ESSAYS BY

Negla Abdalla

Zahra Adams

Fatima Ahdash

Sabeena Akhtar

Mariam Ansar

Shaista Aziz

Suma Din

Khadijah Elshayyal

Ruqaiya Haris

Fatha Hassan

Raisa Hassan

Sumaya Kassim

Rumana Lasker Dawood

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan

Asha Mohamed

Sofia Rehman

Yvonne Ridley

Aisha Rimi

Khadijah Rotimi

Sophie Williams

Hodan Yusuf

With special thanks to the patrons of this book

Jannatul Shammi

Tilted Axis Press

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Let me begin as Muslims often do: with thanks. Thanks to Allah, the most merciful, most high, without whom we would be nothing.

Thanks to Unbound for providing us with the space to share our words, and to you, the reader, for your ongoing support. Thanks to my Muslim sisters, in all our struggles, joy and configurations this book is for you.

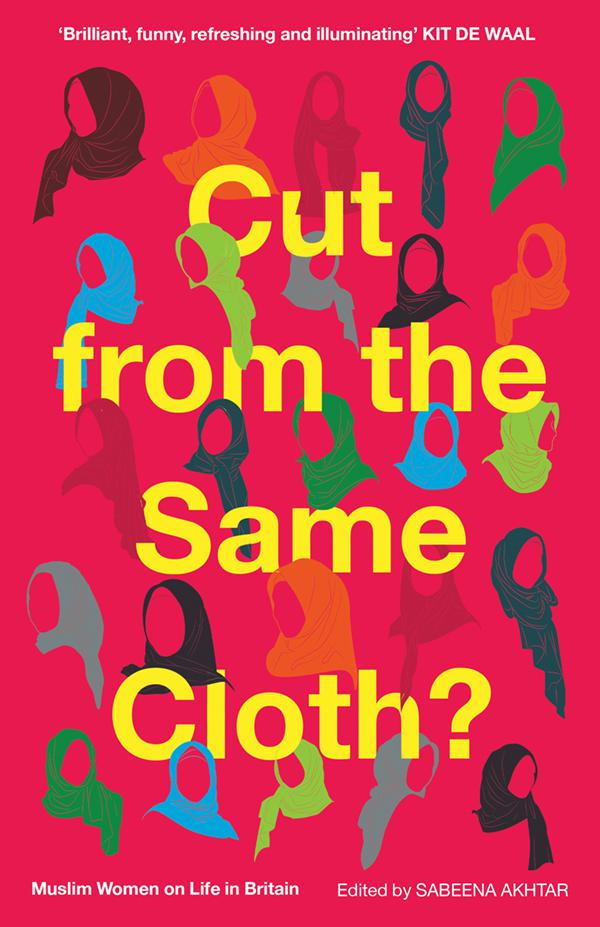

When Unbound invited me to work on an anthology by visibly Muslim women, I jumped at the chance. Like so many Muslim women I had sat on the sidelines time and time again, growing frustrated with negative portrayals and tired stereotypes. While Muslimness is, of course, not limited to a piece of cloth, so often we as hijab-wearing women find ourselves judged by our visibility without being afforded ownership of the narrative that surrounds it. I sometimes think of the hijab as a mirror. What is projected onto it is often a reflection of a persons own character, politics and baggage, it is seldom about the woman underneath. Even in the midst of the global pandemic, we find that (unrelated) images of women in hijabs have become weaponised, accompanying many of the negative COVID-19 news stories in order to further malign communities that are already disproportionately suffering at its hands.

The effect of wide-scale securitisation, hostility and sur-veillance of the Muslim community has also increasingly manifested itself in the palpable othering of hijab-wearing women, who are perceived as the visual representatives of Islam. What we are reduced to are the passive enablers of violent Muslim men or the radical Other, and, in the case of Shamima Begum, both. She is presented in her black khimar devoid of context, stripped of citizenship, due legal process and even humanity. She has not been radicalised, she is radical. Her predisposition to violence is read as innate. Yet, despite all of this co-opting and projecting onto the hijab, as visibly Muslim women we are rarely afforded an opportunity to discuss our experiences on our own terms and, crucially, through the prism of our spirituality. In books and in the media we are spoken on behalf of, often, by men, non-hijab wearing women and non-Muslims. Too often we are seen to exist only in statistics, while others gain a platform off the back of the hostilities we face. Yet it can sometimes feel as if we are inundated with endless op-eds, behind the veils and thinkpieces about hijab and Muslim women. I invite readers to ask why this is, what the purpose behind the pieces is, what their appeal is and, most importantly, who are they written for? As my dear friend and contributor Sumaya Kassim pointed out in an update for this project, often, it feels like Muslim women are only valuable when theyre selling something, or when theyre oppressed/silenced. As silent, invisible beings, Muslim women serve specific political purposes: we make mainstream feminists feel good about being liberated, we make secular liberals feel progressive, we provide anti-Islamic media outlets and YouTubers with plenty of revenue, and an excellent excuse for the government to commit all manner of crimes in the name of saving us. But what of our own stories, religiosity, hopes and creativity? I wanted to create a space for visibly Muslim women to speak freely about their lives and interests without being reduced to passive inhabitants in them, and not because we have something to prove or disprove, but simply because . Perhaps naively, I did not anticipate how political a collection of personal essays written by visibly Muslim women would be.

The path to publication of this anthology has not always been easy. Along the way we have been told by some claiming to be feminists that as women who are visibly Muslim or have had the experience of being visibly Muslim, we are oppressed and should hence be no-platformed. They would rather shut down the voices of some women than engage with that which contradicts their own preconceived colonial values. Such is the twisted logic of some corners of liberalist thought. Weve been accused of being everything from the ominous traditionalists with agendas to rabid feminists, social-justice warriors and, more recently, critical race theorists (apparently a slur) simply because we wanted to write a book. As many random strangers have hypothesised about what lies within these pages, perhaps we should begin with what this is not. It is not a polemic on the hijab and why we wear it, or a litmus test of our relatability to the white gaze. It is not a group of hijab-wearing women looking down on the women who dont wear it. Its a hijab, not a halo. Our experiences do not negate or take precedence over any other.

There will be no grand unveilings, and we will not be making or breaking any stereotypes today; nor will there be any justification or condemnation of our various religious standpoints. This book is not a pulpit or minbar, it is not data for analysis, it is not an opportunity for voyeurism and it is certainly not a government-funded initiative. It is but a small snapshot of the many and varied lives, concerns and issues important to women across race and class who have simply had the shared experience of being visibly Muslim in Britain today. Though we cover a broad range of topics, many of the pieces deal with how we, at the various intersections of our identities as Muslim women and girls, are perceived and taught to perceive ourselves, and how we can recognise and resist the distorted lens through which we are regarded. Asha examines how the education system embeds racial hierarchy at a young age, while Negla reflects on how we internalise inferiority and the impact that has on Black Muslim women in particular. Hodan expands on how Black Muslimahs are often unsafe both outside and within the Muslim community, and Sumaya, Rumana, Ruqaiya, Khadijah R. and Raisa discuss how stereotypes, social media, beauty standards, ableism and racial perceptions taint the relationships we have with ourselves and our creative output. Mariam, Aisha, Suma, Khadijah E. and Fatha explore our relationships with physical spaces, place, motherhood, COVID-19 and men. Fatima laments the treatment of Arab Muslims in the human-rights sector, and Yvonne, Sophie and I discuss the political and mental impact of hypervisibility and invisibility, the starkest example of which can be seen through Zahra and Shaistas piece on Grenfell. Suhaiymah reaches the conclusion that the questions put to us as Muslim women are themselves an exertion of power that control the narrative, irrespective of the answer, while Sofia engages scholarship and the Quran as praxis for understanding what she calls the triple consciousness of being Muslim, British and woman.

While we differ in our understanding and approaches to the many perceptions of Muslim women, all of us in the various stages of our journeys find solace and liberation in the submission to Allah. As a writer I have experienced first-hand the appetite for stories by Muslim women that fit a reductive blueprint, ironically often centring Muslim men and our reactions to their perceived oppressions, or measuring our worth or relatability through capitalism or secularism preferably devoid of any spirituality, despite this being a religious identity. Diversity among Muslim women is often presented as falling within the binary of extremist versus culturally Muslim. I wanted to scratch beneath the headline-grabbing dichotomies and hear from women like me, who are often overlooked or tokenised in our own stories by audiences that prefer women who are more relatable to Western hegemonies, who are able to dismiss or fulfil stereotypes about who it is thought we are: oppressed or radical, passive or pint-drinking, religious or liberated, boring or skateboarding.