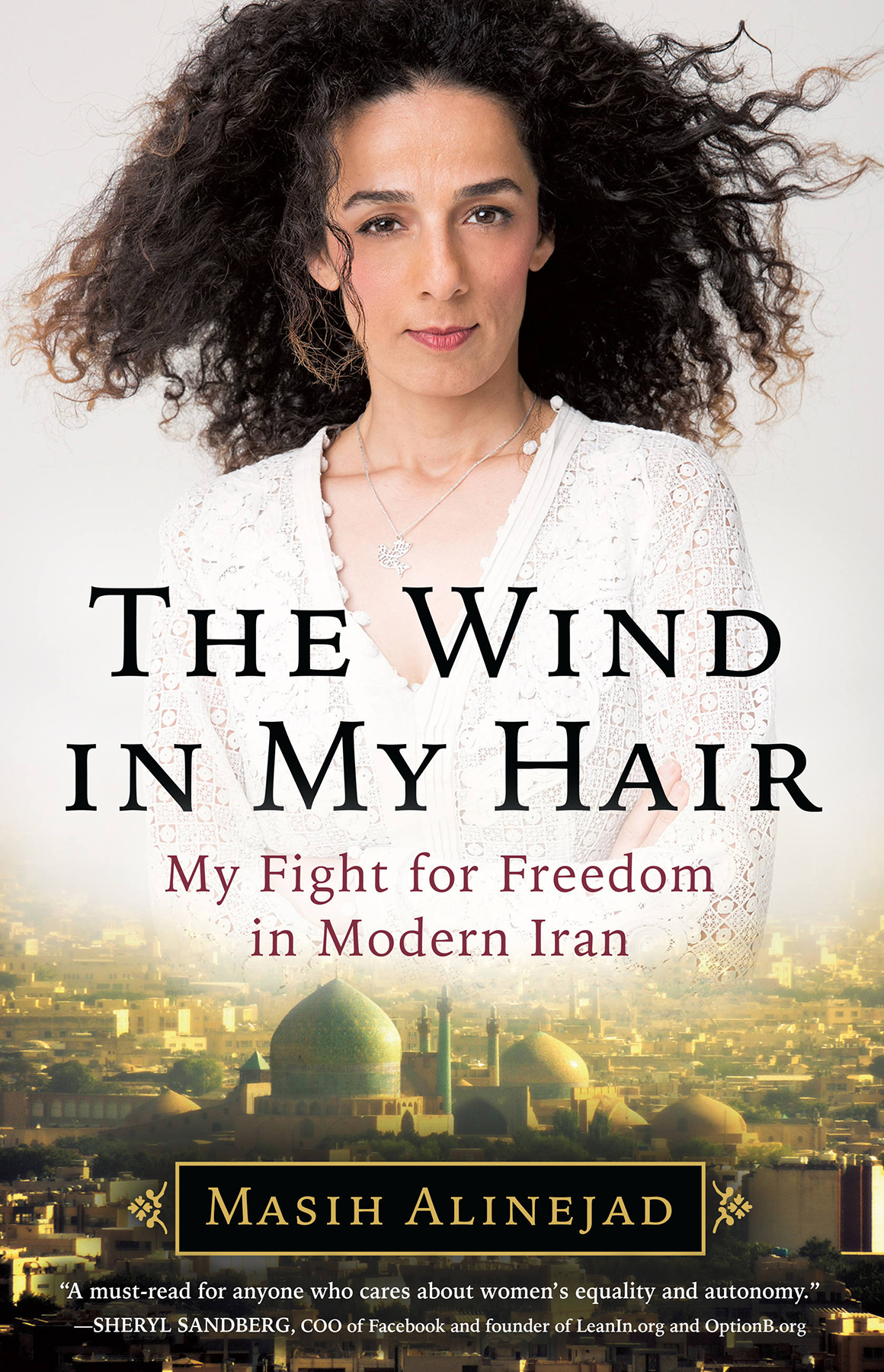

Copyright 2018 by Masih Alinejad

Cover design by Mario J. Pulice

Cover photographs by Deborah Feingold (author); Germn Vogel / Getty Images (cityscape)

Cover copyright 2018 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: May 2018

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-54907-3

LCCN 2017959142

E3-20200129-JV-PC-DPU

To the brave women of the My Stealthy Freedom and White Wednesdays campaigns

I t was pitch-black. Actually, blacker than black, if such a thing is possible. A blackness that extended forever and pulsed like a living being that could reach out and swallow you whole. On this warm summer night, it seemed as if even the moon and the stars had abandoned me. I stared into the night and the darkness stared back. If you let your fear win, the darkness can devour you, I told myself. Dont be afraid, I said quietly, over and over, like a mantra.

From behind me a faint sound of scraping and shuffling got louder and louder.

Wait.Wait for me, my brother Ali whispered as he caught up with me. I lost one of my slippers. His voice trailed off. Look, Ive brought the lantern.

I was tempted to say that I didnt need it. But the dim glow was comforting. I reached back and grabbed the lantern from Ali and lifted it high above my head so that there was a globe of light around us. Though Ali was two years older than me, right now I was in charge, because he was afraid of the dark. We started walking. The end of the backyard was still about fifty yards away.

Ten minutes earlier, I was with the rest of my familyMother and Father, my three brothers, and my sisterblissfully sleeping on the floor in the big room. Hard to believe but I was in the backyard because of Alis weak bladder. At thirteen, hed started wetting his bed. Its just a phase, I had overheard Mother explain to our father, or, as we called him, AghaJan, which means dear sir in Persian. AghaJan merely grunted, but I could see that he was troubled.

Sometimes Ali wet the bed in his sleep. Other times, hed wake up in the middle of the night with a great urge to pee, but we didnt have an indoor toilet, so he faced the long trek in the dark to the outhouse at the end of the backyard. He tried to steel himself to hang on till dawn, when there was enough light for him to feel brave. But no matter how much he tossed and turned, no matter how much he prayed to all the saints to give him endurance, he couldnt hold on. Ali was too old to be scared of the dark, AghaJan used to say, without too much sympathy. I was never afraid of the dark, and you can imagine how humiliating it was for Ali to wake me up so that I could walk with him to the outhouse. He didnt have to worry about waking our parents with his tossing and turning; AghaJan snoredthe noise was like the sound of the tractor that he used to till the land.

Wake up.I need to go.Wake up.Wake up.

I shrugged and rolled over, but he wasnt to be deterred.

Get up.I need to pee, Ali said with greater urgency, shaking my shoulder.

OkayokayIm awake, I said eventually.

A few weeks earlier, when he first started going through this phase, Ali was too embarrassed to wake me, and in the morning, there were the telltale signs. Hed rush outside as soon as he woke, but Mother discovered the wet stains when she rolled the bed up. Shed pretend that the wet patch and the stains were due to some household accident; often she blamed a leaking tea thermos, to save him from embarrassment.

Someone must have knocked over the thermos, shed say loudly, with a smile.

Who drinks tea in bed at night? Id ask mischievously. Isnt it strange how all the tea spills happen on his futon, Id say with a laugh.

Maybe he wanted to pay me back, because tonight Ali was determined to get me up.

Please, I need to go, he begged. Im getting desperate.

Okayokay, just hurry up, I mumbled as I rolled out of bed. I am having a good dream and want to get back to it.

In the backyard, even with a lantern in my hand, the distance to the outhouse looked pretty daunting. The warm air was dense with the summery whiff of crushed grass and a hint of burnt charcoal. Under the veranda, dozens of chickens were huddled, fast asleep. I wished I was back in my warm bed, but Alis eyes were fixed on the structure at the far end of the yard.

Lets go, I said wearily. I wanted to get back to my beautiful dream.

We shuffled forward sleepily.

During the daylight hours, Ali was like other teenagersfearless, boastful, and rebellious, part of a gang of boys who, when they tired of wrestling each other to the ground, took turns riding their rickety bicycles and then went for a swim in the Kolahrood (Kolah River). I used to think Ali was different. He read constantly, and he liked to recount stories in a colorful and dramatic style. But during the hot summer months I hardly saw him. From breakfast till dinner he was out and about, roaming the narrow dirt roads of our village. Hed come back dirty and stinking of sweat, his face red from hours of playing in the sun. Mother would drag him to the barn, where we kept our two cows, and would hose him down roughly with cold water before he was allowed inside the house. It was the same hose that she used to wash the cows.

Ali never took me with him no matter how much I begged him. I desperately wanted to run around the fields and ride a bicycle and jump in the river.

This was not possible, he said.

No girls are allowed. The other boys would laugh at me. He looked sheepish when he said this. Be reasonable. Even if I wanted to, AghaJan wouldnt allow it.

Its not allowed.

Its not permissible.

Girls cant do that.

I wasnt asking for much, but every time I wanted to do something that the boys were already doing, I heard the same refrain. I was eleven and I was tired of hearing it: You cant do that. Even now, the phrase You cant do that is like waving a red rag at a bull. It gets my blood boiling.

AghaJan expected girls to stay indoors and out of sight. He wasnt alone in his thinking. No other girls were allowed to run around and play outside the house. Boys had freedom and girls were kept indoors. It seemed so unfair.

Go on inside. Ill count to twenty and then Im heading back, I whispered to Ali as I yawned. If we dont hurry back Ill forget my dream.

Dont go, Ali said meekly. He took the lantern and gingerly opened the door to the outhouse, a narrow stand-alone room, as if half expecting a mouse or a snake to dart out. It was not unusual to find a grass snake inside, but as they were not poisonous I didnt mind them. Ali waved the lantern inside a few times before stepping in.