For the children of Aotearoa New Zealand

For every survivor of child sexual abuse finding their way over the hurdles

And for those who love them and travel that journey with them

Contents

Foreword

I was so brutalised inside, and then I had to live with that shame.

Survivor of child sexual abuse

WE NEW ZEALANDERS ARE A compassionate and generous people. We want nothing but the best for our young people. Our vision for childhood is one where its taonga our children are nourished and nurtured, and where they thrive. But child abuse, and in particular child sexual abuse, casts a sharp shadow across this vision. Increasingly we are aware of the power of this shadow and the price it demands from too many of our children. That cost is physical, emotional, psychological, indeed spiritual. It can leave children diminished and broken. The tragic fact is that New Zealand has had, and continues to have, a major problem with child sexual abuse. It is a crisis. No instance of abuse of a child is acceptable, but the rate of child sexual abuse in this country is profoundly concerning.

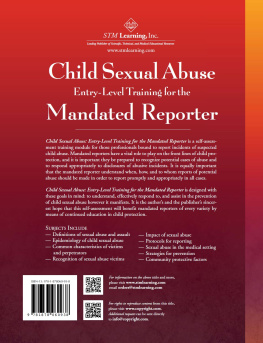

Participants in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Study of 1037 children were asked to report if they had experienced any kind of unwanted sexual activities that involved physical contact before the age of 16. The study indicated that 30 per cent of female and 9 per cent of male participants had experienced some form of sexual abuse. That is a shocking statistic. And given the inhibitions that discourage reporting, it is likely the actual level may be higher still.

The level of concern about this issue within New Zealand has been evidenced by the insistent demand for a Royal Commission into historical abuse of children in state care, and the further call to ensure the inquiry be extended to include faith-based institutions.

The original terms of reference proposed that the Royal Commission consider complaints up until the end of 1999. This implied the nave assumption that abuse, including sexual abuse, is somehow a thing of the past. But this is little more than a convenient myth enabling us to shelve our concern about child sexual abuse.

The Safety of Children in Care statistics, released by Oranga Tamariki Ministry for Children in March 2019, give the lie to that myth. Not only do they demonstrate that the sexual abuse of children is still happening, they also further identify that children in the care of the state are experiencing a 10 per cent rate of repeat abuse in general.

All this points to the timeliness of Free to Be Children: Preventing child sexual abuse in Aotearoa New Zealand. This book draws together significant contributions by writers and researchers from wide-ranging fields of expertise. Together they explore the nature of the problem and exhibit the value of a knowledgeable, informed, expert response.

Free to Be Children also draws our attention to aspects of the issue that may be new to many: the reality of child sex trafficking in Aotearoa; the challenge of keeping children safe in the digital age; restorative justice for child victims and survivors.

The Office of the Childrens Commissioner is committed to prioritising the best interests of children, as this book does. We also actively commit to consulting with children, to make their views known and to give them weight. Historically, as a country, we have done that remarkably badly. Government departments, ministries, local government and community groups have too readily privileged adult voices in decision-making.

Fortunately, things are changing. Our legislation makes taking account of childrens voices essential. The Childrens Commissioner Act 2003 gives the commissioner a mandate to seek out childrens voices, to listen to them, and to give them serious consideration (sections 13 and 14). These sections of the Act provide the basis for how we discharge our specific statutory obligations to investigate, monitor, assess and help the work of Oranga Tamariki (section 14). Our determination to prioritise the voices of children has led us to revolutionise our approach to monitoring work.

The voices of children and young people change the discussion. They rebalance emphases. They draw attention to assumptions that no longer hold. The recent student climate change strikes, demanding that attention be focused on the global climate change crisis, provide an excellent example. The distinctive value childrens voices add to our krero is a field that would benefit from further research and exploration. This is true also in respect of childrens experience of abuse.

Free to Be Children makes an excellent and contemporary contribution to the discussion of child sexual abuse. It will provoke thought on this crisis. It will broaden readers understanding of the key issues at play. It will contribute to a better response and encourage a more professional and effective practice across all disciplines. It should be required reading for anyone working in the field, and it will richly repay careful reading.

Judge Andrew Becroft

Childrens Commissioner

Preface

WHEN I HEAR PEOPLE SAY children are so resilient, my experiences with adult survivors of child sexual abuse always make me wonder where on earth they are coming from. Raising children is very hard work and sometimes anxiety-provoking. In talking about the sexual abuse of children the last thing I want to do is stir more anxiety. However, if a society wants to address the problem of child sexual abuse it must face the fact that children are vulnerable. Children are not sexual beings for the gratification of others, but in New Zealand too many abusers think they are. Its time for us as a country to open our eyes to the extent of this problem. We need to strengthen our resolve to address it, to get well informed and to take effective steps forward.

The unhealed psychological-trauma wounds of child sexual abuse are hugely costly: for the child, for the adult they grow up to be, for all those who love them and for our society as a whole. Emotionally or physically, survivors of abuse are called on at some point in their lifetimes to do the work of facing and working through their pain. Some do that, some do not; and while its certainly achievable, it also takes great courage and persistence. Even when very thoroughly addressed, many survivors find that significant scars remain.

If life has brought children traumatic experiences which they havent had good support to work their way through, some will develop overtly destructive behaviours of many kinds. Others may appear fine they have learned to repress, deny or otherwise hide their wounds. I dont want to detract from the value of resilience; rather, I want to shine a spotlight on it. I celebrate all the coping mechanisms every sexually abused child has ever used to help themselves survive. I also know that many coping mechanisms operate at a cost, and that they have a use-by date.

Why have I edited this book? I aim, first, to bring light to this issue, then to go beneath the surface and combat taboos on talking about child sexual abuse. I want this book to be a voice for those who cant speak out or who would be at increased risk if they did. I want it to challenge the invisibility of abused children and the power of abusive adolescents and adults. Thats why its authors name what happens and speak truths that some people may not want to know about.

Next page