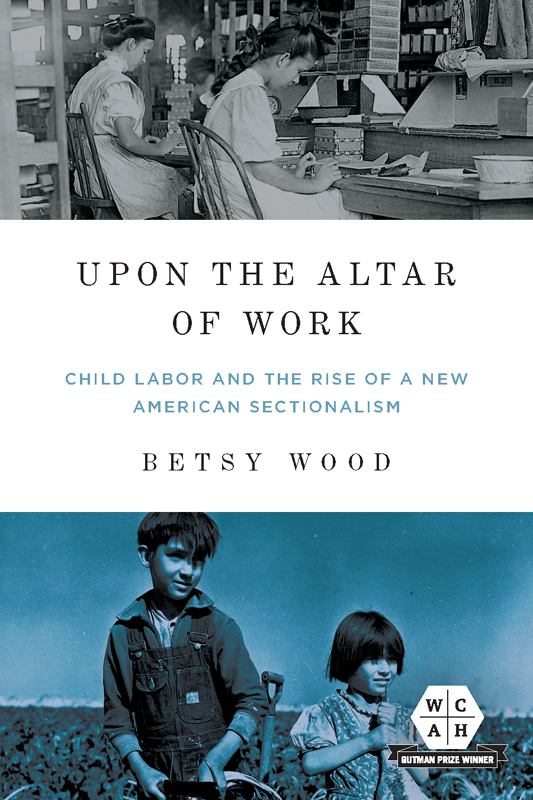

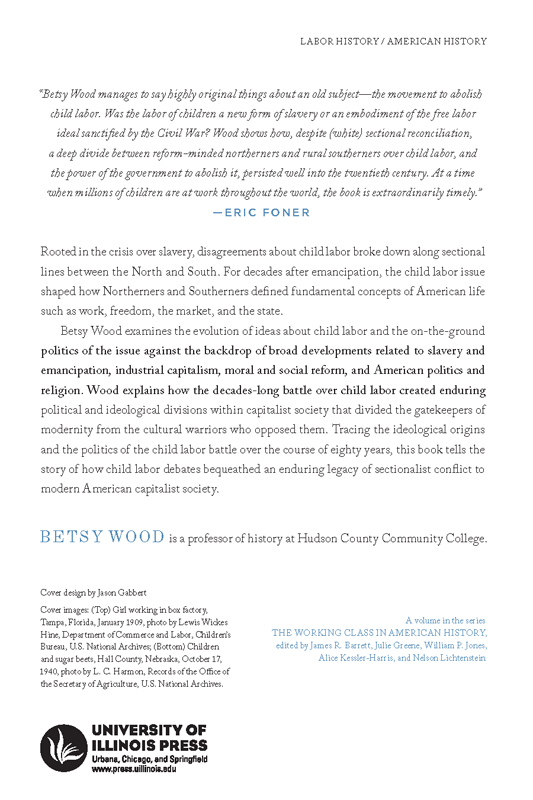

UPON THE ALTAR

OF WORK

CHILD LABOR AND THE RISE OF A NEW

AMERICAN SECTIONALISM

BETSY WOOD

UPON THE ALTAR

OF WORK

Contents

2020 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wood, Betsy, author.

Title: Upon the altar of work : child labor and the rise of a new American sectionalism / Betsy Wood.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, [2020] | Series: The working class in American history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020006470 (print) | LCCN 2020006471 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252043444 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252085345 (paperback ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252052323 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Child laborPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | Sectionalism (United States)History.

Classification: LCC HD 6250. U 3 W 66 2020 (print) | LCC HD 6250. U 3 (ebook) | DDC 331.3/10973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020006470

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020006471

For Andrew and Julian

THE WORKING CLASS IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Editorial Advisors

James R. Barrett, Julie Greene, William P. Jones,

Alice Kessler-Harris, and Nelson Lichtenstein

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

UPON THE ALTAR

OF WORK

Fields of Free Labor

Child Rescue and Sectional Crisis

Let him that stole steal no more:

but rather let him labour,

working with his hands the

thing which is good.

Ephesians 4:28

On the eve of the American Civil War, a white, orphaned fourteen-year-old boy named John showed up at the Childrens Aid Society in New York City. Years earlier, John had been picked up by police officers and taken to the House of Refuge, an institution for poor children that bound out John and another white, orphaned boy named Henry to a slaveholder in Delaware in an effort to reform them. When the staff of the Childrens Aid Society (CAS) greeted John, he told them about his experiences on the Delaware plantation. John and Henry had tried to be honest and to work as well as we could, but it was challenging since they were not treated right. The CAS staffer who recorded the story wrote that the boys never had a chance to improvethough the slaveholder pretended the boys were doing well when a superintendent from the House of Refuge visited to inquire about them. When John decided he would rather quit than be bound to such a man, Henry was afraid that John would be killed by the savage man, our master. The two boys, along with one of the colored boys from the plantation named Robert Wilson, who had been nearly killed with lickings, decided to run away together.

The Delaware slaveholder found the boys and beat them as punishment for running away. Five times after this I ran away, and four times I was catched [ sic ] and brought back, John said. After he had been on the plantation for four years, John made up his mind to run off again, to escape another flaying.

In the 1850s, at the height of sectional tension over slavery in the South and its spread into territories in the West, debates about how to rescue poor children in the capitalist North shaped the way antebellum Americans articulated distinctions between free and slave society. Through the rescue of poor urban children in the Northespecially boys, who were expected to become independent laborers and heads of household within free societychild reformers praised the virtues of Northern free society while condemning the evils of Southern slavery. When the Childrens Aid Society designed a plan to send poor, orphaned Northern boys like John to work on farms in the West, they were joining a national debate about the fate of the West as either slave or free. Unlike juvenile asylums and other penal institutions that aided poor children, the Childrens Aid Society developed an approach to child rescue in response to the sectional conflict over slavery. These free labor ideals shaped the work of the Childrens Aid Society. In turn, the CAS shaped free labor ideals by applying them to Northern child rescue and promoting their tangible effects upon poor Northern children.

Childrens Aid Society reformers thought they could end Northern child poverty by sending poor orphaned boys to farms in the West where they would become free laborers. The prospect of settling the West with boys who had been rescued from what reformers called a life of vagrancy in the city became one of the CASs primary goals in the 1850s. In their view, this plan would not only help to rid the city of a labor surplus while supplying Western farms with laborers, but it would also demonstrate the superiority of Northern free society. The expectation was that through free labor, boys like John could learn values of free society such as discipline, honesty, and frugality that were thought to produce socially mobile, independent male citizens. This expectation was in contrast to enslaved labor, which was supposed to produce fixed hierarchies rather than social mobility and was believed to promote idleness, dishonesty, and wastefulness. On the Delaware plantation, according to the CASs retelling, John was subjected to a system of enslaved labor in which he did not benefit or learn from his labor. In a nation on the verge of civil war, child rescue in the North helped to shape the meaning of free labor as chattel slaverys opposite. Through debates about poor Northern children, the CAS inveighed against the evils of chattel slavery while lauding the virtues of free society. In comparison to adults, childrens malleability made them a powerful tool for sharpening and testing free labor ideals in a nation torn apart by the slavery dispute.

Shaping the work of the Childrens Aid Society was a commitment to a producer ethic grounded in free labor Republicanism. This ethic valorized the independence of property-owning male producers as the objective of dignified labor. According to this ethic, both permanent wage status and permanent pauperism signaled dependency, which was thought to be the antithesis of free labor.

In the 1850s the Southern way of life emerged as a violation of free labors most cherished principles. Not only was labor unfree in the South, the argument went, but it was also disparaged as the fate of enslaved persons. For free labor Republicans, contempt for labor had produced Southern values of indolence and disorder, leading to the regions stagnation.

The Childrens Aid Societys approach to rescuing poor Northern children turned on deeply held views about the purpose of labor. Honest work, the CAS argued, had the ability to teach Northern urban boys how to be independent and free. In its First Annual Report , the Childrens Aid Society discussed in some detail the unhealthy relationship to labor that poor Northern children had developed. The CAS sought to engineer social mobility in the lives of boys for whom mobility was difficult, since their circumstances prevented them from learning industrious values or benefiting from their labor. In this inaugural report laying the groundwork for their agenda, the organization articulated a profree labor program emphasizing Northern urban boys proper relationship to healthy and honest labor. This free labor ideology relied on the presence of slavery in the South for coherence and was intended to strengthen the moral legitimacy of industrial capitalism and superiority of Northern free society.