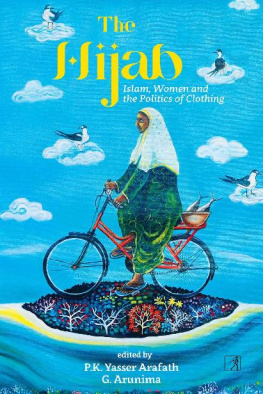

The Hijab

The Hijab

Islam, Women and the

Politics of Clothing

Edited by

P.K. YASSER ARAFATH

G. ARUNIMA

Our inspiration: the Muslim girls and women protesting for their rights in India and Iran. This book is dedicated to them.

INTRODUCTION

BANNING THE HIJAB

Politics and Perspectives

P.K. Yasser Arafath and G. Arunima

Its only very recently that wearing the hijab has become controversial in India. While at the moment this is restricted to some educational institutions, mainly schools and pre-university colleges, the fallout of this can be far reaching. While much of the discussions of the hijab ban in India has centred on whether wearing the hijab to school violates the dress code, and the impact of the ban on their education, in other parts of the world where similar bans were invoked earlier, like France, the debates focus has been on a reappraisal of secularism.

The trigger for the ban on wearing the hijab started with a government run pre-university college in the southern Indian state of Karnataka disallowing Muslim girls from wearing it. The grounds were that it violated the uniform or the prescribed dress code in their college. This decision by the school authorities was met with protests by school and pre-university girl students, and those organized by Muslim organisations like the Campus Front of India, without much luck, resulting in their turning to the courts with the hope of a possible reversal of the ban. The Karnataka High Court however upheld the right of the schools to endorse the state governments ban, refuting all the main grounds that had been raised by the students. These included arguing for the right to freedom of conscience (Article 25 in the Indian Constitution) and the right to freedom of expression and privacy. While the legal turn in this instance has meant that the terms of reference for the question of Muslim girls right to wear the hijab to school is now determined by law, the ban and the Karnataka High Court verdict forefronts several issues including the meaning of secularism in such an instance, the rights of Muslim women over their bodies and beliefs, and ways of understanding the hijab itself.

Since hijab banning isnt unique to India, and has provoked intense debates and discussions in many parts of the West, it is useful to engage some of the main issues raised in those contexts. In one of the most significant discussions on this issue, feminist historian of France Joan Scott in her work, Politics of the Veil , asks why the headscarf became intolerable and controversial in France? This is then absorbed quite seamlessly into a narrative about gender equality and its absence in Islam.

In her later work, a wide ranging meditation on the theme of secularism in the west, including its many meanings, Joan Scott unpacks these histories to point out that gender equality wasnt intrinsic to secularism as is assumed at present. The relegation of religion to the private sphere, along with women, home, family and affective relationships was to set it aside from the real world of menstate, markets and politics. In fact, as she shows, the only time that French politicians (men) begin to espouse ideas about gender equality is well into the 20th century, and this was mainly in order to contrast French secularism with Islam.

While Joan Scotts argument is a detailed historical exposition of the meanings, and limitations, of secularism she is not alone in critiquing the idea of the secular. Political anthropologist Saba Mahmoods critique of secularism in this context has been powerful and influential. She explores the contradictions of secularism further when she poses the question of whether the principle of freedom to practice religion was integral to liberal democracies.

What is distinctive about the Indian case is that secularism here does not simply mean a separation of religion and state or a removal of the former from public life. While constitutional provisions that define Indian secularism assert that India will not have a state religion, provide religious instruction in schools, or support any religion through state taxes, the right to religion too is protected by the Constitution, including the right to believe, practice and propagate it. In other words, in India religion is not relegated to the private sphere. That said, as Partha Chatterjee demonstrates the state has become entangled in the affairs of religion in numerous ways, This entanglement aside, in India one also needs to examine the historical creation of personal laws. These laws were a colonial invention that clubbed together matters pertaining to family, marriage, property and inheritance together, terming these as personal, and making these subject to religious laws and interpretation. While a detailed discussion of the history of evolution or transformation of personal laws isnt within the purview of this volume, suffice it to say here that the colonial administration, in its bid to appear non-invasive, relegated personal laws to the realm of religion. This meant that all matters pertaining to those areas defined as personal were now to be determined by taking recourse to religious texts, and authority. While this did not result in an instantaneous transformation of these matters, in many cases older, more flexible, customary practices were eroded after having been brought within the ambit of religiously inspired legal interpretation. That said, it is worth mentioning that in the postcolonial context, constitutionally defined Indian secularism permits several different kinds of personal laws, and customary practices, to co-exist with civil and criminal laws of the country. Personal here is religious, and not private or feminized as has been the case in France; it is precisely this that guarantees personal laws some protection from state interference. Therefore, despite the ambiguous status of many of these personal laws, the general understanding is that communities should be left to reform, or jettison, any or all of these. This also means that any practice that can be seen as coming under the jurisdiction of personal laws can continue undisturbed until these are challenged by members of the community itself. However, in more recent times in India, we see that this is not necessarily the case and there are attempts to erode the status of personal laws, particularly those based on Islamic jurisprudence.

It is clear from the above discussion that Mahmoods important argument, centred as it is on the French model of secularism and post 9/11 discussions regarding Islam in the US, cannot be applied without qualifications, for an understanding of Indian secularism and its crisis. Indeed the distinction that womens and religious studies scholar Leila Ahmed makes, between lay and establishment Islam may be more helpful for an understanding of religion per se. She argues that while there is an ethical impulse in a lay understanding of Islam, establishment Islam is far more invested in political power, and therefore wishes to eliminate those who challenge its authority. This, if transposed to the Indian context, could be said to be true of Hinduism too, where historically popular practices have been ethical, and egalitarian, in spirit (for instance bhakti, or the many subaltern faith practices that have proliferated in the country) whereas establishment Hinduism (like Hindutva) is entrenched in political power. Ahmeds was amongst the earliest discussions that located the idea of womens oppression in Islamic societies within a colonial, and racist, discourse inaugurated by the Victorians. As she demonstrates colonizers, despite dismissing feminisms claims locally, utilized its language within their colonial project. She shows the shifts in attitudes regarding education, marriage, family and dress amongst Egyptian women over a century long period, and argues against the simplistic correlation equating forms of dressing in Muslim majority countries with womens oppression. On the contrary, she shows the many reasons for its adoption in the context of the 20th century, including the practical solutions and ease it provides for women, often from rural or lower middle class families, for seeking education, mobility, employment and even the desire to fraternize with men.