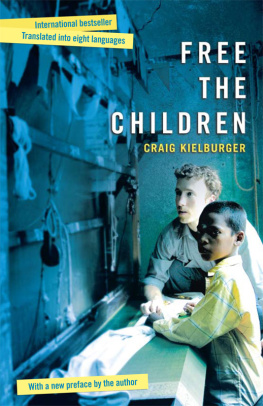

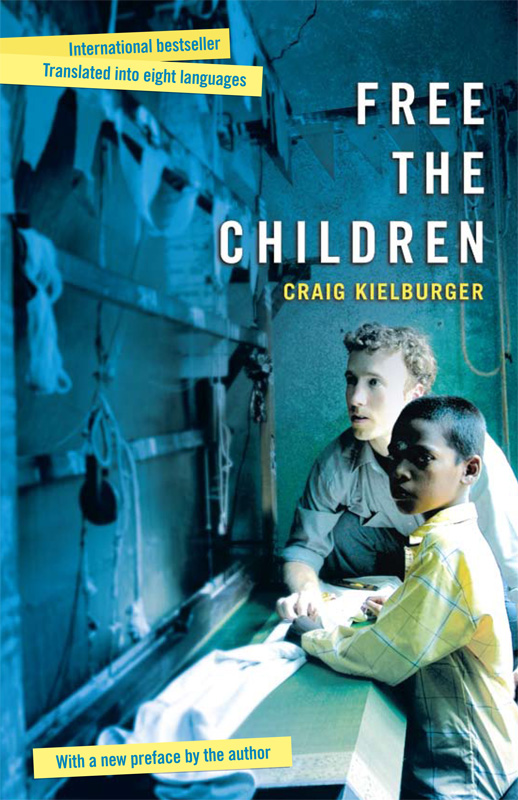

FREE

THE

CHILDREN

CRAIG KIELBURGER

FREE

THE

CHILDREN

CRAIG KIELBURGER

Me to We Books

233 Carlton Street

Toronto, ON M5A 2L2 Canada

www.metowe.com/books

Free the Children

Copyright 2010 by Craig Kielburger

10 11 12 13 5 4 3

All rights reserved.

No part of this work covered by the copyright

herein shall be reproduced or used in any

form or by any meansgraphic, electronic, or

mechanical without the prior written permission

of the publisher. Any request for photocopying,

recording, taping, or information storage and

retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be

directed in writing to The Canadian Copyright

Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an

Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopy-right.ca

or call toll-free 1.800.893.5777.

ISBN 978-0-9784375-0-3

Originally published in 1998 by HarperCollins.

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens.

Printed on post-consumer waste recycled paper.

CONTENTS

I t has now been more than a decade since I first learned about the life and death of child rights activist Iqbal Masih and embarked on a journey that would forever change my life. It all started with one bold headline: Battled child labor, boy, 12, murdered. As a Grade 7 student from a middle class suburban neighbourhood, I was shocked to discover these words glaring back at me from the front page of the newspaper one morning. This, my first encounter with injustice as experienced by a child like myself, dramatically changed my ideas about the world. More importantly, it made me realize the world had to change.

In the beginning, Free The Children was little more than a small group of classmates eager to raise awareness about child labour. None of us had much experience with social justice workjust a desire to take action. Having discovered that children around the world were being forced to work in terrible conditions, toiling away day after day without the hope of going to school, we became determined to work toward change. While striving to free children from poverty and exploitation, we also sought to free our peersand ourselvesfrom the idea that we were too young to make a meaningful difference in the world.

At the time, youth activism had yet to come into its own. A more broadly inclusive approach to childrens issues had yet to appear on the agenda, let alone become a priority. Childrens interests were almost always represented by adults, and young peoples voices were rarely acknowledged. In those days, the idea of children helping children was practically unheard of. As children speaking out on childrens rights, we were an oddity. While our families and friends were always there to cheer us on, others were generally skeptical about what we could accomplish. In the early days, few decision-makers were willing to listen to what we had to say, and fewer still were supportive. With adults unwilling to get involved, we began to make connections with the one group of people we knew would understand: other young people.

Excited at the prospect of making a difference in the world, children and youth flocked to our organization. With this influx of energy and creativity, Free The Children was able to expand the scope of its activities. Soon, we were speaking to groups across the country, and people were beginning to listen. All our hard work began to pay off as more and more people started to pledge their support.

It was around this time that I first got the idea of travelling to the developing world. I knew that if we were to help child labourers, we needed to learn from the children themselves. Of course, I didnt yet have any idea how to arrange a trip like this, let alone convince my parents to let me travel halfway across the globe. I just knew that this was something I had to do.

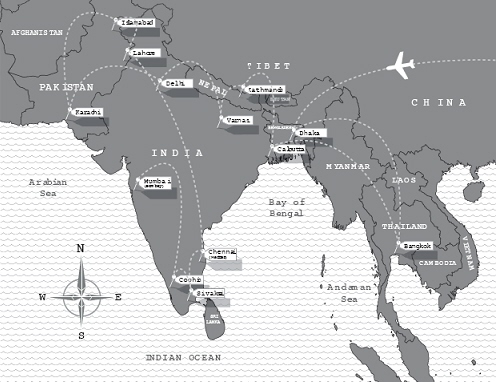

My trip to South Asia was to mark a significant turning point in my role as a childrens rights activist, as this account of my adventures makes clear. During my journey through Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Nepal and Pakistan, I had the chance to witness childrens challenges first-hand. I had left home expecting child labour to be something secret and hidden, but to my surprise nothing could have been further from the truth. Working children were everywhere, and eager to talk to me about their experiences. Kids nearly half my age told me that they had no choice except to work. Time and time again they explained how hard they struggled, hoping for a better future. I was in awe of their courage. Often, I felt frustrated by how little I could actually do to help my new friends. Slowly, I came to realize that the one way I, a twelve-year-old from Canada, could really make a difference was by sharing their stories. I could return their friendship by making certain they would never be forgotten.

While travelling in South Asia I came to understand that child labour is both a cause and consequence of poverty. I began to see that it wasnt enough to simply be against child labour when children and their families were desperately in need of basic necessities and new opportunities. It was then that I first came to understand that freeing children means more than ensuring that no child be enslaved: it means empowering young people and their families. By the end of my trip, it had become clear that Free The Children had a lot of work to do.

In the early 1990s, the World Summit for Children and the Declaration on the Rights of the Child had promised to usher in a new era in the protection and promotion of childrens rights. Over the course of the decade, child labour made its way onto the international agenda, and the world became willing to address a number of issues that had for years been swept under the rug. By the time Free the Children was first published in 1998, our organization had become much larger than any of us would have imagined. Youth in Action Groups had begun to spring up all over the world. We had plunged into development work, building schools and establishing alternative income programs in a number of countries in the developing world. Young people were becoming more and more aware of their power, and were beginning to use it to help their peers around the world.

It was an exciting time filled with many important firsts, both for our organization and children everywhere. Free The Children India organized a rally to protest the kidnapping of handicapped children in West Bengal who were being forced to work as beggars and drug runners to Persian Gulf countries. As a result, the Indian government promised to put a stop to this practice. Fourteen-year-old Daniel Strand and the young people of Free The Children Brazil helped to convince the Brazilian government to invest more than one million dollars in projects to alleviate child labour in Salvador de Bahia. Of course, in other cases it was clear that promises to the worlds children were easier made than kept. We learned a lot during those years, and Free The Children continued to expand the scope of its activities. At the time, however, even we could not have imagined how our organization would evolve.

Over the past twelve years Free The Children has grown into the worlds largest network of children helping children through education. Whereas we used to work out of my parents garage, our Toronto office now occupies an entire building on the citys east side. My older brother Marcnow a Harvard graduate, Rhodes Scholar and Oxford-educated lawyeracts as a mentor to all of us at Free The Children in his role as chief executive officer. While we still depend on the efforts of our dedicated volunteers, we now work with a team of full-time staff who strive to empower young people everywhere to create positive social change.

Next page