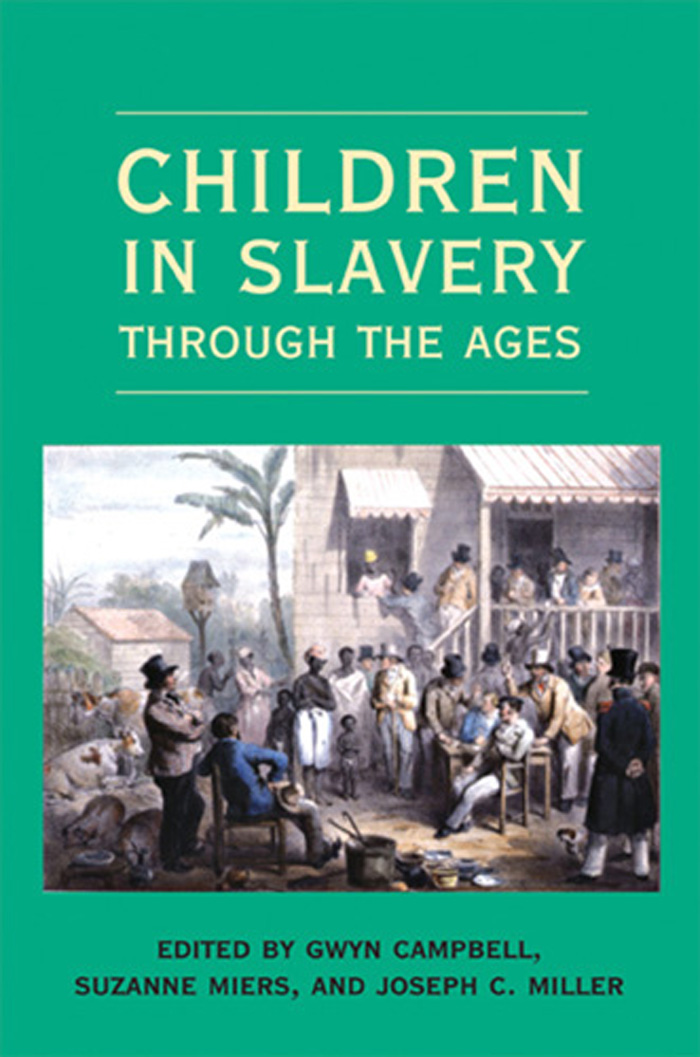

CHILDREN IN SLAVERY THROUGH THE AGES

CHILDREN IN SLAVERY THROUGH THE AGES

Edited by

Gwyn Campbell

Suzanne Miers

Joseph C. Miller

OHIO UNIVERSITY PRESS

ATHENS

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohioswallow.com

2009 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Children in slavery through the ages / edited by Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Miers, Joseph C. Miller.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8214-1876-5 (hbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8214-1877-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Child slavesHistory. 2. SlaveryHistory. I. Campbell, Gwyn, 1952II. Miers, Suzanne. III. Miller, Joseph Calder.

HT861.C45 2009

306.3'6208309dc22

2009023495

CONTENTS

EDITORS INTRODUCTION

OUR AIMS

This is the first of two volumes on children in slaverya subject that has only recently become the focus of academic research. Scholarly attention has up to now centered primarily on adult male slaves, first in the Americas and the Caribbean, then in Africa, and more recently on women in slavery. Throughout the known history of slavery, children were in a minority. However, as the chapters in these volumes show, at least for the transatlantic, Indian Ocean, and internal U.S. trades, they were increasing in numbers and importance from the late eighteenth century as slavery in its classic form came increasingly under attack. Moreover, it is possible that children currently constitute a large proportion of the victims of the various forms of modern slavery. Our aim here is to provide comparative examples of child slavery, from the eighth to the twentieth centuries. Child slavery is surely the most pitiful form of slavery, since children are the most malleable of slaves and have the least powers of resistance. Most slave children, however, have a high degree of adaptability, which, as will be seen, was and is central to survival in a world in which they were, and still are, valued and thought of as trade goods, possessions, and generators of wealth, rather than as human beings with needs of their own.

We have space in these two volumes for only a few examples of the role and fate of child slaves. Whole regions, and whole sections of the economy in which children were, and still are, enslaved, remain to be explored. This is a pioneer work and we hope that other scholars will follow us in the search for information on this little-known subject.

OUR SOURCES

Apart from the uses to which children were put, how they were affected by their slave experiences has been little researched, and our sources are often sketchy. Children did not keep diaries or other records of their lives and treatment while in bondage. Adult slaves, particularly freed slaves, recorded facts about their childhood, but their reminiscences, albeit highly valuable, are filtered through later experiences. However, there is some firsthand information on those children who were freed from captured slave ships or slave caravans and handed over by the British to missionaries in Sierra Leone, East Africa, and India after the trade became illegal, during the nineteenth century. There are also the accounts of those who, at the same time, sought refuge with the European colonial authorities, particularly if, as in Mauritius, a protector of slaves had been appointed. More recently, there are the stories of children who fled to British consulates in Arabia, or to British officials in the Persian Gulf states, where slavery was legal until the 1960s. The last country to outlaw slavery was Oman, in 1970. Unfortunately, the full accounts of these childrens experiences in Arabia were either unrecorded or not sent back to the Foreign Office by British officials. However, future research on the ground will surely yield much valuable information.

Slavery took many forms, some crueler than others. On the one hand, unknown numbers of children in many lands have, over the centuries, been torn from, or even sold by, their natal families, taken far from home, often resoldsometimes many timesand raised among strangers. They were often overworked, poorly fed and housed, and exposed to sexual abuse, cruelty, disease, and other dangers. Their welfare has always been subordinated to the interestseconomic, political, or socialof their owners. Child slaves were, and sadly still are, the defenseless victims of poverty, wars, raids, and trickery, as well as greed and a thirst for power. However, as the following chapters show, this picture of brutality and suffering must be modified by the fact that for some children life in slavery was preferable to a life of poverty at home. Moreover, some boy slaves were trained to wield power and some girl slaves ended up leading lives of luxury. Sadly, they represented a small minority of the children in bondage.

DEFINITION OF SLAVERY

A number of the contributions to this volume underscore one of the major problems in comparative slavery studies: the definition of slavery. In the conventional historiography that has focused on European forms of bondage, a reasonably clear consensus has arisen as to the meaning of the term. This consensus is assisted by the common linguistic origin of the term slave in most European languages. A slave is generally taken to constitute a chattel, deprived of civic rights, and whose status is inherited by his or her children. Further definitions have concentrated on the social death and the ubiquity of violence in the slave experience. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that there existed, notably in the non-Atlantic world, many different forms of bondage, which changed according to time and place and which often overlapped with one another. These systems, some of which are examined in this volume, at times approximated to the Atlantic

THE DEFINITION OF A CHILD

Our first task here is to define what we mean by a child. Today, the United Nations and many Western countries define a child as anyone under the age of eighteen. However, this is not a universal yardstick. For instance, the age of consent to marriage for girls in some countries is as low as twelve. The legal age at which children of either sex enter the work force, are conscripted for military service, are allowed to marry, vote, or drive varies from country to country. The legal school leaving age could be an indicator of legal adulthood, but in many countries education is not compulsory, and in some countries few if any girls attend school. Many children do not have birth certificates and their age is not officially known.

The difficulty of defining childhood is even greater when discussing the past. In part this stems from the paucity of records. However, it also derives from concepts of childhood often radically different from modern Western concepts. Even in Enlightenment Europe, which stressed the capacity to reason as the test of the civilized human being, children, alongside females and nonwhite males, were considered irrational and animal-like and thus debarred from civic rights and responsibilities. Children required domestication, and slavery, it was often argued, was the protected status best suited to that end for nonwhite children. The definition of a slave child was frequently determined by widely varying criteria, including appearance and height. A vivid example of how difficult it can be to judge a childs age by his or her appearance is provided by George Michael La Rues chapter in this volume.