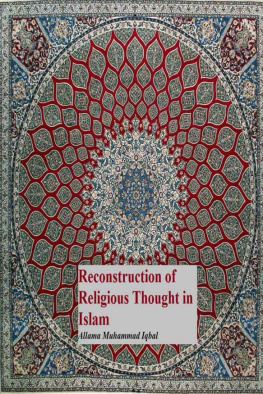

, recited to this day as an alternate anthem. A pre-eminent poet of India in the early twentieth century, he eulogized the land and its peoples with his mellifluous verse. He published several collections, including

(1935). In his later years he became the voice of Islam in India, advocating its causes through his writings, particularly

(1930), his poetry and public speeches. In Pakistan today, he is regarded and cherished as a founding father.

Poet, translator and columnist Mustansir Dalvi teaches architecture in Mumbai.

Introduction

Hai ajab majmooa-e-izdaad, Ai Iqbal tuRaunaq-e-hangaama-e-mehfil bhi hai, tanhaa bhi hai O Iqbal, you really are something else! You can be the life of the party, yet be alone all the while.

Aashiq-e-Harjaai (The Philanderer)

I

It is a hundred years since Muhammad Iqbal first recited

Shikwa (Taking Issue) at a gathering of the Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam in Lahore in 1909. Through the tumultuous century that succeeded this event, the poem and its response,

Jawaab-e-Shikwa (Allahs Answer, 1913), have assumed a strange afterlife in the subcontinent.

Although his poetry is appreciated on both sides of the border, in India and in Pakistan, Iqbal is viewed through different lenses. In Pakistan, Iqbal is immortalized as a founding father. In veneration, his titles precede his name. Iqbals legacy is more interesting in India. His poem of 1904, Taraanaa-e-Hindi (Song of India), is an anthem to this day. His early poems still inspire patriotic nationalism and communal amity.

However, his subsequent inclination beyond Indian nationhood to a pan-Islamic global identification has been seen as problematic for its divisiveness. Shikwa marks the shift that reaffirms Iqbals Muslim identity and asserts his affiliation to the ummat, or the Islamic community of the world, and for that very reason remains a deeply conflicted text that emphasizes a fraternity through difference. Ever since their first unveiling, Shikwa and Jawaab have been appropriated to forward various agendas through recitation, repetition and selective quotation. Those who claim Iqbal as their own, both in India and in Pakistan, have found different ways of defining their contemporary relevance.

II

For Indians today, Iqbal is best known as the composer of

Saare jahaan se acchha (from

Taraanaa-e-Hindi), which

Ho mere dum se yunhi mere watan ki zeenatJis tarah phool se hoti hai chaman ke zeenat Let me bring glory to my land with every breath, like blossoms that are the glory of the meadow. Being Indian, and of India, inspired several of Iqbals poems.

He wrote of the land and its geography in poems like Himalaya and Taraanaa-e-Hindi; its great seers and deities in Nanak and Ram (whom he called Imam-e-Hind, or Prophet of India); and its poets in Mirza Ghalib and Dagh. Iqbal even translated the Gayatri mantra from the Sanskrit into Urdu verse as Aaftaab (The Sun). In Nayaa Shivala (New Temple), Iqbal deifies his homeland. Using a vocabulary more Hindi than Persian, his views are syncretic of Hindu and Muslim thought: Patthar ki mooraton mein samjha hai tu Khudaa haiKhaak-e-watan ka mujhko har zarra devataa hai You assume God exists only in icons of stone, every speck of earth that is my land is Divinity itself. His poems found easy acceptability with their images of reconciliation and mutual respect. National leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore praised his verse.

Then, in 1905, Iqbal left for Europe for a three-year sojourn. Between 1905 and 1908, Iqbal travelled extensively and studied philosophy, law and metaphysics in different parts of Europe. His years outside India brought about a profound change in his perception of territorial nationalism. He was closer to the world-changing events of his time; he observed the rising influence of Western materialism and the corrosion of Islamic power bases. He visited the former sites of Islamic dominance in Europe and felt a great nostalgia for this loss. Iqbals writings changed: his gaze stretched beyond nationhood to a larger universe of the fraternal Islam of the ummat and the millat (the community of the faithful).

This internationalism was quite removed from the earlier intensity, fervour and patriotism of being an Indian. Iqbal now assumed the mantle of an alienated Muslim for whom, in the words of Mohammed Upon returning to India, Iqbal wrote Shikwa and, later, Jawaab-e-Shikwa. In the rift between Iqbals years as a poet of India and his later Islamist leanings, lie these poems. For Indians, then, Iqbal is a poet with a past.

III

In Pakistan,

Shikwa is the avant-garde to a brave new world of Muslim self-determination. It is a blueprint on which the future statenot even articulated when these poems were written could base both its actions and abstractions.

Muhammad Iqbal himself is invoked variously, the most common being the appellation of Allama, or scholar. He is also Sir Muhammad Iqbalhe received a knighthood from the British government in 1922 in recognition of his poetry. He is Shayar-e-Mashriq (Poet of the Orient), Hakeem-ul-Ummat (Doctor of the Community) and Mufakhir-e-Pakistan, or Philosopher of Pakistan, on the basis of his writings and speeches from 1909 onward until his death in 1938. Iqbal is regarded as a pillar of the new state of Pakistan that came into being in 1947. His life and work have been analysed and scrutinized constantly by literary critics and religious ideologues alike, in print, in talk shows, on Internet forums and on blogs, where determined attempts are made to cull certainties and universalities from his writings. Shikwa and Jawaab are no longer mere poems but manifestos, and the abstractions inherent in his poetic turn of phrase are heightened to the point of dogma.

For Pakistan, Muhammad Iqbal is the voice of the futurehis poems its harbinger: Astr-e-nau raat hai, dhundlaa sa sitaaraa tu hai Tomorrow is still in darkness, and you are the faint new star. Jawaab-e-Shikwa It would be worthwhile, then, to place these poems in the context in which they were written, and be conscious not to attribute meanings in the light of later events. I have kept this in mind as the guiding spirit of this translation.

IV

What are fundamentally paeans of alienation have been aestheticized through the years, through incanted recitation, or

tarannum, which shifts the emphasis from the content to the musicality of the words and the rhyme. The politics that drive the

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS