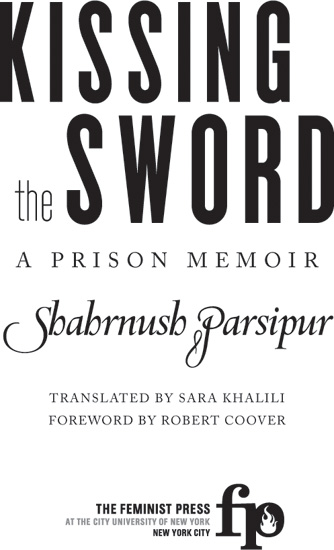

KISSING

the SWORD

Parsipurs memoir is a powerful tale of a writers struggle to survive the worst cases of atrocities and injustice with grace and compassion. A terribly dark but truly illuminating narrative; Parsipur forces the reader to question human nature and resilience.

Shirin Neshat

Kissing the Sword is a deeply moving, closely observed classic of its form... when they imprisoned Shahrnush Parsipur, they picked on one of the worlds greatest and most determined living authors.

Robert Coover, from the introduction

Published in 2013 by the Feminist Press

at the City University of New York

The Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5406

New York, NY 10016

feministpress.org

Translation copyright 2013 by Sara Khalili

All rights reserved.

Originally published in 1996 in Sweden as Prison Memoir by Baran Publishing.

No part of this book may be reproduced, used, or stored in any information retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

| This book is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. |

| This book was made possible thanks to a grant from New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. |

First printing March 2013

Cover design by Faith Hutchinson

Text design by Drew Stevens

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Parsipur, Shahrnush.

[Khatirat-i zindan. English]

Kissing the sword / Shahrnush Parsipur ; translated from the Persian by Sara Khalili.

pages cm

Originally published as: Khatirat-i zindan. Sp?nga, Sweden : Baran, 1996.

ISBN 978-1-55861-817-6

1. Parsipur, Shahrnush. 2. Authors, Iranian20th centuryBiography. 3. Political prisonersIranBiography. I. Title.

PK6561.P247Z46 2013

891'.558303dc23

[B]

2012043902

Contents

S AVAGERY IS A DEFINING CONDITION OF THE animal kingdom, but only humans, blessed with reason, can invent death camps, inquisitions, the subtle instrumentation of torture, mass executions. We continually amaze ourselves with viciousness, the cause of which is less often bloodlust or brutality than it is mere expediency. Certain persons threaten our authority and well-being, and the easiest and most effective means to get them out of the way is to exterminate them. For protesting the execution of two leftist poets, Shahrnush Parsipur was imprisoned the first time and sentenced to two months in solitary confinement by the shah of Iran, a cruel and ruthless man who used his CIA-created secret police, SAVAK, to do his dirty work; but when the citizens grew restless, he resisted US iron fist advice, proving to them his essential weakness, and in 1979 his regime fell to the powers who control this narrative. The ayatollah and his revolutionary guards had more backbone. Within a short time, they had rounded up not only the royalists, but also their revolutions former allies, the secular leftists and the Islamist-Marxist Mujahedin, and the slaughter began, the success of which is evidenced by the regimes continuance (and continued political executions) to this day.

The surviving witnesses of such mass killings are often silenced by fear or oppression, or worse, a broken spirit. Not so the gifted and resilient author of this harrowing memoir, imprisoned three times by the Islamic Republic of Iran, the first time for four and a half punishing years, eventually driven into exile by the threat of further arrests and harassment, her health by then seriously damaged, her writings banned, her pockets empty, but ever keeping faith with her chosen vocation as a writer and unbending witness to her times. Kissing the Sword is a deeply moving, closely observed classic of its form, and would be viewed as such, no matter who its author, but when they imprisoned Shahrnush Parsipur, they picked on one of the worlds greatest and most determined living authors. Indeed, the first draft of Touba and the Meaning of Night, an epic masterpiece in the same league with One Hundred Years of Solitude and Midnights Children, was scribbled into notebooks, as readers will discover here, during the terrible ordeal of her long imprisonment. She is the author of nearly a dozen other works of fiction, written before and after that time, most famously perhaps Women Without Men, made into an award-winning film by the video installation artist Shirin Neshat.

Kissing the Sword is a searing depiction, with very little self-pity or moralizing, of a living nightmare. It quietly celebrates, amid unspeakable horrors, such virtues as decency, integrity, thoughtfulness, concern for othersthese being other inventions of the human animal. And honesty: nothing goes unsaid. The narrative often shocks, sometimes touches, almost always dismays, its most appalling discovery perhaps being that, upon release from prisons cruel theater, the nightmare does not end. It is only less structured.

Robert Coover

Los Angeles, December 21, 1995

I T IS THE FIRST DAY OF WINTER. THE SUN RISES.

I bow down in prayer. I believe that all existence is conscious. I believe that every speck of dust somehowdust likeis conscious. I believe that you cannot find two hydrogen atoms that are identical. I believe that hydrogen atoms, too, are somehow conscious. And so, I pray:

God, I praise you in all your manifestations. This is you burning yourself in one scene so as to come forth in others. This is you who at times wish not to be, so that all at once you can overwhelmingly be. This is you who wished that I witness your death and rebirth in a sea of blood. Give me the power to write that which I have seen in prison.

Work is always a savior and my work is to write. I have lived through difficult years and in the past two, I have been suffering from a severe nervous disorder. A vague pain creeps up my vertebrae and into my brain. I tell myself, Time is short, if you dont write now you may never have another chance. I think of the millions of books gathering dust in huge libraries. Amid all these, what value could my work really have? Yet, this is the only thing I know how to do. I tell myself, Write! Dont worry that it may not be read. It is the age of the computer and every day people in the advanced world grow more distant from the old world, every day a new discovery is tested and professors in their great rush cannot write their books and instead hand them to their students as notes. But, dont worry, write. Perhaps someone will read it.

One day in the communal cellblock at Ghezel-Hessar Prison, at the time of evening prayers, which coincided with the television news hour, we learned that an American space shuttle with seven crewmembers onboard had exploded. They showed footage of the explosion. As always, when important news was being broadcast, there was a great commotion. The prisoners all ran toward the television and the details of the news were lost in the noise. This always upset me. Television was our only window to the world, and even I who didnt have a natural affinity for it, had come to depend on it. On another occasion, when I was in Disciplinary Unit 8, the news story being broadcast was about the leader of one of the leftist groups whose members were being persecuted by the government. Obviously, the prisoners who were supporters of that party were quite interested, but again, much of the information was lost in the clamor of people jostling for a place in front of the television. That time, I suddenly screamed, Shut up! A strange silence fell across the unit and we managed to hear the tail end of the story. People who know the etiquette of dancing always know when to be still, when to move, and when to be silent. But unfortunately, dancing is considered shameful in present-day Iran.