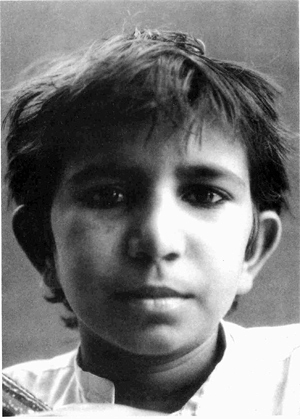

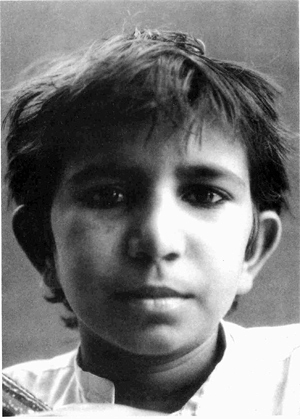

Courtesy of Richard Sobel/Reebok Human Rights Foundation

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For all the children still waiting to become free, and for my parents

A Note From the Author

A few years ago, the Reebok Human Rights Foundation invited me to Boston to meet an extraordinary young boy by the name of Iqbal Masih. At that time I was in the middle of a series of intense interviews with human rights activists who were visiting New York. I thought to myself, Iqbal is so young and so committed to his cause that there will be plenty of opportunities to talk with him in the future. How wrong can one writer be!

After Iqbals tragic death, two of his friends and fellow Reebok award winners, Li Lu of China and David Moya of Cuba, asked me to write about Iqbal. The result is this book.

A great deal has been written about Iqbal, child bondage, and the Bonded Labor Liberation Front. Unfortunately, much of the information is inconclusive at best and incorrect at worst. It was perplexing to sort out truth from fiction in the paradoxical life of Iqbal Masih. To this day, there is some question about Iqbals true age.

To research this book, I spoke with people who either knew Iqbal or met his family. They include Ron Adams, Doug Cahn, Sharon Cohen, Arvind Ganesan, Farhad Karim, Mark Schapiro, and Paula Van Gelder. I also reviewed materials from highly respected human rights organizations. Anti-Slavery International, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, Human Rights Watch/Asia, the National Child Labor Committee, and UNICEF provided me with materials about contemporary forms of slavery and the history and background of many of the grassroots organizations that are active in this field.

Iqbal was widely quoted in newspapers, magazines, and videos. More often than not, he repeated the same answers to reporters questions. Because he worked with many different translators, his descriptions and quotations were slightly different from one source to another. Trudie Styler interviewed Iqbal for the February 1996 issue of Harpers Bazaar magazine. It was a wonderful, touching interview called The Short, Tragic Life of Iqbal Masih. When in doubt, I used Iqbals quotes from Stylers article.

Two other magazine articles, Child Labor in Pakistan, by Jonathan Silvers for the Atlantic Monthly magazine, February 1996, and Children of a Lesser God, by Mark Schapiro for Harpers Bazaar, April 1996, gave me invaluable material and insight into this complex topic. They are both worth reading if you want to learn more about child bondage.

I am grateful to all the journalists, researchers, and human rights activists who helped me write this book. My sincere appreciation to my expert readers: Jeannine Guthrie, Farhad Karim, Shalini Dewan, and Ron Adams. Although writing is ultimately a solitary affair, there were a number of friends and colleagues who contributed to this book: Gay Young, my agent; Ian Graham and the wonderful staff at Henry Holt; Sharon Cohen; Paula Van Gelder; and Doug Cahn at the Reebok Human Rights Foundation. My husband, Bailey, provided inspiration, wise counsel, and encouragement. Most especially, I want to thank my editor, Marc Aronson, who supported me through every step and stumble. Together we tried to tell the story of bonded children and to celebrate the life of Iqbal Masih.

I wish with all my heart that this book was not necessary. I wish I had Iqbal here beside me, guiding me through the ins and outs of a now happy life. Even more, I wish that the horrible plight of child bondage no longer existed and that this book would be read as history, not as current events.

Prologue

I am one of those millions of children who are suffering in Pakistan because of bonded labor and child labor. But I am lucky. Due to the efforts of the Bonded Labor Liberation Front (BLLF), I am free and I am standing in front of you here today. After I was freed, I joined the BLLF school. I am studying in that school now. For us slave children, Eshan Ullah Khan and BLLF has done the same work that Abraham Lincoln did for the slaves in America. Today you are free and I am free, too.

Unfortunately, the owner of the business where I worked told us that it is America who asks us to enslave the children. American people like the cheap carpets, the rugs, and the towels that we make. So they want bonded labor to go on. I appeal to you that you stop people from using children as bonded laborers because the children need to use a pen rather than the instruments of child labor.

Children work with this instrument. [Iqbal holds up a carpet tool.] If there is something wrong, the children get beaten with it. And if they are hurt, they are not taken to the doctors. Children do not need these instruments but they need this instrument, the pen, like the American children have. [He holds up a pen.] Unfortunately, many children do not use pens right now. I hope that you will help BLLF, just as they have helped us. By your cooperation BLLF can help a lot of children and give them this instrument, the pen.

I share what I remember: how I was abused and how other children are being abused there, including those that are insulted, and are hung upside down, and are mistreated. I still remember those days.

I saw Pakistani-made rugs in American stores, and I was very saddened knowing that they were made by bonded labor children. I felt very sorry about it. I request President Clinton to put sanctions on those countries which use child labor. Do not extend help to those countries still using children as bonded laborers. Allow the children to have the pen.

And with this I gratefully and thankfully acknowledge Reeboks contribution in that direction. They have called me for this prize, and Im very grateful to them. Thank you.

We have a slogan at school when children are freed. We all together say we are free. And I request you to join me today in raising that slogan here. I will say, We are, and you will say, Free.

I QBAL M ASIH , 1994

The slight young boy from the other side of the world raised both his arms triumphantly. WE ARE, he shouted. His cry, both fragile and powerful, energized two thousand voices.

FREE, the voices screamed. FREE! FREE! FREE!

In response to the audiences chant, his impish smile lit up the stage. Pakistani-born Iqbal Masih was addressing an audience at Northeastern University, in Boston. He was in America to receive the Reebok Human Rights Youth in Action Award. Just the fact that he was there, standing before the crowd, was a stunning accomplishment.

Iqbal accepting Reeboks Youth in Action Award

Courtesy of Richard Sobel/Reebok Human Rights Foundation

At one time, Iqbal Masih was destined to spend his entire life tucked away in a tiny factory, weaving carpets. Instead he emerged to become an international speaker and award winner.

Iqbal Masih was one of the millions of children all over the world who fill their days working to help their impoverished families pay off debts or eke out a small living. Most indentured children work at home, on farms, or in dangerous jobs such as street hawking, brick breaking, and ragpicking. Some children weave carpets. Others sew clothing and solder jewelry. Some make toys and sporting equipment. Others grind metal surgical tools, such as syringes. These and other products are then exported abroad, especially to Europe and the United States. Not all exported goods are made by the sweat and exploitation of children. UNICEF reports that only a small amount of exported goods, about 5 percent, are made by working young people.