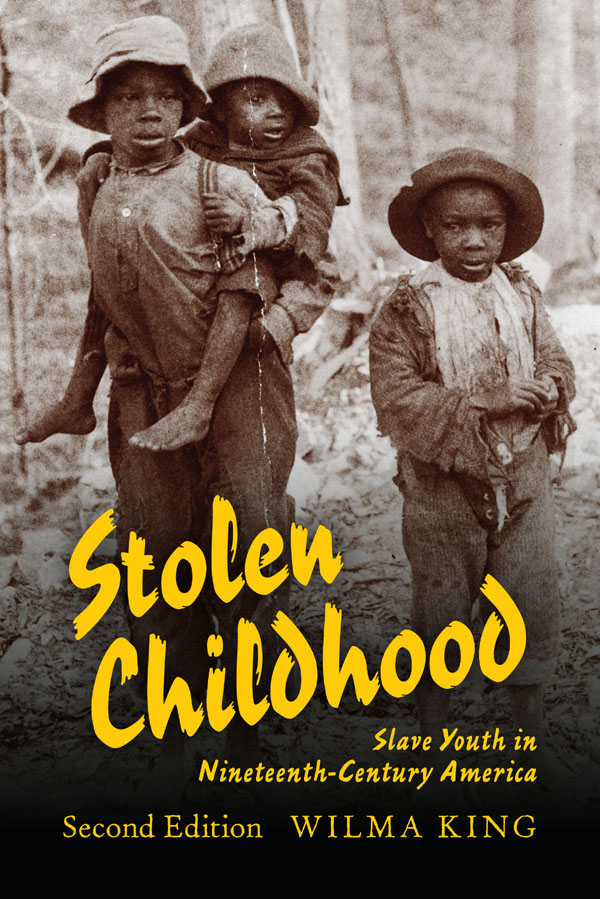

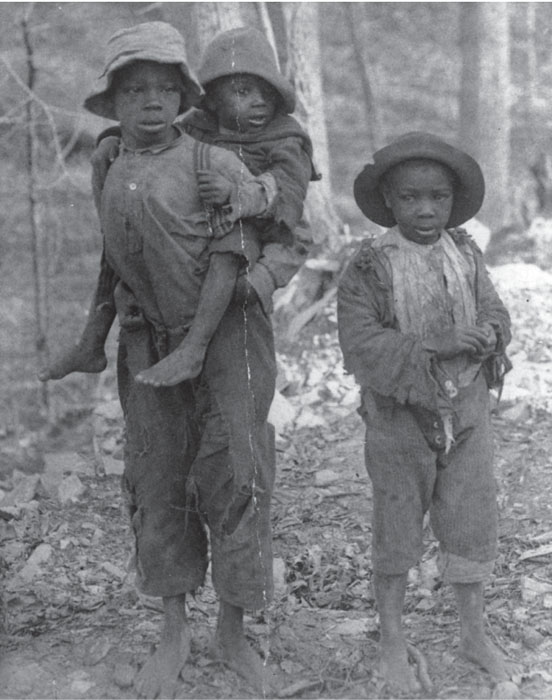

Stolen

Childhood

BLACKS IN THE DIASPORA

FOUNDING EDITORS

Darlene Clark Hine

John McCluskey, Jr.

David Barry Gaspar

EDITORIAL BOARD

Herman L. Bennett

Kim D. Butler

Judith A. Byfield

Leslie A. Schwalm

Tracy Sharpley-Whiting

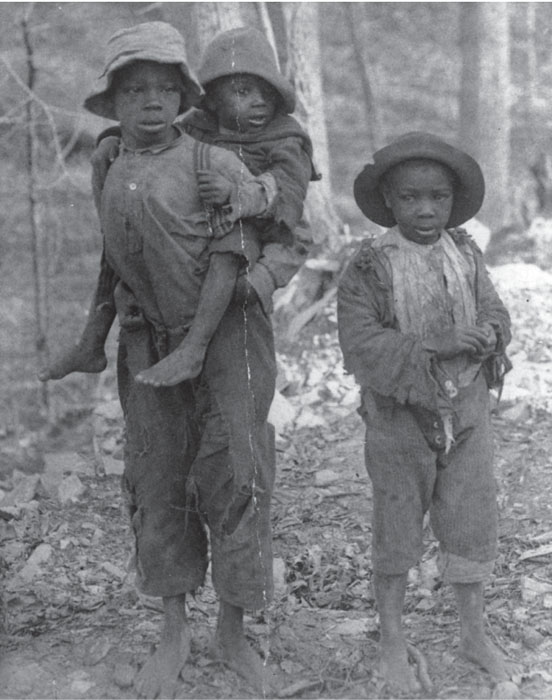

Stolen

Childhood

Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America

WILMA KING

SECOND EDITION

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404-3797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail iuporder@indiana.edu

First edition published 1995

2011 by Wilma King

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United

States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging

in-Publication Data

King, Wilma, [date]

Stolen childhood : slave youth in nineteenth-century America / Wilma King. 2nd ed.

p. cm. (Blacks in the diaspora)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-35562-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-22264-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. SlaveryUnited StatesHistory19th century. 2. Child slavesUnited StatesHistory19th century. 3. African American familiesHistory19th century. 4. SlavesEmancipationUnited States. 5. United StatesHistory19th century. I. Title.

E441.K59 2011

306.362083dc22

2010043634

1 2 3 4 5 16 15 14 13 12 11

To the memory of my father

and for his children, and their children

and their children, and

The slave population, as you remark, has had vast influence on the past, and may affect the future destinies of America, to an extent which human wisdom can neither foresee nor control.

Timothy Pickering to the Honorable John Marshall, January 17, 1826

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

During the intervening years since the publication of Stolen Childhood in 1995, an abundance of scholarship on slavery has appeared and enriched our knowledge about the institution of slavery across geographical regions and about enslaved children who came of age before 1865. For example, it is now known that the number of youthful Africans transported into the New World was greater than many had believed previously. In fact, the estimates range from one-fourth to one-third to the total. Moreover, a variety of sources, including Erik Hofstees dissertation The Great Divide: Aspects of the Social History of the Middle Passage in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database (CD-ROM), narratives by Middle Passage survivors, and the special edition of Slavery and Abolition 27 (August 2006), make data about enslaved children more readily available than ever before. As a result, this work devotes attention to the transatlantic trade in African children in the chapter titled In the Beginning: The Transatlantic Trade in Children of African Descent.

Another rationale for including a chapter about the transatlantic trade is the sheer number of children transported and the fact that youngsters were sought after by captains interested in filling their holds quickly with affordable chattel. And after the United States ended its participation in the overseas trade in Africans, an illegal trade continued and children remained a likely choice in the business of buying, transporting, and selling Africans.

The scope of Stolen Childhood has been increased in another way to include slave-born children in the North. The abolition of slavery in the

The changes in the geographical scope of this text make it possible to examine interactions between free, freed, and enslaved children across regions. In the process, it becomes clear that freeborn and emancipated persons were not entirely aloof from their enslaved contemporaries. In fact, few, if any, freeborn or freed persons in the North or South did not have a relative or friend who remained in bondage. This study looks at interactions between enslaved and free children as well as the extent of each groups knowledge about the existence of its counterpart.

This edition of Stolen Childhood attempts to move away from the notion that slavery was a southern plantation phenomenon in which white planters owned scores of black children and adults. To that end, it includes data about children owned by Native Americans and African Americans. The number of slaveholders of color and the size of their holdings were relatively small, yet they should not be dismissed. That Africans and African Americans owned other Africans or African Americans for economic and benevolent reasons is an integral part of this history.

Finally, the original study devoted little attention to childrens knowledge of or participation in the abolitionist movement. Since the time the first edition was published, the scholarship of Lois Brown has made the participation of children, witting or unwitting, in Susan Pauls abolitionist choirs impossible to ignore. Similarly, Molly Mitchells research highlighting free children in New Orleans provided data to show that teachers influenced their pupils thinking and sensitized them about the existence of slavery. The same can be said about schools for black children in New York and Cincinnati.

Aside from these additions, the intent and structure of Stolen Childhood remain unchanged.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and Historys 71st annual convention provided the first opportunity to discuss this work publicly; however, I canceled the October 18, 1986, presentation because of my fathers sudden death. It is ironic that the funeral services fell on the same afternoon of the scheduled presentation. Afterward, Sheila Miller, a librarian at East Pike Elementary School in Indiana, Pennsylvania, invited me to share my research with the sixth graders there. I protested, saying that I was not writing a book for children; rather, it was about children. Sheila insisted that the pupils would understand and appreciate my work. I agreed and was delighted to find the students at East Pike and subsequently at Eisenhower Elementary School, also in Indiana, Pennsylvania, truly interested in knowing about the lives of enslaved children in nineteenth-century America. They posed questions that only children of their ages could ask. Their inquiries were helpful.

I owe huge debts of gratitude to colleagues who kept an eye out for materials relevant to my research. Special thanks go to Darlene Clark Hine and David Barry Gaspar for their comments and encouragement in the early stages of research. Michael P. Johnson, Linda Reed, and Howard V. N. Young, Jr., provided beneficial comments after reading the entire manuscript. Robert L. Hall generously shared Prolegomena to a Social History of Slave Whippings in the United States, Jacqueline Goggin provided a chapter from her biography of Carter G. Woodson, and Lee Formwalt brought the Polly Ann Johnson case to my attention. My debts to these historians can never be repaid adequately. Other colleagues and friends shared research or provided pertinent references; my thanks to Edward Ayers; Richard Corby; Marcia Darling; Charlotte Fitzgerald; Beverly Guy-Sheftall; William H. Harris; Barbara Hill Hudson; Norrece T. Jones, Jr.; Irwin Marcus; Stanley Warren; and Hoda Zaki.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.