Praise for Iran Awakening:

'The riveting story of an amazing and very brave woman living through some quite turbulent times. And she emerges with head

unbowed' Archbishop Desmond Tutu

'One of the staunchest advocates for human rights in her country

and beyond, Ms Ebadi, herself a devout Muslim, represents

hope for many in Muslim societies that Islam and democracy

are indeed compatible' Azar Nafisi, author of

Reading Lolita in Tehran

A complex and moving portrait of a life lived in truth, as

Vaclav Havel would put it'

The New York Times Book Review

'With Islam as her starting point, Ebadi campaigns for peaceful

solutions to social problems, and promotes new thinking on

Islamic terms. She has displayed great personal courage'

The Times of India

An incredible memoir ... beautifully written. This is a book

infused with humanity and astounding hope'

The Works

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407028361

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Iran Awakening is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying

details have been changed, and conversations are, of necessity,

reconstructions based on the author's memory.

7 9 11 12 10 8

Published in 2006 by Rider, an imprint of Ebury Publishing

This edition published by Rider in 2007

First published by Random House, Random House, Inc.,

New York, in 2006

Ebury Publishing is a Random House Group company

Copyright 2006 by Shirin Ebadi

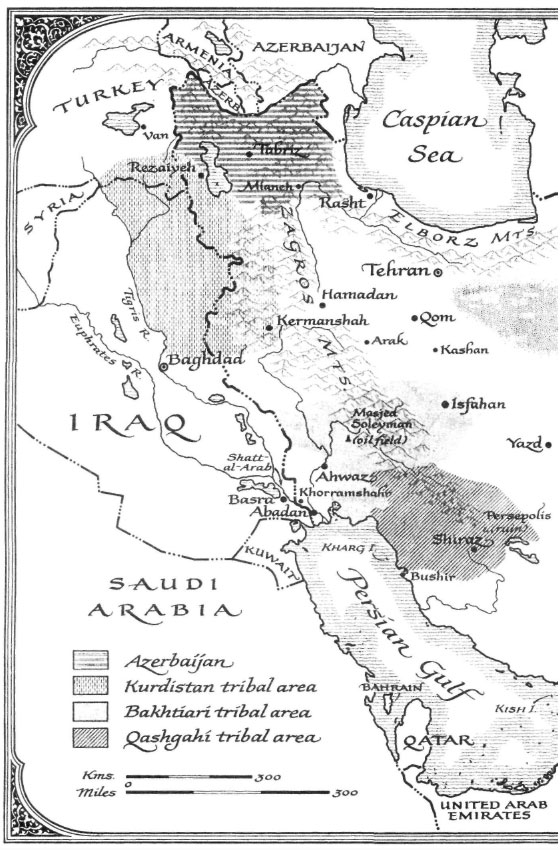

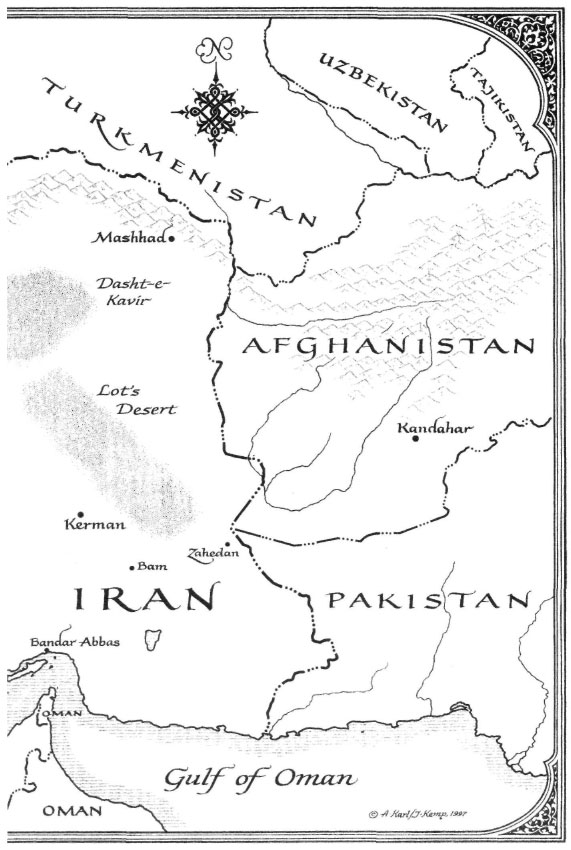

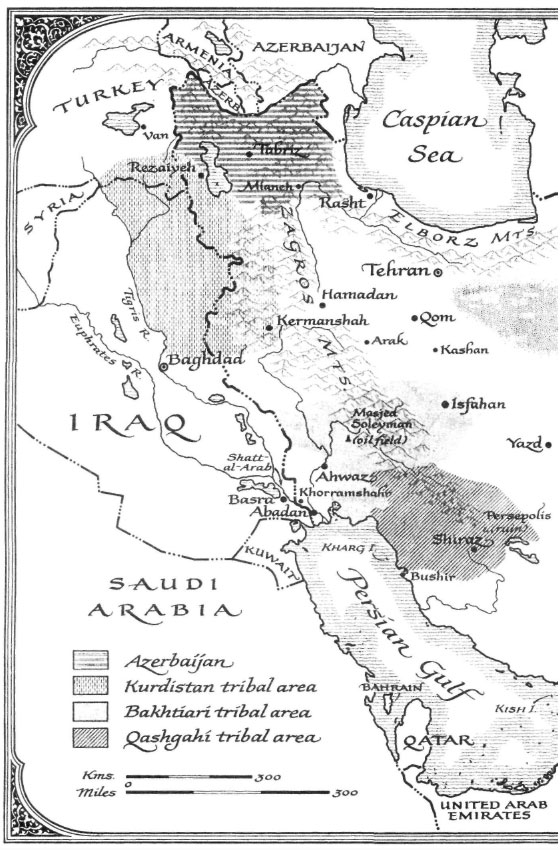

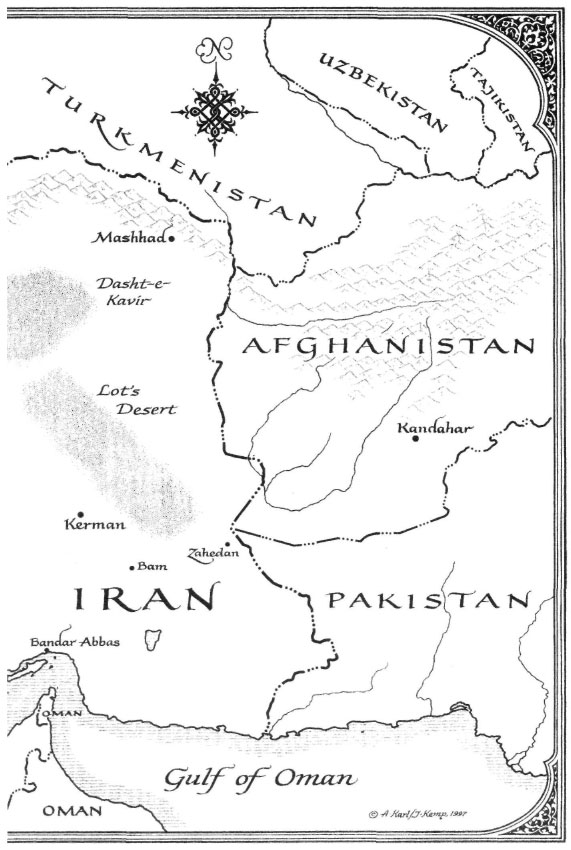

Map copyright 1997 by Anita Karl and Jim Kemp

Shirin Ebadi has asserted her right to be identified as the author of

this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988.

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.rbooks.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781407028361

Version 1.0

To buy books by your favourite authors and register for offers visit

www.rbooks.co.uk

In memory

of my mother and my older sister, Mina,

both of whom passed away

during the writing of this book.

Sadness to me is the happiest time,

When a shining city rises from the ruins of my drunken mind.

Those times when I'm silent and still as the earth,

The thunder of my roar is heard across the universe.

MOWLANA JALALEDDIN RUMI

*

I swear by the declining day, that perdition shall be the lot of

man. Except for those who have faith and do good works and

exhort each other to justice and fortitude.

THE HOLY KORAN 103:3

Prologue

IN THE FALL OF 2000, NEARLY A DECADE AFTER I BEGAN my legal practice defending victims of violence in the courts of Iran, I faced the ten most harrowing days of my entire career. The work I typically handled battered children, women hostage to abusive marriages, political prisonersbrought me into daily contact with human cruelty, but the case at hand involved menace of a different order. The government had recently admitted partial complicity in the premeditated spate of killings in the late nineties that took the lives of dozens of intellectuals. Some were strangled while out running errands, others hacked to death in their homes. I represented the family of two of the victims, and anxiously awaited seeing the files of the judiciary's investigation.

The presiding judge had granted the victims' lawyers only ten days to read the entire dossier. Those brief days would be our only access to the investigation's findings, our only chance to dig up evidence to build our case. The disarray of the investigation, the attempts to cover up the state's hand, and the mysterious prison suicide of a lead suspect compounded our difficulty in piecing together an account of what had truly transpired, from the fatwas ordering the killings to their execution. The stakes could not be higher. It was the first time in the history of the Islamic Republic that the state had acknowledged that it had murdered its critics, and the first time a trial would be convened to hold the perpetrators accountable. The government itself had admitted that a rogue squad within the Ministry of Intelligence was responsible for the killings, but the case had not yet gone to trial. When the time finally rolled around, we arrived at the courthouse, tense with determination.

After surveying the sheer physical volume of the files, stacks as tall as our heads, we realized that we would have to read them concurrently and, therefore, except for one of us, out of order. In deference, the other lawyers of the victims' families allowed me to start at the beginning, so each page I hurriedly turned, my eyes were the first to see.

The sun shone through the dirty windowpane, its rays moving across the room too quickly as we hunched shoulder to shoulder over the small table, silent save for the rustle of papers and the occasional thump of my wooden chair's stump leg. The significant passages in the files, the transcripts of the interrogations of the accused killers, were scattered throughout, buried in pages of bureaucratic filler. The material was dark with descriptions of the brutal murders, passages where a killer, with seeming relish, told of crying out "Ya Zahra," in dark homage to the Prophet Mohammed's daughter, with each stab. In the room next door, the defendants' lawyers sat reading other parts of the dossier, and it was impossible not to feel their presence radiating through the wall, these men who were defending those who had murdered in the name of God. Most of them were low-ranking functionaries of the Ministry of Intelligence, henchmen who had executed the death lists at the behest of more senior officials.

At around noon, our energy flagged, and one of the lawyers called to the young soldier in the hall to bring us some tea. The moment the tea tray arrived, we bent our heads down again. I had reached a page more detailed, and more narrative, than any previous section, and I slowed down to focus. It was the transcript of a conversation between a government minister and a member of the death squad. When my eyes first fell on the sentence that would haunt me for years to come, I thought I had misread. I blinked once, but it stared back at me from the page: "The next person to be killed is Shirin Ebadi." Me.

My throat went dry. I read the line over and over again, the printed words blurring before me. The only other woman in the room, Parastou Forouhar, whose parents had been the first to be killed, stabbed and viciously mutilated in their Tehran home in the middle of the night, sat next to me. I pressed her arm and nodded toward the page. She bent her veiled head close and scanned from the top. "Did you read it? Did you read it?" she kept whispering. We read on together, read of my would-be assassin going to the minister of intelligence, requesting permission to execute my killing. Not during the fasting month of Ramadan, the minister had replied, but anytime thereafter. But they don't fast anyway, the mercenary had argued; these people have divorced God. It was through this belief that the intellectuals, that I, had abandoned Godthat they justified the killings as religious duty. In the grisly terminology of those who interpret Islam violently, our blood was considered halal, its spilling permitted by God.